I discovered Niko Tinbergen’s Curious Naturalists as a student. I was reading psychology and the course had just begun with a look at animal behaviour, which involved a grasp of scientific method and thus a lot of headache-inducing maths. In a bookshop, glumly casting round for some background reading with a lighter touch than the papers I’d been given, I happened on this remarkable book, published surprisingly by Country Life. It was about seagulls, savage wasps, camouflage and other matters now suddenly on my agenda but, because it was for ordinary readers rather than specialists, the ordeals of theory, statistical bafflement and so forth were wonderfully absent. There were plenty of intriguing illustrations too, many of them really quite odd. In one, a man in a floppy hat was presenting a real butterfly with a paper butterfly on the end of a thread. In another, a stuffed fox was being towed by a jeep towards a colony of gulls. Over time I came to relish the contrast between Heath Robinson arrangements like these and the strange truths they could uncover. Even right there in the shop I got a glimpse of the fun there could be in ingenious detective work. That and a sense of how fascinatingly unlike us other creatures are, how remote their realities are from our understanding.

It was Tinbergen’s name that had first drawn me to the book: he was one of my lecturers and it was already clear that this engaging Dutchman would be one of the good things about the course. In those days the department was in a battered Victorian house which might have made a set for Hammer Films, but when he spoke the scene shifted to the breezy sand dunes of the Zuider Zee. His fieldwork there, together with that of a few like-minded others scattered elsewhere in Europe, had effectively created a new science. It was called ethology (from ηθος, meaning custom or character) and it dealt with animals in relation to the disparate worlds they live in, worlds often

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign in I discovered Niko Tinbergen’s

Curious Naturalists as a student. I was reading psychology and the course had just begun with a look at animal behaviour, which involved a grasp of scientific method and thus a lot of headache-inducing maths. In a bookshop, glumly casting round for some background reading with a lighter touch than the papers I’d been given, I happened on this remarkable book, published surprisingly by

