My father was a bibliophile, a bibliographer and a university librarian for fifty years, and I cannot remember a time when I was without books. It was inevitable, therefore, that I should grow up with an ambition to own and run a bookshop. After thirty years in advertising, I bought a small haberdashery called Stuff & Nonsense in Stow-on-the-Wold. I stripped it of all the racks, previously filled with green anoraks, rolls of furniture fabric, strange hats with earflaps that pulled down or bobbles that stood up, shooting-sticks, carved thumb-sticks and pink wellingtons, and fitted it out with bookshelves.

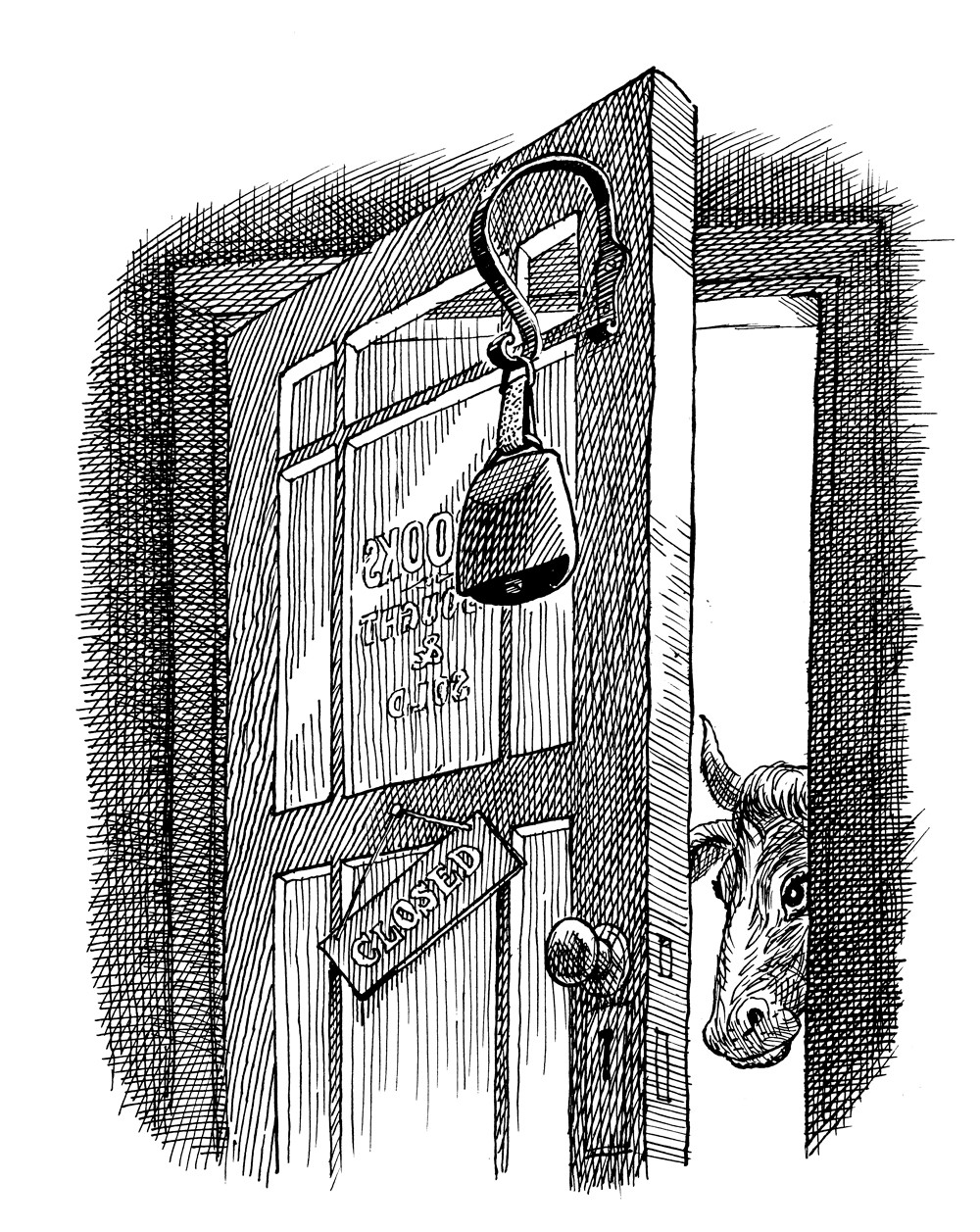

I had already amassed a heterogeneous collection of about a thousand books so that I wouldn’t open with empty shelves. I sat at a small desk facing the front door and the window, where I displayed a varied selection of come-hither titles. An Austrian cow-bell jangled bucolically every time the door opened; in the desk drawer, a cigarbox served as a till and a Balkan Sobranie tobacco tin held coins for change. I was ready.

