The idea of telling a story based on a construction project has been with us since the Book of Genesis, but the method chosen to tell the tale imparted in The Honeywood File, and its sequel The Honeywood Settlement, is by far the most effective and entertaining way I know of describing a process that is at once collaborative and confrontational. Written by H. B. Cresswell, himself a practising architect, The Honeywood File and its successor began life as a series of weekly articles that appeared in the Architects’ Journal between 1925 and 1927, whence they soon gathered enough of a following to be collected and published as books in 1929 and 1930.

The story concerns the building of a ten-bedroomed country house, Honeywood Grange, for a peppery but fair-minded middle-aged financier, Sir Leslie Brash, his neurotic wife Maud and their daughter Phyllis, a bright young thing. The file in question is the architect’s ‘job file’ as it accumulates correspondence in the office of 29-year-old architect James Spinlove, recently established in practice and whose first significant project this is. The job might generate a fee of perhaps £100,000 today.

Most practising architects find themselves with an irate client and/or disgruntled builder at some point, and will be familiar with the dispiriting task of poring over ancient correspondence, trying to unravel the obligations the various parties have to each other in an attempt to stop an argument turning into a lawsuit. When I began working as a trainee architect, I remember waiting in trepidation as my boss looked over a draft of one of my early letters. ‘This is much too chatty,’ he said, crossing out half my effort with a red Pentel. ‘One day we’ll find some clever-dick lawyer reading this out in court and tearing us to shreds with it.’

The reader needs no specialist knowledge in order to enjoy The Honeywood File. I first read it before sitting my p

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe idea of telling a story based on a construction project has been with us since the Book of Genesis, but the method chosen to tell the tale imparted in The Honeywood File, and its sequel The Honeywood Settlement, is by far the most effective and entertaining way I know of describing a process that is at once collaborative and confrontational. Written by H. B. Cresswell, himself a practising architect, The Honeywood File and its successor began life as a series of weekly articles that appeared in the Architects’ Journal between 1925 and 1927, whence they soon gathered enough of a following to be collected and published as books in 1929 and 1930.

