A tarnished silver teapot. A tin of buttons, their parent garments long decayed. A bundle of yellowing letters, in my mother’s hand. Look: here she is, smiling in her nurse’s uniform in the photograph that used to sit upon the mantelpiece. But now she’s propped against moving boxes, still not unpacked. These are a few of the reasons why I cannot sit in my own front room, although there are more.

It’s no use turning to Marie Kondo in this sort of situation; what I recommend is Elizabeth Gaskell. The narrator of Cranford (1851–3) knows all about hoarding. ‘String is my foible. My pockets get full of little hanks of it, picked up and twisted together, ready for uses that never come.’ And elastic bands – or, as Cranford puts it, India-rubber rings. Oh, don’t talk about India-rubber rings! ‘I have one which is not new,’ our narrator tells us, ‘one that I picked up off the floor, nearly six years ago. I have really tried to use it: but my heart failed me, and I could not commit the extravagance.’

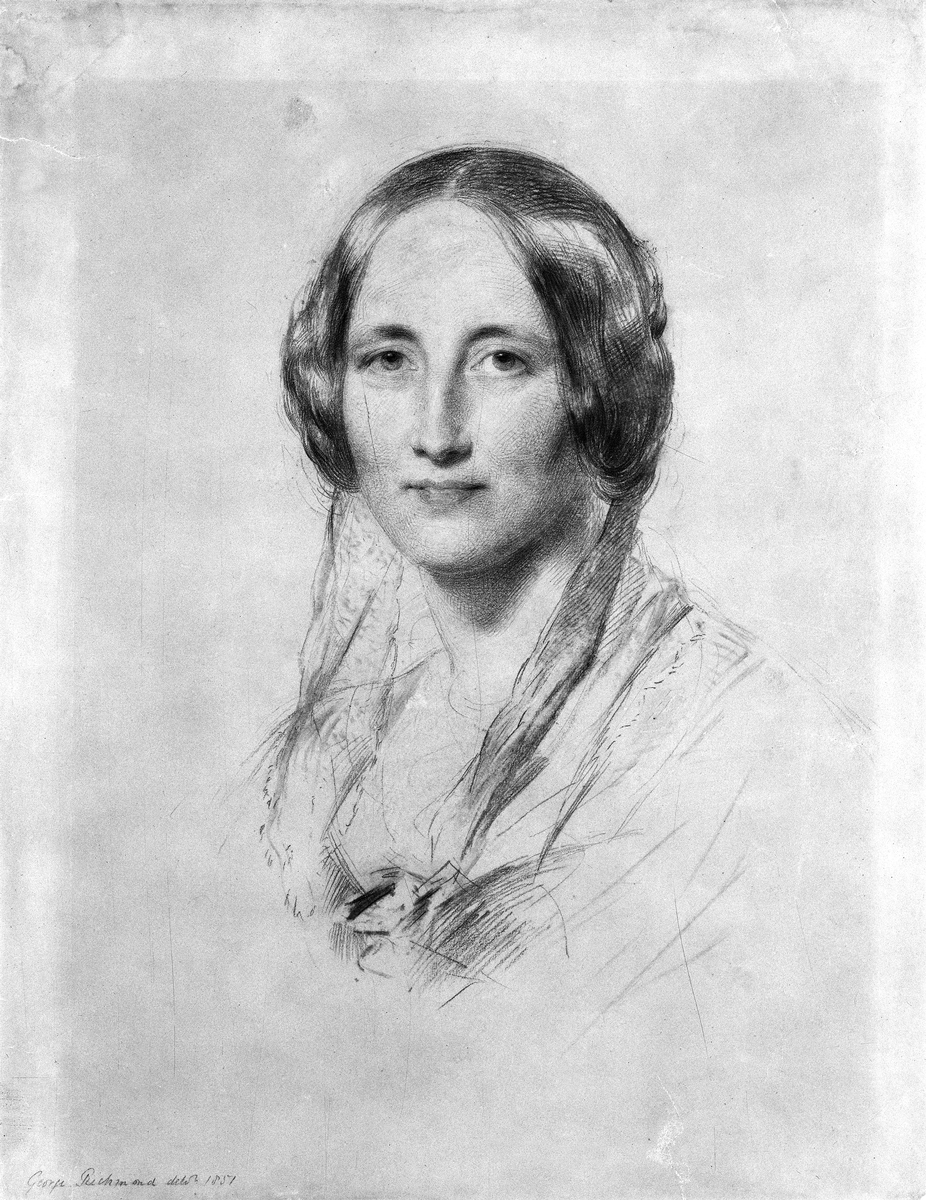

Hoarding string might seem a perverse way to come at the charm of Cranford, Elizabeth Gaskell’s much loved but somewhat under-valued series of stories from the early 1850s. But it is a telling image. Cranford is all about how we cling to the past, for good or ill: it is a novel about the pleasures, and pain, of nostalgia – the hank of string we cling to, lest we unravel altogether.

