One of the great advantages of running an auction house for books is that you see a vast range of publications. And if you’ve been a publisher for many years before you became an auctioneer, you frequently wonder what on earth possessed publishers of earlier generations to select some of the incredible rubbish that saw the light of day. But you do find the odd unknown pearl among the dross. I happened to be interested in the short story, and after the First World War collections of these were published in large numbers. Among them a name, a strange name, figured fairly frequently – that of H. A. Manhood. His own story is interesting.

He was born in 1904 and died fairly recently, in 1991. At the age of 23 he sent a selection of twelve stories he had written to Andrew Dakers, who was a literary agent as well as a publisher. Dakers was instantly and deeply impressed by the quality of Manhood’s work. At the time, John O’London’s Weekly (founded in 1919) was the principal literary journal for middlebrow readers, and every young writer’s ambition was to be published by it. Dakers sent the stories to George Blake, the then editor, who responded by return to say that he wanted to publish at least two of the stories at once. The first, ‘Brotherhood’, appeared in the issue of 11 June 1927. Two others followed in August and October. Somerset Maugham chose ‘Brotherhood’ twenty-four years later for Great Modern Writing, an American anthology, and it was also included in The Best Short Stories of 1927.

On hearing the good news, Manhood brought Dakers carbon copies of the stories, which Dakers sent to Jonathan Cape. Only days later, Cape accepted the stories for volume publication. And after a matter of weeks, Viking Press in New York cabled an offer for the American book rights. So impressed were Cape and Viking by Manhood’s talent that when they heard he lived in straitened circumstances and could not support himself

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inOne of the great advantages of running an auction house for books is that you see a vast range of publications. And if you’ve been a publisher for many years before you became an auctioneer, you frequently wonder what on earth possessed publishers of earlier generations to select some of the incredible rubbish that saw the light of day. But you do find the odd unknown pearl among the dross. I happened to be interested in the short story, and after the First World War collections of these were published in large numbers. Among them a name, a strange name, figured fairly frequently – that of H. A. Manhood. His own story is interesting.