The story concerns the building of a ten-bedroomed country house, Honeywood Grange, for a peppery but fair-minded middle-aged financier, Sir Leslie Brash, his neurotic wife Maud and their daughter Phyllis, a bright young thing. The file in question is the architect’s ‘job file’ as it accumulates correspondence in the office of 29-year-old architect James Spinlove, recently established in practice and whose first significant project this is. The job might generate a fee of perhaps £100,000 today. Most practising architects find themselves with an irate client and/or disgruntled builder at some point, and will be familiar with the dispiriting task of poring over ancient correspondence, trying to unravel the obligations the various parties have to each other in an attempt to stop an argument turning into a lawsuit. When I began working as a trainee architect, I remember waiting in trepidation as my boss looked over a draft of one of my early letters. ‘This is much too chatty,’ he said, crossing out half my effort with a red Pentel. ‘One day we’ll find some clever-dick lawyer reading this out in court and tearing us to shreds with it.’ The reader needs no specialist knowledge in order to enjoy The Honeywood File. I first read it before sitting my professional exams in 1976 and have dipped into it at five-year intervals ever since – ‘just to remind myself what fun it was’ – only to find myself going back to the beginning and starting again from scratch. The correspondence appears in chronological order and, apart from a running commentary in the form of footnotes added by the author drawing attention to the correspondent’s style or to some hidden agenda, there is no narrative at all. The cast of characters includes Spinlove, Sir Leslie, John Grigblay of Messrs J. Grigblay & Sons, a builder with whom any architect would be privileged to work, Nibnose & Rasper, the sort of builders I have spent a lifetime trying to avoid, and Bloggs, Grigblay’s foreman – the man actually responsible for building Honeywood Grange to Spinlove’s design, whose virtually illiterate scrawl one can imagine being composed with a screwed-up face and much licking of a rectangular carpenter’s pencil. There are any number of other contributors – brick merchants trying to pass off seconds as facings, oleaginous suppliers of sewerage equipment whose lavender-scented writing-paper offers components for septic tanks that are much more sophisticated and expensive than they need be, a firm of grand solicitors, a pompous KC, opportunistic neighbours with their hands out – each with a style of address that reflects his particular interest in the project. Throughout the construction stage we feel the misanthropic handof Mr Potch, the local Building Inspector, who moonlights as anunofficial ‘architect’ in his spare time. Potch and his cronies in the local Rotary Club resent whippersnappers like Spinlove coming down from ‘Lunnen’ and queering their pitch. Potch’s sole purpose in life seems to be to frustrate Spinlove’s endeavours wherever possible. Their correspondence reveals the world of cosy provincial back-scratchers and price-fixers whose only interest in the construction industry is to make as much money out of it as possible, whereas Brash, Spinlove and Grigblay are co-operating on a project with a more serious cultural intent than they would probably admit. Nothing much seems to have changed in the industry since 1930 although, sadly, firms like Grigblay & Sons are far thinner on the ground, and clients like Sir Leslie Brash, if they are not buying luxury executive dwellings with three-car garages, are refurbishing Georgian rectories rather than building new estates. And, of course, nobody writes letters any more. What The Honeywood File does extremely well is to establish the roles and obligations of the principal players in any serious building project. Spinlove must ensure that Brash procures the house that he, Spinlove, has been commissioned to design, but he must also ensure that Grigblay is properly paid for work that he has been asked to do, even though some of it, much to Spinlove’s discomfort, may not have been included in the tender documents. At the same time, Grigblay needs to maintain his reputation as an excellent builder and to be careful not to drop the inexperienced Spinlove in it or allow him to be bullied by Brash, who is, of course, paying for everything. Like Godfather 2, The Honeywood Settlement is perhaps even more enjoyable than its predecessor. The settlement of a building project’s ‘final account’ takes place during the six-month period after the clients move in and before the final inspection, which occurs only once all outstanding defects have been made good. At this point all final payments are authorized. My own particular interest in this ritual has been the payment of the balance of the architect’s fee. It ain’t over till it’s over. The main thrust of the book deals with the catastrophe that follows as a result of the application everywhere, at a crucial stage of the construction process, of ‘Riddoppo’, a new super-paint that Sir Leslie has been flattered into promoting by one of his business cronies, in preference to the tried and tested paint specified by Spinlove, the properties of which are well understood. Despite the most forcefully presented arguments against adopting this course of action, Sir Leslie has to demonstrate who’s boss. Perhaps a section of the builder Grigblay’s letter to Spinlove, written once the super-paint has begun to demonstrate all the failings he anticipated, will give a flavour of the whole enterprise.There is also an enclosure from Grigblay to Riddoppo dated 27.2.26.Grigblay to Spinlove (12.3.26) The matter I am taking the liberty to write to you privately about is this New Novelty Super Paint the old gentleman insisted I use and which is going to be a bit more of a novelty than he bargained for. The ripple is much more than it was, and is forming in ridges. Sir Leslie may think it looks pretty so, but he will change his mind when it begins to fold over on itself and break away in flakes – which is what comes next, for I found a place behind a radiator in the bathroom where it is doing a bit of private rehearsal. The worst place is on the wall of the kitchen where the furnace flue goes up behind. The maids have brushed it over and washed it down till there isn’t any paint left, scarcely.

As you know, sir, I refused to take responsibility for Riddoppo and gave warning before the painters left the job that it would all have to come off again – except what came off of itself – and I hope you will bear it in mind, because when Riddoppo gets a move on and shows how super it knows how to be (and we shan’t be long now), the dogs will begin to bark; and as I don’t want to be bit, and you, I take it, don’t want to either . . . I take the liberty, with all respect to your superior judgement, of dropping you a friendly hint – which is just to take no kind of notice; and if the old gentleman says anything or makes any complaint, to hold out that the paint is no concern of yours any more than it is mine . . . Please be very careful, sir, what letters you write to Sir Leslie; and do not write Any if avoidable, for lawyers are wonderful fellows at proving words mean the opposite of what they do.

I hope no harm done by me addressing you, but thought best, as I am afraid there is trouble ahead.

I am, sir Yours faithfully

Gentlemen We painted out Honeywood with your Riddoppo Super because we were so ordered, and if you want to know what it looks like better go and see as we only carried out architects orders and it is no more business of ours and we will have no more to do with it.When I first read this saga it was as an architect of about the same age as Spinlove, and I knew little about builders. Thirty years later I know a great deal about them, and I have come to realize not only what a difficult job they do, but also that the good ones often have to be protected from rogue clients. For most people, commissioning building work is not only a mammoth undertaking but also a giant step into the unknown, making them vulnerable to the blandishments of self-interested chancers taking advantage of their inexperience. The process is long, difficult and expensive, and there is plenty of opportunity for such people to appear along the way. After three decades I feel I am just beginning to get the hang of it, and a quinquennial refresher of The Honeywood File and The Honeywood Settlement reminds me how lucky I am to have worked with the John Grigblays (and the Bloggses) of my profession. Anyone who has tried to fit a shelf, stood mystified in a DIY shop or waited in terror for the arrival of an emergency plumber will understand the tale, and anyone interested in reading or writing letters will enjoy the masterful way in which Cresswell has chosen to tell it.

