Many years ago my wife and I were confined by the police to our hot hotel in Rhodes for an evening, a fate we shared with other tourists as a result of anticipated demonstrations against the appearance of a Turkish ship in the harbour. It was another time of strained relations between Greeks and Turks. Up in our room, I decided it was time I asserted myself as a war correspondent. Out on the balcony with notepad and pen, I could hear the anger and the pounding feet below. I began to scribble – then heard the launching of canisters, smelled the tear gas and nimbly stepped back into our room, all my bravado gone. I picked up the Hemingway I had been reading and poured myself another glass of retsina. He can take you that way.

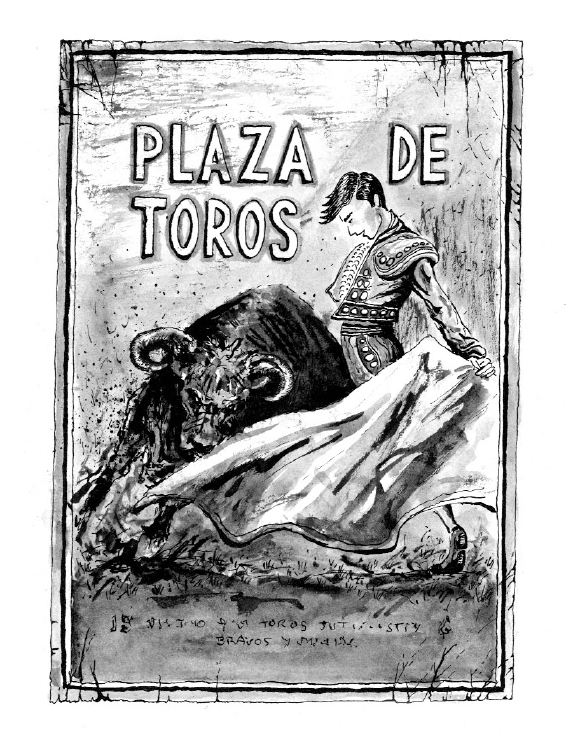

Now, thirty years later, I have just reread Ernest Hemingway’s first and best novel, The Sun also Rises, written when he and the century were 26 years old. It is a roman à clef, dispensing justice and injustice to members of the Parisian circle surrounding Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley. One of the novel’s epigraphs is the now famous remark Gertrude Stein seized upon, ‘You are all a lost generation.’ In fact, ‘wasted’ might be a better adjective to describe a novel in which a bunch of literary drunks gather round a nymphomaniac at Parisian café tables, before taking off for the Spanish bullfights in Pamplona, where each earns his horns. Yet what I loved about the novel – and, with a little more tolerance for human weakness produced by the passing years, still do – is its mixture of post-war pessimism and gaiety, fuelled by constant drinking and banter.

First though, with Hemingway there is always the man to get past in order to see the print up close, a man whose life was made up of large appetites and a shoal of little fictions. Hemingway (1899–1961) came out of a Chicago suburb and, imaginatively, the woods of northern Michigan. After serving as an ambulance driver in the First World Wa

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inMany years ago my wife and I were confined by the police to our hot hotel in Rhodes for an evening, a fate we shared with other tourists as a result of anticipated demonstrations against the appearance of a Turkish ship in the harbour. It was another time of strained relations between Greeks and Turks. Up in our room, I decided it was time I asserted myself as a war correspondent. Out on the balcony with notepad and pen, I could hear the anger and the pounding feet below. I began to scribble – then heard the launching of canisters, smelled the tear gas and nimbly stepped back into our room, all my bravado gone. I picked up the Hemingway I had been reading and poured myself another glass of retsina. He can take you that way.

