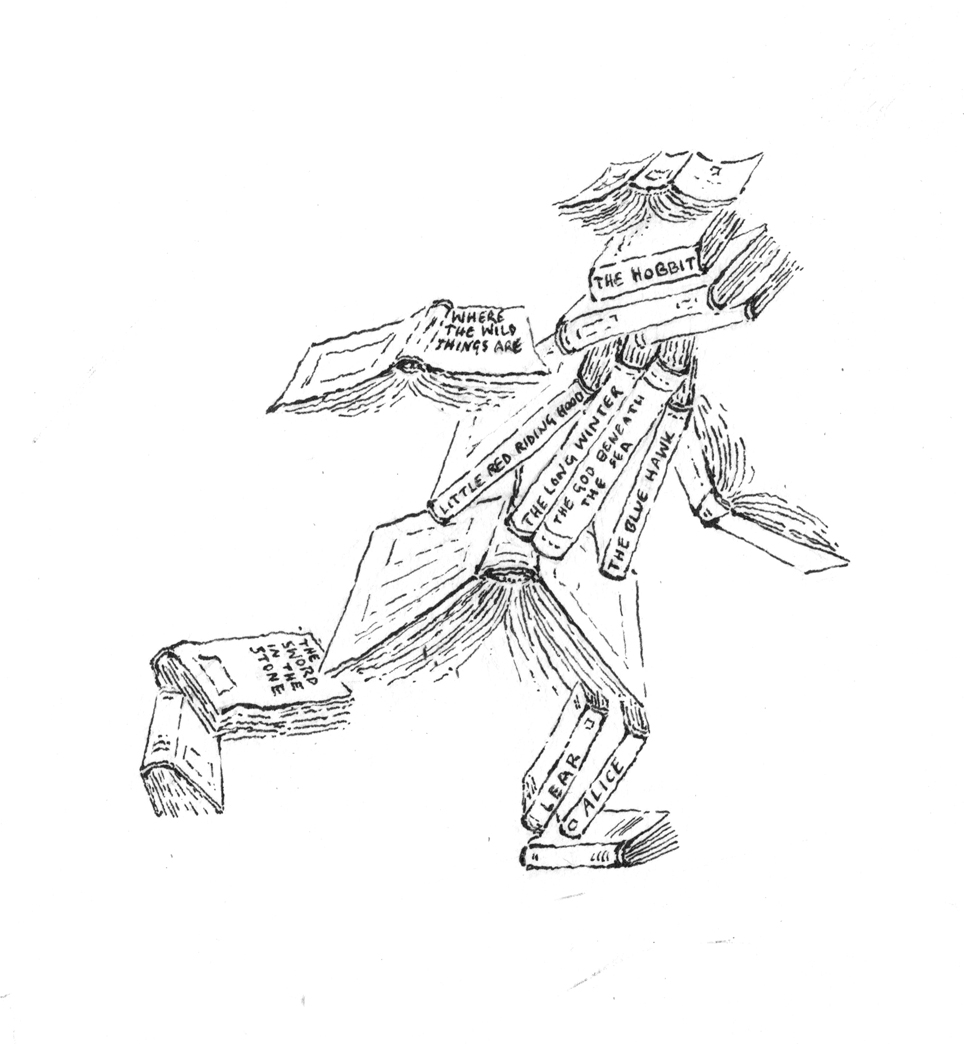

Francis Spufford’s The Child that Books Built is a short book that seems long, expansive, excursive. Of course – it cites a host of other books, from Where the Wild Things Are through The Little House on the Prairie to Nineteen Eighty-Four; it is packed with reference, with discussion. A book about books and, above all, a book about the power of books, about the manipulative effect of fiction, about the way in which story can both mirror and influence the process of growing up. A child learns to read, discovers the possibilities of that retreat into the pages of a book, and its life is never quite the same again.

Francis Spufford describes his own childhood reading addiction and, in the process, dissects with wit and erudition the significant forces at work behind fairy story, behind mythology, behind such archetypal story-telling as science fiction, behind the eventual complexity of novelists such as Borges and Calvino. He charts his own reading life, from the moment ‘the furze of black marks between the covers of The Hobbit grew lucid, and released a dragon’ to his adolescent forays into meta-fiction, stories about stories.

What have books done, for the reading child? Spufford is clear: ‘They freed us from the limitatio

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inFrancis Spufford’s The Child that Books Built is a short book that seems long, expansive, excursive. Of course – it cites a host of other books, from Where the Wild Things Are through The Little House on the Prairie to Nineteen Eighty-Four; it is packed with reference, with discussion. A book about books and, above all, a book about the power of books, about the manipulative effect of fiction, about the way in which story can both mirror and influence the process of growing up. A child learns to read, discovers the possibilities of that retreat into the pages of a book, and its life is never quite the same again.