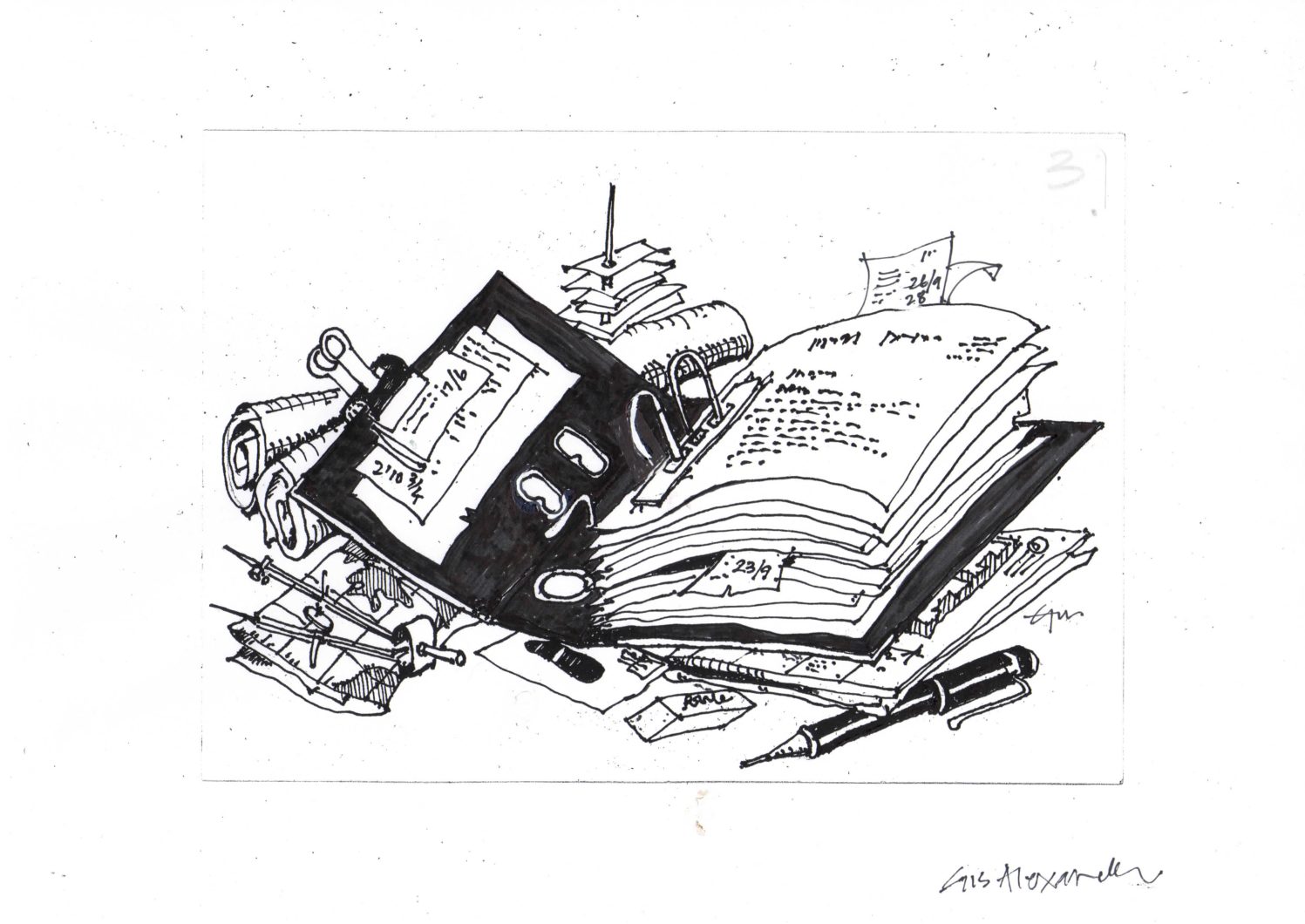

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 40 © Gus Alexander 2013

About the contributor

Gus Alexander set up his own practice in London in 1986 and has been working as an architect and writing about it ever since. He is currently completing an illustrated book of tales from the architect’s life recorded in his own files.

This piece is one of the winning entries in our Older Writers’ Competition.