Question: Fussy people Darwins are, Who’s the fussiest by far?

Answer: Several aunts are far from calm,

But Aunt Etty takes the Palm.

(From Christmas Conundrums, by Bernard)

I have defined Ladies as people who did not do things themselves. Aunt Etty was most emphatically such a person. She told me, when she was eighty-six, that she had never made a pot of tea in her life; and that she had never in all her days been out in the dark alone, not even in a cab; and I don’t believe she had ever travelled by train without a maid. She certainly always took her maid with her when she went in a fly to the dentist’s. She asked me once to give her a bit of the dark meat of a chicken, because she had never tasted anything but the breast. I am sure that she had never sewn on a button, and I should guess that she had hardly ever even posted a letter herself. There were always people to do these things for her. In fact, in some ways, she was very like a royal person. Once she wrote when her maid, the patient and faithful Janet, was away for a day or two: ‘I am very busy answering my own bell.’ And I can well believe it, for Janet’s work was no sinecure. But, of course, while Janet was away, the housemaid was doing all the real work; and Aunt Etty was only perhaps finding the postage stamps for herself, or putting on her own shawl – the sort of things she rang for Janet to do every five minutes all day long.

Aunt Etty was my father’s elder sister Henrietta; and she had married Uncle Richard Litchfield, who worked on the legal side of the Ecclesiastical Commission. The Darwin brothers were always inclined to laugh at him; indeed there still survives the unkind saying of one of them, that ‘Little Richards have long ears’. And, of course, they sometimes laughed at Aunt Etty too! But I liked him very much, because he talked to me as if I were quite grown-up.

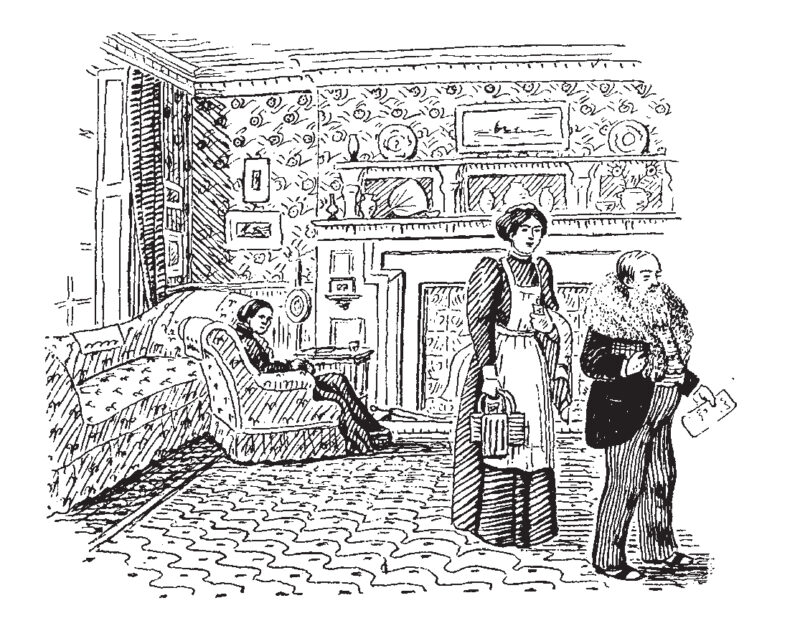

Uncle Richard has been sent to bed, because Aunt Etty suspects him of having a cold. She is feeling very anxious about him. This is their Ruskin and Morris drawing-room at Kensington Square

He was a nice funny little man, whose socks were always coming down; he had an egg-shaped waistcoat, and a fuzzy, waggly, whitey-brown beard, which was quite indistinguishable, both in colour and texture, from the Shetland shawl which Aunt Etty generally made him wear round his neck. For her business in life, her profession, was taking care of healths, her own and other people’s.

She had been an invalid all her life; but I don’t know what (if anything) had originally been the matter with her. I should guess, however, that she had really been delicate when young. Her tiny form, her little monkey hands, seemed to belong to a frail, but wiry, person. But I am quite sure that, with her iron will, she could have ignored and controlled her ill-health, both of the nerves and of the body, if only she had been set off in the right way when young.

The trouble was that in my grandparents’ house it was a distinction and a mournful pleasure to be ill. This was partly because my grandfather was always ill, and his children adored him and were inclined to imitate him; and partly because it was so delightful to be pitied and nursed by my grandmother. She was a most remarkable woman, to outsiders appearing rather stern and alarming, and with great independence of mind. But she was also extremely tender-hearted, and I have sometimes thought that she must have been rather too sorry for her family when they were unwell. A little neglect or astringency might have done some of them a world of good. Hundreds of letters of Grandmamma’s exist, and hundreds more of Aunt Etty’s; and every single one of them, however humdrum, contains some characteristic and charming phrase; and every one of them also contains dangerously sympathetic references to the ill-health of one, or several, of the family. Many of their ailments must have been of nervous, or partly of nervous, origin; of course, there was real physical illness, too, though no one now will ever know how much, for a great deal of illness was left undiagnosed in those days. But of one thing I am quite certain: that the attitude of the whole Darwin family to sickness was most unwholesome. At Down, ill-health was considered normal.

Every time I reread Emma I see more clearly that we must be somehow related to the Knightleys of Donwell Abbey; both dear Mr Knightley and Mr John Knightley seem so familiar and cousinly. Surely no one, who had not Darwin or Wedgwood blood in their veins, could be as cross as Mr John Knightley was, when he had to turn out to dine at the Westons’. ‘The folly of not allowing people to be comfortable at home! And the folly of people’s not staying comfortably at home when they can!’ – it might be Uncle Frank himself speaking. But it is obvious, too, that there is some strain of the Woodhouses of Hartfield in us, of Mr Woodhouse in particular. There was a kind of sympathetic gloating in the Darwin voices when they said, for instance, to one of us children: ‘And have you got a bad sore throat, my poor cat?’ which filled me with horror and shame. It was exactly the voice in which Mr Woodhouse must have spoken of ‘Poor Miss Taylor’. But it had one good effect: it quite cured us of enjoying ill-health. I denied having a sore throat at all if I possibly could.

I have been told that when Aunt Etty was thirteen the doctor recommended, after she had a ‘low fever’, that she should have breakfast in bed for a time. She never got up to breakfast again in all her life. I admit that I know none of the facts, but I cannot think it good mothering on the part of my grandmother to have allowed a child to slip into such habits.

Aunt Etty ordering dinner in her patent anti-cold mask

Extract from Chapter VII: ‘Aunt Etty’

Plain Foxed Edition: Gwen Raverat, Period Piece

© The Estate of Gwen Raverat and Faber & Faber 1952