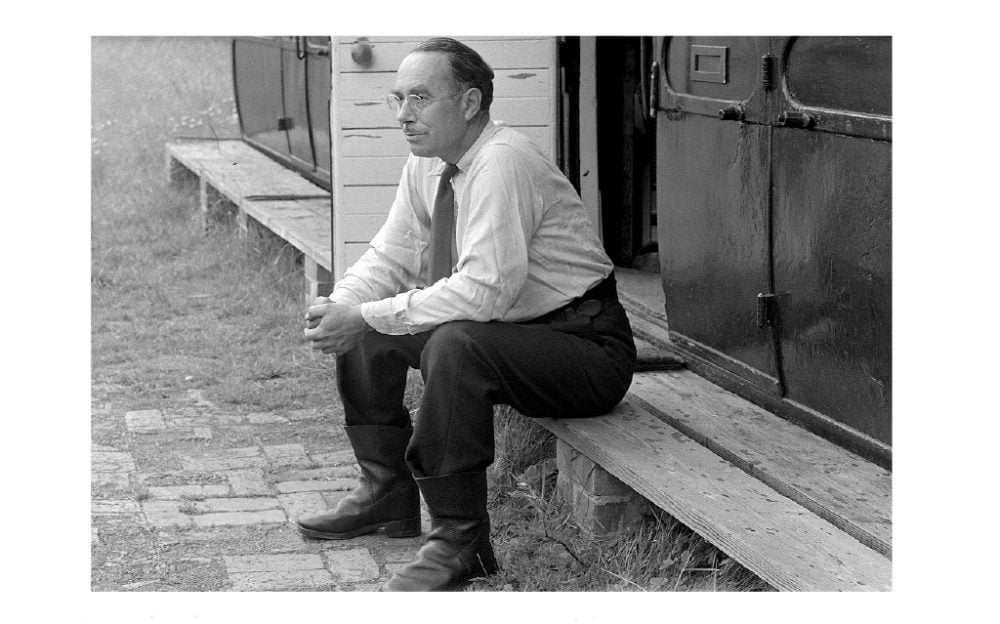

He was born in 1904 and died fairly recently, in 1991. At the age of 23 he sent a selection of twelve stories he had written to Andrew Dakers, who was a literary agent as well as a publisher. Dakers was instantly and deeply impressed by the quality of Manhood’s work. At the time, John O’London’s Weekly (founded in 1919) was the principal literary journal for middlebrow readers, and every young writer’s ambition was to be published by it. Dakers sent the stories to George Blake, the then editor, who responded by return to say that he wanted to publish at least two of the stories at once. The first, ‘Brotherhood’, appeared in the issue of 11 June 1927. Two others followed in August and October. Somerset Maugham chose ‘Brotherhood’ twenty-four years later for Great Modern Writing, an American anthology, and it was also included in The Best Short Stories of 1927. On hearing the good news, Manhood brought Dakers carbon copies of the stories, which Dakers sent to Jonathan Cape. Only days later, Cape accepted the stories for volume publication. And after a matter of weeks, Viking Press in New York cabled an offer for the American book rights. So impressed were Cape and Viking by Manhood’s talent that when they heard he lived in straitened circumstances and could not support himself by authorship, they got together and decided jointly to advance him in monthly instalments a sufficient income on which to live for two years. The result was the issue by Cape of seven books of short stories and one novel by Manhood between 1928 and 1947. The titles in chronological order were: Night Seed (1928); the novel, Gay Agony (1930); Apples by Night (1932); Crack of Whips (1934); Fierce and Gentle (1935); Sunday Bugles (1939); Lunatic Broth (1944); and Selected Stories (1947). Manhood’s last volume of short stories, A Long View of Nothing, published by Heinemann, appeared in 1953. Fierce and Gentle, his fifth book, is particularly interesting. The publisher’s blurb clearly indicates that his earlier books had aroused a great deal of interest (one wonders if they also sold well). ‘Varied in mood, as the title hints, and varied in scene as readers of Mr Manhood’s stories would expect, the new collection of his recent work is outstanding among the short stories of recent years . . . the simple directness of the storytelling is not the least of his merits.’ And to emphasize the point, there is a section at the end of the book entitled ‘Notes’ in which Manhood writes:I have been asked from time to time by people who think me neither vulgar, brutal, sentimental nor ridiculously romantic, how stories begin . . . There is no particular mystery about the process. It simply happens that a word, an incident, heard or seen by chance, seems to illustrate perfectly some tiny bit of one’s philosophy, to underline and explain, at least to one’s own temporary satisfaction, some moment of experience very happily. These are the grains which excite the mind into creating . . .Many of the stories in Fierce and Gentle (as in his other collections) are set in rural communities, villages that may have staggered into the twentieth century but are still deeply immured in the habits of the past. Pubs play a major role. Horses far outnumber cars. The occupations of his characters are primitive. Fishing features frequently, often with an Irish background. There is a succession of elderly spinsters – almost a favourite persona. Many of his characters live on the edge. They suffer from the sort of poverty that we don’t really know today. Where there was no money, there was no food, and people frequently died of starvation. There was no public support, though a limited amount of grudging private charity. Many of Manhood’s stories are what one might call mood-busters. His powers of description are such that they command the reader’s full attention within a very few paragraphs. He clearly had a deep love of wildlife. His knowledge of birds and their habits frequently colours the stories. The same goes for flora – his portrayal of plant life is both erudite and gripping. The most intriguing tale in Fierce and Gentle concerns an old lady called Martha with a passion for wild flowers, who stumbles across a young couple making love inside a thick bower of honeysuckle. A one-time neighbour of Martha’s had been a midwife who had scared her about the evils of sex and, to emphasize this, had left her a book on birth control. Martha rushes home, appalled by what she has witnessed, and feels bound to give the young lovers her book to stop the conception of an unwanted baby. Deeply embarrassed she returns, only to find that the couple are married and have come to this divine spot to conceive their first child. The next story, ‘Poor Man’s Meat’, which is told in the first person, concerns a delightful elderly gypsy couple, travelling about in a horse-drawn caravan. An over-zealous policeman has the husband arrested on a trumped-up charge, for he hates gypsies, and poor old Moses is condemned to three months in prison by the local magistrates. On his release, the couple move on, and the policeman is promoted to another part of the country. Manhood concludes the story, ‘In the process of impounding an ass, strayed from a gipsy encampment, [the policeman] was kicked in the face and his jaw broken and his tongue split so that, forever after, his speech was a brutish, unimportant gibber.’ At Jonathan Cape it was the famous editor Edward Garnett who became Manhood’s mentor and advocate, and who coaxed Manhood through the difficult gestation of his first novel, Gay Agony, if only by occasional gifts of cases of Marsala. It is, I suppose, a moral tale: a protracted fight between good and evil. A young and brilliant engineer is sent to a remote valley to oversee the construction of the sluice gates of a new dam. The man in charge is a swaggering, bullying, womanizing giant who bitterly resents the arrival of this outsider. He contrives to injure the young engineer through a staged accident. Thereafter, a long battle ensues to win the hand of the captivating, scheming widowed landlady of the local tavern, where the engineer is recovering. It must be the longest seduction scene in modern literature, but couched in a language of rare brilliance, with wonderful descriptions of rural life and of the local flora and fauna. The dénouement is shattering, and lets the reader down with an enormous thump. Soon after achieving literary success, Manhood tired of urban life and bought an isolated four-acre plot of land near Henfield in Sussex. On it he placed an old railway carriage which he converted for comfortable living. There he beavered away, coming up to London only to see his publishers, magazine editors and the BBC. He made himself self-sufficient by growing his own produce. After living there on his own for some years, he married. He had certainly been seen as something of a rising star. But after the Second World War, he began to resent growing editorial interference and above all was appalled by the puny payments he received. So in 1953 he bought more land, went in for brewing cider, and never wrote another word. Shortly before his death he contacted me about selling his personal library and also his working papers and archive (it was then that he showed me with fury a letter he had received offering him a mere nine guineas for a long story to be published in a London evening newspaper). He was delighted that I knew his name and knew of his work. I went down to see him and his wife in Sussex in 1990. The railway carriage still existed, but he had been living in a simple bungalow nearby for some years. There I was given the largest helping of smoked salmon and strongly brewed cider I had ever had. At Bloomsbury Book Auctions we had made something of a name for ourselves in selling literary and other personal archives by what is known as private treaty – that is, direct to a library or a university. Manhood’s archive was the most astonishingly complete we had ever encountered. Everything was there and in apple-pie order: notebooks of ideas, early drafts, finished handwritten manuscripts, typescripts, all correspondence with editors and publishers, including his invoices and payment receipts, the reviews of everything he had ever written and all the various editions of the published titles. The final manuscripts had been magnificently bound in vellum by his friend and famous binder, Sandy Cockerell of Cambridge. There were also all his letters from Henry Williamson, Hugh Walpole, John Galsworthy, H. E. Bates and, above all, over a hundred letters from Edward Garnett, not only about Manhood’s work but also full of chit-chat on other Cape authors. And there was the original holograph manuscript of Arnold Bennett’s Evening Standard review of Gay Agony (the word ‘gay’ did not then have the connotation it has today). Manhood wanted it all to go to a library where it could be studied by future generations. He realized that the work of his own generation would be eclipsed in the short term but hoped that interest in it would later revive. It was not easy to sell the material. Manhood’s name had been completely forgotten. So Lord Kerr, my business partner, and I were delighted when it was bought for the British Library by Sally Brown, then in charge of modern manuscript acquisitions. Like us, she had been astonished by the quality of Manhood’s work. Anyone interested can see it – now fully catalogued – in the British Library’s Manuscript Department. Perhaps in conclusion, because it is so typical of his work, it is worth quoting the first paragraph of one of Manhood’s best-known short stories, ‘Thundering Molly’.

That was what they called her through the tenements, but she didn’t care. She was a girl all right, ten years old, tall and thin, and pretty in a sharp boned way, with lolloping black hair, wide defiant eyes and a sudden, startling laugh like bouncing spoons. The only trouble was that she had the temper and beetle-squashing tendencies of a hooligan boy, cursingly fluent in language with a remarkably accurate fist, a liking for slaughter-yards and no gentleness anywhere. God help her, as her grandmother complained sadly and often.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 27 © Frank Herrmann 2010

About the contributor

Frank Herrmann has been a publisher and a senior director of Sotheby’s. In 1983 he founded Bloomsbury Book Auctions, which he ran for 22 years. He is the author of a series of children’s books and an autobiography, Low Profile: A Life in the World of Books.