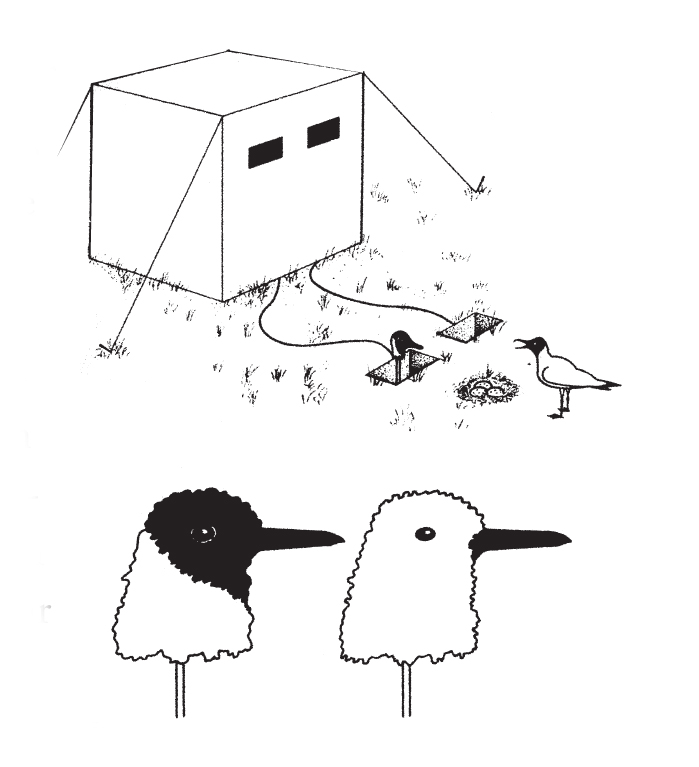

Country Life. It was about seagulls, savage wasps, camouflage and other matters now suddenly on my agenda but, because it was for ordinary readers rather than specialists, the ordeals of theory, statistical bafflement and so forth were wonderfully absent. There were plenty of intriguing illustrations too, many of them really quite odd. In one, a man in a floppy hat was presenting a real butterfly with a paper butterfly on the end of a thread. In another, a stuffed fox was being towed by a jeep towards a colony of gulls. Over time I came to relish the contrast between Heath Robinson arrangements like these and the strange truths they could uncover. Even right there in the shop I got a glimpse of the fun there could be in ingenious detective work. That and a sense of how fascinatingly unlike us other creatures are, how remote their realities are from our understanding. It was Tinbergen’s name that had first drawn me to the book: he was one of my lecturers and it was already clear that this engaging Dutchman would be one of the good things about the course. In those days the department was in a battered Victorian house which might have made a set for Hammer Films, but when he spoke the scene shifted to the breezy sand dunes of the Zuider Zee. His fieldwork there, together with that of a few like-minded others scattered elsewhere in Europe, had effectively created a new science. It was called ethology (from ηθος, meaning custom or character) and it dealt with animals in relation to the disparate worlds they live in, worlds often quite remote from those of other animals, including human animals, even though they may occupy the same space. He was interested in questions most of us don’t even think to ask about the creatures that swoop or buzz past us every day: how they know which creatures belong to their own species; how they evolve in never-ending competition with predators and prey; how their senses differ from our own – sometimes radically; how some individuals start to explore life chances in new, slightly different, environments and perhaps after several generations split off to become new species altogether. Tinbergen had a way of making these questions very immediate. He combined a scientist’s unsentimental approach with a naturalist’s delight in the strangeness and beauty of the creatures he studied, and he seemed not to worry about the kind of figure he might cut. During field work he was quite likely to be found on his hands and knees on the ground, with his arse in the air and some homemade contraption strapped to his face. ‘A pair of lenses’, he wrote, ‘mounted on a frame that could be worn as spectacles enabled me, by crawling up slowly to a working wasp, to observe it, much enlarged, from a few centimetres away. When seen under such circumstances most insects reveal a marvellous beauty, totally unexpected when you observe them with the unaided eye.’ I liked the way he was keen to bring his work to ordinary people as well as to educate scientists and their raw students. So I bought the book. Soon I bought his

The Herring Gull’s World too, which had more to say about the birds he admired so much. He introduced me to a conception of animal experience more elegant and more surprising than my previous misconceptions. Tinbergen spent his childhood summers in a cottage at Hulshorst, an unpopulated place for the most part sandy but with sometimes a thin cover of heather and marram grass and a few undernourished pines distorted by the wind. It was there that, as an undistinguished graduate, he first spotted the creatures that set him on his way. They were wasps, though not wasps of the kind that turn up at picnics. These were solitary, and orange, and they were bringing hapless honey bees to feed their larvae in sand tunnels half a metre below ground. When they were hunting, how did they identify the bees among all the other buzzing insects? And since the nearest hives were a couple of kilometres away, how did they find them, and then find their way home, and then locate the entrances to their tunnels, which they had concealed with sand and which to humans looked exactly like hundreds of other sandy patches? Tinbergen wasn’t content to cite some vague instinct; he wanted to understand the actual mechanisms involved. They would provide a lifetime of absorbed study. First by himself and later with students and followers, Tinbergen deconstructed the experience of the insects, birds, fishes and so on that live around us. The strange pictures in

Curious Naturalists – of fake birds travelling on wires over fish tanks, or of model gulls’ heads made to pop out of the ground like jack-in-the-boxes – illustrated attempts to unravel the ways in which animals master the complex, unpredictable demands of their lives. He soon found that behaviour which looked seamlessly improvised was actually a rapid sequence of quite separate acts, each one immutably fixed by evolution and each one setting off the next. Just as those orange wasps had no discretion over the number of legs they had, so equally they had no discretion over the way that, should their eyes register bee-like movement within half a metre, they would fly downwind to check for a bee-like scent, and, should the scent activate the right receptors in their antennae, they would move to about seven centimetres away and square up for an attack. There was not the least need for intention or foresight on their part. It was because each link in the chain was fixed that Tinbergen could figure out ways to explore them. He could take a fishing line and dangle different things in different ways in front of his wasps until he found that the flight pattern, not the bee itself, was the essential trigger. He could check in the same way that scent and only scent dictated the next move. A wasp would attack even a little twig provided it smelt right. When it came to the way the wasps located their tunnels he could use similar techniques. Flying up from their tunnels once they had concealed them, the wasps would fix in their miniature memories the configuration of little objects – pebbles, scraps of plants – around their entrances. A fly-past of as little as five seconds would be enough for that. Tinbergen could establish which objects they used (not necessarily the ones humans would use) by shifting them in turn a metre or so to one side while the wasps were out hunting. When they returned they would look for their nests in the right place relative to those. He established that wasps manage their long-haul flights to the bee hives and back by much the same means, but using larger landmarks. He and his students explored that pattern by, for instance, stuffing large pine branches in lengths of metal tube, and ramming those into the ground in different spots. All that shifting of vegetation certainly showed dedication. But Tinbergen always showed kindness too: however much he upset their routines he made sure that the wasps got home again afterwards. In fact he surprised himself by becoming attached to them. To tell them apart he had to catch and mark them with tiny dots of water-soluble paint: ‘It was remarkable’, he said, ‘how this simple trick . . . changed my whole attitude to them. From members of the species