Francis Spufford describes his own childhood reading addiction and, in the process, dissects with wit and erudition the significant forces at work behind fairy story, behind mythology, behind such archetypal story-telling as science fiction, behind the eventual complexity of novelists such as Borges and Calvino. He charts his own reading life, from the moment ‘the furze of black marks between the covers of The Hobbit grew lucid, and released a dragon’ to his adolescent forays into meta-fiction, stories about stories. What have books done, for the reading child? Spufford is clear: ‘They freed us from the limitations of having just one limited life with one point of view; they let us see beyond the horizon of our own circumstances.’ Quite so. Reading is not escape – though it can indeed be that too; it is the discovery of alternative existences, where things are done differently. It is the discovery of our own disturbing nature, as we see a little boy tame the rampaging, snorting monsters of his own anger in Where the Wild Things Are. It is the discovery of the moral obligations of adult society, as we endure The Long Winter with Laura and her family in a snow-bound town in Dakota. We are condemned to live one life – as me, myself, in the prison of my own mind; but no, we are not, we discover – through reading we can live many lives, and thus we learn how better to manage our own. It is a gloriously universal piece of writing. All readers who have themselves been built by books will be nodding in agreement or making further suggestions. My own response when first I read The Child that Books Built, I remember, was: why has no one written this book before? But Spufford has written it magisterially, eclectically. I was nodding fervently at his salute to the robust, adult-free world of Arthur Ransome’s sailor children, which enthralled me as a 10-year-old in hot, dusty Egypt, reading in wonder of this mythic place of water, greenery and independence. I had to part company with him when it came to his enthusiasm for the Narnia books, which I cannot abide. But of course I never knew them as a child, only met them as an adult and disliked that creepy lion, the Christian message; that perhaps makes all the difference, the reading perspective – child or adult. Though I would certainly contend that if a children’s book is any good it must be as readable for an adult as for a child. W. H. Auden put it perfectly: ‘There are good books which are only for adults, because their comprehension presupposes adult experiences, but there are no good books which are only for children.’ Absolutely. Though I would want to make a qualification: some books may serve to introduce adult experience in a way that expands rather than confuses the child’s perception of the world. But, centrally, it is the abiding quality of the immortal writing that seizes anyone of any age, which means that for those lavishly supplied with reading matter as children it is the language and images of the greats of children’s literature that lodge in the head for ever. Never mind everything that gets shovelled in later, the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter, the Jumblies, the Owl and the Pussycat and so much else will always surface, the essential sediment of a reading lifetime because this was the real thing, the combination of story, originality and imaginative power. ‘A memoir of childhood reading’, Spufford calls his book, and it is a memoir also of a childhood haunted by the tragedy of his younger sister, Bridget, who suffered from cystinosis – a condition so rare that there were at the time only twenty others with it in Britain. Management of this debilitating illness drained her parents, dominated family life. Her older brother fled into books – in denial, in retreat. At the age of 7 he learnt that Bridget was going to die. He was reading mythology at the time – The God beneath the Sea by Leon Garfield and Edward Blishen – and was able to see the savagery of this undeserved verdict as a reflection of the harsh realities of the world of mythology. Terrible things happen to the good just as much as to the bad: misfortune is randomly dealt. A defining moment for the 7-year-old, which seemed to run parallel with his reading experience. He had been familiar with fairy tales, in which ‘character is destiny . . . you can predict what will happen to a good princess, just from the fact that she is a good princess’. Fairy tales are inhabited by types: witches, fairy godmothers, wicked stepmothers. Back in their distant past, they served up hope to a credulous peasantry, for whom not much went right: evil does get its comeuppance, virtue can be rewarded. In the nurseries of the twentieth century they were the archetypal story – this happens because someone did this or that, and the consequence was . . . Or, if you subscribe to the darker theories of Bruno Bettelheim, each tale is vehicle for the struggle between the id and the ego. I remember being uncomfortably fascinated by Bettelheim when I was a young mother, nervously reading Little Red Riding Hood or whatever to the children and hoping their tender minds were not being thrown into turmoil. I am relieved to read that he is somewhat discredited nowadays. Spufford’s analysis of his response to reading is in effect the story of his growing up, of the maturing mind. His intriguing discussion of the moral pointers implicit in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s The Long Winter demonstrates how ‘I learned what people did and did not owe each other’. This story of the inhabitants of a snow-bound town in the nineteenth-century American Midwest, who save themselves and one another when food begins to run out, taught a late-twentieth-century boy the rules of social obligation. He sees the identifying features of children’s literature as that essential component of story married with a structure of judgements, the provision of moral experience alongside compelling atmosphere. And then there comes the dismaying moment when the voracious exploring adolescent reader is impelled to move on – to read wider, further. But where, what? Oh yes, I remember too – that baffled engagement with ‘grown-up’ books, which were both alluring and often obscure. Spufford compares the relative certainties of children’s literature with the deliberate – and desirable – ambiguities of adult fiction. It is a quantum leap for the 15-year-old to take that on. And then there is the question of gender; boys do indeed seek out one thing, girls another. Spufford relished James Bond: Jane Austen did not appeal. He found science fiction, and became an addict. He flirted with pornography – pretty soft porn, by the sound of it, but I am no authority. And, fully fledged as an adult reader, he grew wings and took off with Jorge Luis Borges, with Italo Calvino, with the whole complex fictional riff of stories about stories. It is almost as though his reading has gone full cycle, from the discovery that narrative exists to the dissection of the very concept of story. And, along the way, a mind matures. Read this book, and you will at once be set thinking about the way in which you too have grown up with books – been built by books. Differently so, of course – we all read differently – but there will be plenty of overlap, plenty of excited recognition. Peter Dickinson – oh yes, The Blue Hawk. Joan Aiken – yes, yes. The Sword in the Stone – oh, indeed yes. This is what makes cultural community. You think that you are alone with a book; in fact, you become one of a crowd. Which is fine – and each of us will take something different from that book. And grow up differently.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 42 © Penelope Lively 2014

About the contributor

Penelope Lively once had the temerity to write for children, but has not done so for decades. The Folio Society is about to produce an edition of The Ghost of Thomas Kempe, which would astonish her alter ego who wrote it so long ago.