Now, thirty years later, I have just reread Ernest Hemingway’s first and best novel, The Sun also Rises, written when he and the century were 26 years old. It is a roman à clef, dispensing justice and injustice to members of the Parisian circle surrounding Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley. One of the novel’s epigraphs is the now famous remark Gertrude Stein seized upon, ‘You are all a lost generation.’ In fact, ‘wasted’ might be a better adjective to describe a novel in which a bunch of literary drunks gather round a nymphomaniac at Parisian café tables, before taking off for the Spanish bullfights in Pamplona, where each earns his horns. Yet what I loved about the novel – and, with a little more tolerance for human weakness produced by the passing years, still do – is its mixture of post-war pessimism and gaiety, fuelled by constant drinking and banter. First though, with Hemingway there is always the man to get past in order to see the print up close, a man whose life was made up of large appetites and a shoal of little fictions. Hemingway (1899–1961) came out of a Chicago suburb and, imaginatively, the woods of northern Michigan. After serving as an ambulance driver in the First World War on the Italian front, where he was wounded, he became a newspaper man in Paris, then a stylistically innovative author. Later incarnations included war correspondent, big-game hunter, deep-sea fisherman and world-class celebrity. He left behind him bestsellers, a Nobel Prize, four marriages and their resulting children. There is an enormous difference between the uncomplicated Hemingway heroes and the man himself, whose turbulent life ended in suicide at the age of 62. Like John Wayne, in the popular imagination Hemingway increasingly became his code, though its macho element does not always sit well with today’s attitudes. (There is a highly entertaining parody of the man and his famous ‘grace under pressure’ in Woody Allen’s film Midnight in Paris.) The idea of Paris in the 1920s is formidably attractive to the romantic sensibility. For American bohemians of the day it offered artistic licence, sexual freedom, the absence of Prohibition and an admirable exchange rate – so much so that by 1924 thirty thousand Americans were living there permanently. Hemingway was one of the early beneficiaries, writing for the Toronto Star and living on his earnings and his wife’s trust fund. His prose captured the character of the left bank’s Latin Quarter. ‘The Dôme’, ‘The Select’, ‘The Rotonde’ were in full swing – cafés with their zinc bars, the little saucers piling up after each Pernod, the artists and their models, the poules, the bal-musette music, the bateaux mouches on the Seine. The greater part of The Sun also Rises, however, takes place in Spain, where the characters attend the San Fermin bullfighting festival in Pamplona, at the foot of the Pyrenees. Events are spun from the misadventures of the Hemingways and their friends on a trip in June 1925. The narrator Jake Barnes (unlike the author) is fluent in French and Spanish, which leads to innumerable incidental encounters that add flavour to the book. At the Spanish frontier, for example, Jake talks to a carabineer about a man refused passage:Their trip begins peacefully enough, with Jake and his writer friend Bill Gorton fishing in northern Spain. On the way we meet Hemingway’s peasants: noble, curious and bibulous figures, eager to share their wineskins. They have the simple dignity Hemingway afforded his working men. He has a wonderful ear for their dialogue, with its quiet, courtly humour. Later things get rowdier, when the rest of the gang descend on Pamplona and its bulls. Oddly, given that the novel’s central character is a newspaperman in this turbulent post-war period, we have no sense of contemporary events. What is implied of the European economic collapse comes from references to the exchange rate and an obsession with money. According to the Hemingway authority Scott Donaldson, money is central to the moral code of the novel: you have to pay for what you get in life. Those who earn their money, like Jake and Bill, are to be trusted. Those who are improvident, like Lady Brett Ashley, the novel’s femme fatale, are not. Although all the men are attracted to Brett, the novel’s true magnet is Hemingway’s alter ego Jake. He is a man who is trusted, even loved, by all. As his friend Bill Gorton says, ‘You’re a hell of a good guy.’ Jake is as attractively sour as Clark Gable’s newspaperman in It Happened One Night (1934), and as observant and passive as that other great Jazz Age narrator Nick Carraway in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925). A war wound has literally emasculated him, eternally frustrating his relationship with the lovely, alcoholic Brett. Nevertheless his passion for her is undiminished, as is his enthusiasm for the ‘manly sports’ of drinking, fishing and bullfighting. If Jake is the moral compass of the novel, Brett Ashley is its magnetic storm. Another character, Robert Cohn, calls her Circe, since she has men behaving like swine. Brett is chronically unreliable, but enchanting, independent and tough. Jake tries to shield her from the blood of the gored steers, but she enjoys seeing how the bulls work, shifting horns like boxers. In public she is a delicious drunk. In private she is a pitiable figure, confessing to Jake at one point, ‘I’ve never been able to help anything.’ She seduces the young bullfighter, ‘the Romero Boy’, and claims she has lost her self-respect as a result. However, she finally lets the bullfighter go, explaining to Jake, ‘You know it makes me feel rather good deciding not to be a bitch.’ Other characters contribute to the gaiety. The two war veterans Bill Gorton and Mike Campbell, the latter a Scots bankrupt and nominally the wayward Brett’s fiancé, are both drunks. There is much humour in their dialogue, as when Bill declares that stuffed animals are needed to brighten up a place:‘What’s the matter with the old one?’ I asked. ‘He hasn’t got any passport.’ I offered the guard a cigarette. He took it and thanked me. ‘What will he do?’ I asked. The guard spat in the dust. ‘Oh, he’ll just wade across the stream.’