Philanthus triangulum, they were transformed into personal acquaintances, whose lives from that very moment became affairs of the most personal interest and concern to me.’ I don’t know whether I was more surprised by Tinbergen’s way of interrogating the natural world or by what it revealed. We all know that evolution shapes bodies and abilities, but it was news to me that actual deeds could be inherited too. If one wanted to personify Nature one could call it a brilliant ruse on her part to make intelligent behaviour possible for creatures without intelligence. As I went on reading the book I was surprised again to find that the same principle operates higher up the evolutionary scale. What makes a hungry herring gull chick gape open its beak is not the prospect of food, or its mother’s tender gaze, but the red patch on the side of her yellow beak. In fact Tinbergen tried an enhanced form of mother’s beak – a yellow-painted stick with oversize red patch and no mother attached. He found the chick gaped wider than ever. Because gulls are social creatures, a lot of the events they respond to are the actions of other gulls, and their responses produce other responses in turn. There are long exchanges where every move has been fixed by evolution. If one gull strays on to another’s nesting territory, that produces in the second gull a particular posture indicating imminent attack, which in turn produces in the first gull another particular posture indicating readiness to clear off. But the gull’s threat only works on its own territory. If it chases its rival on to its territory the tables will instantly be turned. So gulls may absurdly chase each other to and fro, swapping postures, until they reach equilibrium. At that point, with both birds stimulated equally to fight and to fly away, and therefore unable to do either, bizarre and inappropriate behaviour begins. In the case of gulls it’s a wild and indignant nest building, as the birds tear up grass and roots with such force they often fall over. In this way the boundaries are negotiated and fixed. Courtship is even trickier, because potential mates are simultaneously driven to fight, fly away and also have sex. It is this conundrum that has led to the amazing courtship displays so popular with nature programmes. As Tinbergen’s work developed, he would take students with him to help out, and inevitably, in the course of hot days in the bushes or observing birds from hides, a certain amount of human courtship behaviour would go on as well. I used to wonder whether these couples, observing the pair formation of some bird species or other, would observe themselves objectively too and became more self-conscious as a result. That speculation leads to another, more serious one: how high in the evolutionary chain can fixed behaviour sequences be found? In some key areas of behaviour, quite high. Of course the instincts of dogs and their relations are much overlaid by learning, playfulness and other flexibilities, but even so the dominance rituals of their wolfish cousins – which prevent them from using on each other the teeth that so impressed Little Red Riding Hood – are surely one such sequence. (By ironic contrast with wolves, doves have no such ritual and can be absolutely vicious.) Tinbergen may have thought that at some level fixed patterns operated still higher, because at the end of his life he started to bring his ideas to bear on human autism. Some years after I sat rapt at his lectures, Niko Tinbergen won a Nobel Prize. The Tinbergens must have been a clever family because shortly beforehand his brother Jan had achieved one for economics. Niko shared his prize with two other brilliantly original ethologists, Karl von Frisch and Konrad Lorenz. One of von Frisch’s discoveries was the now famous dance by which honey bees will guide others in their hives to a new source of nectar, indicating its distance by the dance’s speed of wiggle and its direction by the angle of the dance to the vertical, which they make equivalent to the nectar source’s angle to the polarization of light. One of Lorenz’s finds was the sensitive period in which newly hatched geese ‘imprint’ on their mothers, whom they afterwards follow everywhere. By imprinting like this they download an image of their future mates as well. He discovered this when a motherless chick imprinted on him, and later was attracted only to bearded zoologists. Of course, one wouldn’t now read Tinbergen himself to become absolutely up to date with his subject. Fifty years is a very long time in science, and though what his books tell us is still broadly valid, the facts and ideas they contain have certainly been extended and refined. But what won’t have been surpassed is the feeling they give of being in at the opening of a whole new field of knowledge, not light years away in space but right here by our sides. As much as they did when first published, his books enlarge our own world by letting us see something of the other worlds which exist in parallel. I have never looked at animals in quite the same way since reading

Curious Naturalists, and for that matter I have never looked at people in quite the same way either.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 19 © Grant McIntrye 2008

Grant McIntyre was never a very brilliant psychology student but still finds the subject fascinating.