Customers began to trickle in, encouraging me by saying they were pleased that a second-hand bookshop had opened in the town. Many came in (including the then Foreign Secretary) with plastic bags filled with books they had been waiting to get rid of, and before long I was being asked to visit the homes of people who were about to move, to help them clear out their books. Reinforced by a lifetime of browsing in second-hand bookshops, I found I had little difficulty in judging how to price them.

But not all the time. A small booklet published in India, The Art of Taxidermy: Mounting the Tiger by G. and M. Patel, I had priced at 50p. A lady (and she really was, she was titled) seized the book from the shelves with a cry of delight.

‘How extraordinary! These two brothers stuffed all my husband’s trophies. I must take this. How much is it?’

I indicated the pencilled price.

‘Is that all? I’d have paid £5

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inMy father was a bibliophile, a bibliographer and a university librarian for fifty years, and I cannot remember a time when I was without books. It was inevitable, therefore, that I should grow up with an ambition to own and run a bookshop. After thirty years in advertising, I bought a small haberdashery called Stuff & Nonsense in Stow-on-the-Wold. I stripped it of all the racks, previously filled with green anoraks, rolls of furniture fabric, strange hats with earflaps that pulled down or bobbles that stood up, shooting-sticks, carved thumb-sticks and pink wellingtons, and fitted it out with bookshelves.