Ostensibly, Cranford is a gently comic novel of English village life: old maids, tea-trays, curtained drawing- rooms. It takes the form of a series of recollections of Gaskell’s own youth in Knutsford, where she spent her childhood in the 1810s, a railway ride away from Manchester. Knutsford retains something of its rural quaintness even now, especially the churchyard of the Dissenting chapel where Gaskell i

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inA tarnished silver teapot. A tin of buttons, their parent garments long decayed. A bundle of yellowing letters, in my mother’s hand. Look: here she is, smiling in her nurse’s uniform in the photograph that used to sit upon the mantelpiece. But now she’s propped against moving boxes, still not unpacked. These are a few of the reasons why I cannot sit in my own front room, although there are more.

It’s no use turning to Marie Kondo in this sort of situation; what I recommend is Elizabeth Gaskell. The narrator of Cranford (1851–3) knows all about hoarding. ‘String is my foible. My pockets get full of little hanks of it, picked up and twisted together, ready for uses that never come.’ And elastic bands – or, as Cranford puts it, India-rubber rings. Oh, don’t talk about India-rubber rings! ‘I have one which is not new,’ our narrator tells us, ‘one that I picked up off the floor, nearly six years ago. I have really tried to use it: but my heart failed me, and I could not commit the extravagance.’ Hoarding string might seem a perverse way to come at the charm of Cranford, Elizabeth Gaskell’s much loved but somewhat under-valued series of stories from the early 1850s. But it is a telling image. Cranford is all about how we cling to the past, for good or ill: it is a novel about the pleasures, and pain, of nostalgia – the hank of string we cling to, lest we unravel altogether. Ostensibly, Cranford is a gently comic novel of English village life: old maids, tea-trays, curtained drawing- rooms. It takes the form of a series of recollections of Gaskell’s own youth in Knutsford, where she spent her childhood in the 1810s, a railway ride away from Manchester. Knutsford retains something of its rural quaintness even now, especially the churchyard of the Dissenting chapel where Gaskell is buried, but it has had an infusion of football money. The streets are cluttered with expensive cars and the houses gleam with wealth in a way which would have been so distasteful to the spinsters of Cranford. The elderly women who live there are all adept at the art of ‘elegant economy’, trimming their candles watchfully, mending, making do. Not, you understand, out of necessity, but purely a question of choice and good breeding: spending money being ‘always “vulgar and ostentatious”’. This is a world carefully buttressed with old-fashioned silver, with bread and butter sliced wafer-thin, with jealously preserved distinctions of rank and breeding. In this little rural kingdom we seem to be very far from the big social and industrial tribulations of Gaskell’s other novels, the class battles of Mary Barton or the historical sweep of Sylvia’s Lovers. The dramas here are all local. Betty Barker’s cow – of wonderful intelligence, and greatly superior milk – tumbles into a lime-pit and has to have a flannel waistcoat made to keep her from the cold. There is a report that a headless lady ghost has been seen in Darkness Lane. Mrs Forrester’s lace, put to soak in milk, is swallowed by her cat. There is a dispute about the superiority of Dr Johnson over Charles Dickens. We see all this through the eyes of the young narrator, Mary, who goes to stay in Cranford with Miss Deborah and Miss Matty Jenkyns, elderly, straitened, but still highly conscious of their status as the Rector’s daughters. Mary is affectionately, humorously tolerant of these Cranford eccentricities, and the spinsters’ contrivances to preserve the remains of their gentility. That fine old lace, for example, ‘the sole relic of better days’, is rescued from its fate with the help of an emetic, administered to the cat in a teaspoon of currant-jelly: and now, as its owner proudly says at a tea-party, you ‘would never guess that it had been in pussy’s inside’. But holding on to the past too tightly is also a curse. As the meandering recollections of Matty Jenkyns unfold in Cranford so too does our sense of sadness. Class distinctions, the source of so much comedy in the novel, are seen to have ruined her life, since she was forced to give up her suitor in early youth: ‘they did not like Miss Matty to marry below her rank’. In Cranford, Gaskell shows how hard it is to outwit prejudice and fear, to overcome the pressure of the past and the dread of the judgement of others. And, especially, how hard it is to live up to the fearful ambition of a parent. Her style, as she unfolds Miss Matty’s loss and secret pain, is close to the radical delicacy of Jane Austen. We are reminded of the revolutions in feeling of a Box Hill snub, or the pierced and silent heart of Persuasion, all conducted in the corner of a sitting-room, with the teapot standing by. And just as in Austen’s fiction, where the plots are shaped by the Napoleonic wars off-stage, in Cranford, we feel, even if we do not see directly, the upheavals of the nineteenth century: war, empire, rapacious industry. Gaskell, of course, knew these changes at first hand. She was as keen a social observer as Dickens, always alert to the cruelty visited on the poor and the powerless. Indeed, the first story about Cranford was written for Dickens’s journal Household Words and appeared on 13 December 1851. Over the months that followed Gaskell was drawn into further recollections of her life and circle, which were finally published together as the book Cranford in 1853. It was slow going, because at the same time she was also writing her three-volume novel Ruth. Together the two works show us something of Gaskell’s versatility and courage as a writer. Ruth is about the seduction of a young, orphaned seamstress by a feckless aristocratic son. Taken in and protected by a Dissenting clergyman and his sister, Ruth has her baby, and is passed off as a widow, only for her