Balancing this, much of the pain in the novel comes from the treatment of Cohn, a wealthy Jewish writer (who has boxed but not seen war). Everyone takes a turn at being contemptuous of Cohn. His sin is his jealous obsession with Brett. The native characters show more self-restraint and are rendered charming by the formality of their English, particularly Romero the handsome young bullfighter and the Greek Count Mippipopolous, both conquests of Brett’s. Hemingway’s spare, modernist, ‘hard-boiled’ style has been as easy to parody as the author himself. It is artfully simple, repetitive, uncluttered, fond of conjunctions and distrustful of adjectives. It is a style difficult to get right convincingly, even for Hemingway (eventually it became a mannered affair, tipping toward self-parody). However, The Sun also Rises is superbly done, concise and credible. It is also vividly convincing, because Hemingway had learnt the trick of realism early. So for example, Jake apologizes part way into the novel for not getting a character right: ‘Somehow I feel I have not shown Robert Cohn clearly.’ It is a device that allows us to see Jake as an open-minded fellow. The truth is that showing a thing clearly and therefore achieving the sense of being there is the great strength of Hemingway as a writer. We see it in The Sun also Rises in its artful simplicity:See that horse-cab? Going to have that horse-cab stuffed for you for Christmas. Going to give all my friends stuffed animals. I’m a nature writer.

Throughout his writing career, according to Michael Reynolds in his fascinating Hemingway: The Paris Years, he gave his readers ‘what he later called “the way it was”: the people, the weather, the look andfeel of a place, the small detail capturing on paper the intensemoment forever fresh’. The point, as Hemingway himself explained, was to ‘write one true sentence, and then go on from there’. The Sun also Rises is admittedly not to everyone’s taste. The casual, repetitive anti-Semitism is off-putting: critics have built careers on exploring the issue, as they have with other accusations, of misogyny and homophobia. Bullfighting, too, is deservedly anathema to most of us today. But if one can side-step all that and see the book as of its time, The Sun also Rises is a fine and often hilarious novel with an infectious style. As the trailer for the 1957 Tyrone Power-Ava Gardner film version had it: ‘The Sun Never Rose on a Bolder Hemingway Story!’ If you haven’t read it you should treat yourself. As Nick Adams, his other alter ego, would say, ‘It’s a swell book.’ It may have you swaggering just like Hemingway – at least until the first whiff of tear gas.In the morning it was bright and they were sprinkling the streets of the town and we all had breakfast in a café. Bayonne is a nice town. It is like a very clean Spanish town and it is on a big river. Already, so early in the morning, it was very hot on the bridge across the river. We walked out on the bridge and then took a walk through the town.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 38 © Tony Roberts 2013

About the contributor

Tony Roberts was educated in England and America. After 30 years teaching – an occupation not unlike that of war correspondent – he turned to writing poetry, reviews and essays. His third collection of poems, Outsiders, is published by Shoestring Press.