I had already amassed a heterogeneous collection of about a thousand books so that I wouldn’t open with empty shelves. I sat at a small desk facing the front door and the window, where I displayed a varied selection of come-hither titles. An Austrian cow-bell jangled bucolically every time the door opened; in the desk drawer, a cigarbox served as a till and a Balkan Sobranie tobacco tin held coins for change. I was ready. Customers began to trickle in, encouraging me by saying they were pleased that a second-hand bookshop had opened in the town. Many came in (including the then Foreign Secretary) with plastic bags filled with books they had been waiting to get rid of, and before long I was being asked to visit the homes of people who were about to move, to help them clear out their books. Reinforced by a lifetime of browsing in second-hand bookshops, I found I had little difficulty in judging how to price them. But not all the time. A small booklet published in India, The Art of Taxidermy: Mounting the Tiger by G. and M. Patel, I had priced at 50p. A lady (and she really was, she was titled) seized the book from the shelves with a cry of delight. ‘How extraordinary! These two brothers stuffed all my husband’s trophies. I must take this. How much is it?’ I indicated the pencilled price. ‘Is that all? I’d have paid £50 for this. Thank you so much.’ The cow-bell rang out the departure of one very satisfied customer, and now I had a coin to rattle in my box. But I had also learned an invaluable lesson. If a book on tigerstuffing could sell like a hot cake in Stow-on-the-Wold, it proved there was a buyer for any and every book; it was just a matter of bringing the two together. From then on I bought arcane and esoteric titles I would previously have ignored, and never regretted it. Within a few weeks, I quickly learned which categories of books and which authors I should concentrate on. I reduced the size of the fiction section; the ubiquitous charity shops provided greater choice. I enlarged the sections of my own special interests – the countryside and children’s books – which remained the largest in the shop, and I also increased religion, cookery, handicrafts, history (especially military history) and biography. Literature was a large section from the start. I learned that demand for the works of Scott, Thackeray, Galsworthy and Hope was negligible but that there was a ready market for Jane Austen, the Brontës, Dickens, Hardy, Trollope, Tolstoy, Waugh and Graham Greene. Poetry was always in demand. I kept two shelves of mixed uncategorized books so that customers could make their own discoveries. I filled boxes with ephemera: postcards, bookmarks (a silk-woven one by Stevens of Birmingham fetched £25), cigarette cards, prints, even a set of glass lantern slides. As the weeks, months and years went by, enjoyment grew. My initial plan of bridging for a couple of years that life-changing transition between being employed and answerable to others and being retired and beholden to no one went by the board. I enlarged the shop, converting the first floor, partitioning off the sink to form a mini-kitchen and adding shelves for a few more thousand books. Then I converted the attic space for another few thousand. My stock capacity increased from the original 3,000 to 10,000 with the result that I stayed happily trading for sixteen years. Every day was different. American tourists flocked to Stow and became valued customers. All were delightful to talk to, especially the better-read of whom there were many. A few let the side down. After a lengthy browse through the literature shelves, one approached the desk with a book in his hand, Samuel Johnson’s Lives of the English Poets. ‘Say, this guy didn’t cover the best ones, did he? There’s no Keats, no Shelley, no Wordsworth.’ In my second year I had a telephone call which resulted in one of my most successful buying coups. A newly arrived librarian at a longestablished boarding-school wanted to clear out all the Victorian leather-bound tomes from the school library to make room for new books. I was invited to make an offer for any book I wanted. The outcome was several car-loads of leather-bound sets of The Edinburgh Review, Household Words, The Quiver, Punch, The Encyclopaedia Britannica and The Quarterly Review, as well as works by Ward Fowler, Richard Jefferies and W. H. Hudson. Within a couple of months, I had sold them all. The leather-bound ones were the first to go, some to local antique shops to decorate their windows, many to Americans who seemed to love any book bound in leather. The Stow horse fair, which is held each May and October, was a mixed blessing. The influx of a thousand or so gypsies and New Age travellers caused many shops to close, though I stayed open. I always kept back a batch of paperback Westerns for one gypsy family who liked to read them in the winter, and during one fair I had a memorable visit. Two customers, in their early twenties, long-haired, clad in black and smelling pungently of wood-smoke, entered the shop. I was on edge, hoping they wouldn’t cause trouble, as they browsed along the shelves, one on each side of the shop. The woman turned to address her companion. ‘Darling, he’s got some George Borrow.’ ‘Has he, sweetie? Get Lavengro if it’s there, would you?’ In fact they bought several books, and they taught me a vital lesson: never judge by appearances – or pungency. There was one aspect of the book trade that I had to learn from scratch: dealing with first editions. Fortunately, I had subscribed to a monthly magazine, Book & Magazine Collector, which dealt with individual authors and their works, and current market prices. The magazine was invaluable, preventing me from making serious mistakes. Chatting with collectors themselves taught me a lot, and there was a lot to learn. The discrimination and fastidiousness which collectors exercise in pursuit of their quarry always amazed me. A first edition had to be pristine, without a mark, a scuff, a blemish of any kind, and the same applied to the dust-jacket. I had a fine first edition of Golding’s Lord of the Flies without a jacket, which I sold for £40. Sometime later, I sold an identical edition with its pristine jacket for £240. The value of that piece of paper was £200 and I soon became wise to the stratagems of some collectors. A later edition of a book would often be published with a jacket identical to that of the first edition. A later edition was cheap. The wrapper was transferred to the jacketless first edition and the value rocketed. There were two aspects of the book trade that always made me uneasy. First editions of children’s books fetched a high price, yet to me it seemed that children’s books were meant for children. This would all too often be brought home to me. ‘Mum, there’s a Rupert annual here. It’s only £95. Can I have it?’ The other was the dilemma posed by selling books with handcoloured plates, most commonly found in pre-twentieth-century natural history books, to customers you knew were print-dealers. They would detach the plates, mount them and sell them individually for anything from £10 to £50 or more. Each volume of Jardine’s Natural History Library, for example, contains thirty hand-coloured plates. From one volume, a print-dealer could make £300 at the very least. (The plates in the volumes Parrots and Pigeons, both by Edward Lear, could bring a return of £1,000 or more.) The market price for a single volume was £40. The print-dealers’ argument was that more people would see and enjoy the plates on their walls at home than would ever be likely to see them in old books, but that argument did not ease my conscience. These aspects apart, what possible reason could I ever have had for giving up this life of bibliophilic bliss? There was no single reason. But I did have an increasing sense of foreboding, which clouded my vision of the future. More and more customers would come in and browse, find a book they wanted and then say they would just check it out on Amazon. I judged the time was right to ease myself out of this wonderfully satisfying and enjoyable occupation. I sold my business as a going concern and I hope that this kind of shop will continue to have a place in the world, albeit a smaller one than hitherto. For what other way of life is there where, if trade is slow, you can pursue your love of reading, and if trade is busy, you know that anyone who steps over the threshold is a kindred spirit? You talk about books, exchange opinions, compare, reminisce and pass the time of day discussing a mutual love. I enjoyed all this for sixteen years. What more could any book-lover want?Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 42 © Glyn Frewer 2014

About the contributor

The leaving card Glyn Frewer’s advertising agency gave him on retirement bore a cartoon captioned: ‘Books Bought, Books Sold, Books Written, Book Mad’ – which was about right.