past to resurface and her façade of respectability to be destroyed. She finally emerges a heroine, albeit a dead one, since she becomes a selfless and beloved nurse who perishes in the service of others. The novel is a devastating condemnation of social hypocrisy. What also stands out is Ruth’s joy in her illegitimate baby. It was not simply the book’s portrayal of the fallen woman, but the fallen woman’s pleasure in motherhood, that shocked its early readers. Old friends and newspaper reviews alike expressed their ‘deep regret’ over Gaskell’s choice of subject. Two members of one congregation burnt the book; ‘a third has forbidden his wife to read it’; one young man piously declared he would not allow his mother to read it. The furore put Gaskell into a ‘Ruth fever’, a real bout of sickness which laid her low, depressed and self-questioning. She emerged, however, to publish Cranford later the same year, which was read by relieved critics as a return to form, and a much more suitable and appropriate choice of subject. But the two are interlinked. The ladies of Cranford are haunted by just the same fears that torment Ruth: pain, poverty and death. There is something else which unites the different aspects of Gaskell’s fiction: at its heart is grief. For though her writing was in part prompted by her sense of social justice, it was also a consolation, a distraction and an occupation after the death in infancy of her little boy Willie, her second child, from scarlet fever. In April 1848 she wrote to a family friend: I have just been up to our room. There is a fire in it, and a smell of baking, and oddly enough the recollections of 3 years ago come over me strongly – when I used to sit up in the room so often in the evenings reading by the fire, and watching my darling darling Willie, who now sleeps sounder still in the dull, dreary churchyard at Warrington. That wound will never heal on this earth, although hardly anyone knows how it has changed me. Her writing is always preoccupied with that wound. It pays close attention to the ebb and flow of recollection, of affection that exists only in memory, and it is especially interested in the currents of parental love. In Ruth we see mother and baby; in Cranford time stretches back and we see the old ladies as the cherished infants they once were, though they themselves have no one but their naughty pussy-cats to dote on. There is nothing so tender and elegiac in the whole of nineteenth-century literature as the scene where Miss Matty burns the family letters, lest they fall into the hands of strangers:There was in them a vivid and intense sense of the present time, which seemed so strong and full, as if it could never pass away, and as if the warm, living hearts that so expressed themselves could never die, and be as nothing to the sunny earth.Here are the courtships of the 1770s, here are the announcements of new babies, now in the grave. How well Gaskell evokes the pathos that lies in the box of browning letters, the contrast between the longed-for child of the last century and the ‘grey, withered, and wrinkled’ woman she has become; the mother’s hopes and the sad disappointments of the unfolding years. This is, in truth, why I love the novel so much. Its loving portrayal of mothers becomes mixed up in my memory with my own mother. Cranford was a sacred book in our house, for it had tempted my mother into marriage. She was a nurse at the Manchester Royal Infirmary when my father came in with a detached retina. She had no time for courting: she was set upon becoming a Salvation Army missionary. Staunchly, she rebuffed him: but he held out the promise of a trip to Knutsford in his Morgan, simply to admire the haunts of Mrs Gaskell. What could be the harm? I was the cosseted child of their old age, with whom she recollected the past and thought over how things might have been. It was only to me that she confided the poverty of her childhood, how hard she’d worked to smooth out her Lancashire accent and make herself into someone new. She had a special sympathy for all the small social snobberies of the ladies of Cranford, and their elegant economies. How secretively she guarded where she’d come from, before her glorious reinvention when she was accepted by the nursing school (the first ever without a school certificate – even now I feel a pang, part pride, part disloyalty, revealing that in print). How glad she was to own her own silver, when she’d begun by polishing that of other people; how shamelessly proud of my own school certificates. Yet how carefully she preserved things that might be used again, just in case dark times returned. And now, like the ladies of Cranford, I can’t bear to part with her hoarded treasures, her old-fashioned silverware, my grief. But if Cranford is about the pain of the past it is also about how to let it go. In burning those letters, Miss Matty lets in a beam of light. Though she will never have her love affair, she allows her maid to have her young man come calling: ‘“God forbid,” said she, in a low voice, “that I should grieve any young hearts.”’ And when the bank fails, taking with it all her worldly goods, she enters on a new phase, selling tea and comfits from her own front room. She does nothing so ungenteel as turn a profit, but she’s sustained by the love and friendship of those around her – and she ends by gaining something much more precious, a fragile happy ending in old age. I open the door of the front room, just a crack. There is the teapot, blackened, baleful, looking as if it might have put on mourning itself. Perhaps I’ll start with that. In honour of Miss Matty, I’ll brew some orange pekoe. I might even tidy the letters and tie them with fresh string.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 76 © Felicity James 2022

About the contributor

Felicity James grew up about twenty miles outside Manchester, and at least eighty years behind the times. She owes her existence to Cranford, and now repays the debt by researching Dissenting writers from the Lambs to Elizabeth Gaskell. You can also hear her in Episode 24 of our podcast, discussing the lives and letters of Charles and Mary Lamb.