If we’re honest, most of us have at least one friend who we would hesitate to bring into civilized company – someone too strange or socially awkward, full of crazed notions about God or politics, given to boring on or making horrible scenes: unspeakable when drunk. Something similar holds with writers: there are books and authors that we love quite unreasonably but would hesitate to introduce to anyone nice. Often, these are the authors we read and read again, however many times we’ve given them up in despair or disgust, promising ourselves that we won’t soil another moment in their company. As with many a difficult friendship, you can end up wondering who is abusing whom. Some knotty thoughts arise: doesn’t allowing ourselves to feel ashamed of someone, anyone, always make us feel a bit ashamed of ourselves? Doesn’t it imply a priggishness – at worst a kind of treachery?

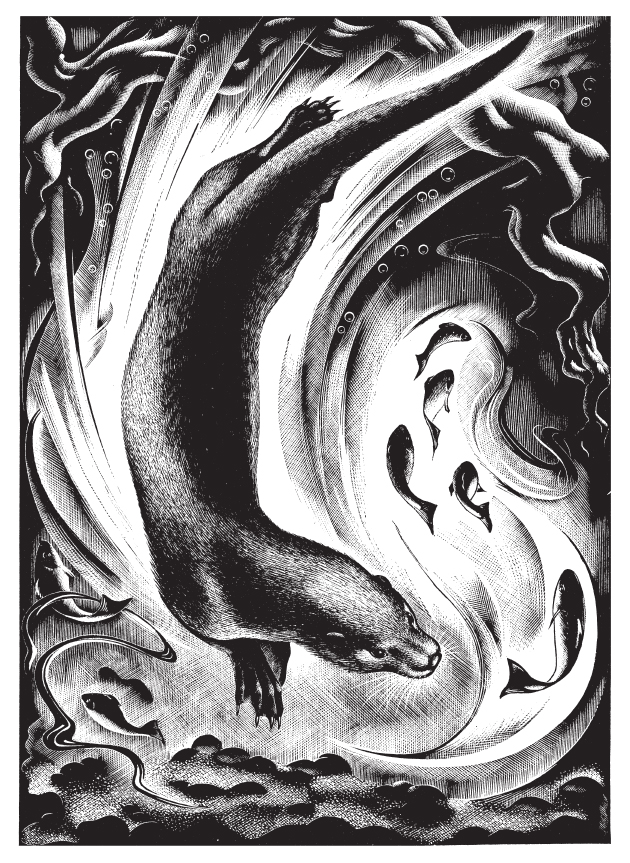

The bothersome chap who prompts these thoughts is Henry Williamson – author of Tarka the Otter (1927), some lesser-known but exquisitely written animal stories, and twenty or so full-length novels, now largely unread except by a small band of cultists. Williamson seems a man made for mixed feelings: a naturalist of rare gifts, a writer with a unique voice and vision, but unquestionably a bore, a crank and – here it gets critical – an overt, unapologetic Nazi. His friends seem to have found him exasperating but lovable – a strangely feral, childlike creature: others saw something very dark and had the perfect ready-made nickname for him: Tarka the Rotter.

There’s a queasy fascination in seeing how this gifted, rather gentle man ended up where he did, a literary pariah still babbling shamelessly about Hitler as a ‘chaste saint above earthly impulses’ and a ‘flawed Christ killed by the lack of imagination of others’ in his novels of the 19

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIf we’re honest, most of us have at least one friend who we would hesitate to bring into civilized company – someone too strange or socially awkward, full of crazed notions about God or politics, given to boring on or making horrible scenes: unspeakable when drunk. Something similar holds with writers: there are books and authors that we love quite unreasonably but would hesitate to introduce to anyone nice. Often, these are the authors we read and read again, however many times we’ve given them up in despair or disgust, promising ourselves that we won’t soil another moment in their company. As with many a difficult friendship, you can end up wondering who is abusing whom. Some knotty thoughts arise: doesn’t allowing ourselves to feel ashamed of someone, anyone, always make us feel a bit ashamed of ourselves? Doesn’t it imply a priggishness – at worst a kind of treachery?

The bothersome chap who prompts these thoughts is Henry Williamson – author of Tarka the Otter (1927), some lesser-known but exquisitely written animal stories, and twenty or so full-length novels, now largely unread except by a small band of cultists. Williamson seems a man made for mixed feelings: a naturalist of rare gifts, a writer with a unique voice and vision, but unquestionably a bore, a crank and – here it gets critical – an overt, unapologetic Nazi. His friends seem to have found him exasperating but lovable – a strangely feral, childlike creature: others saw something very dark and had the perfect ready-made nickname for him: Tarka the Rotter. There’s a queasy fascination in seeing how this gifted, rather gentle man ended up where he did, a literary pariah still babbling shamelessly about Hitler as a ‘chaste saint above earthly impulses’ and a ‘flawed Christ killed by the lack of imagination of others’ in his novels of the 1960s; that, however, is a tale for another time. For the moment, I want to stay with the acceptable side of Williamson and to talk about his best-loved book; a book written almost a decade before he made his fateful visit to Germany and came away with the idea that Hitler – ‘an ex-corporal with the truest eyes I have ever seen’ – shared his own passion for ecology and agrarian reform. But even here, in Tarka, you might think you can see the portents – the little signs pointing to where it would all go so awfully wrong . . . It’s easy to feel attracted to the young Henry Williamson – the nerve-racked war veteran, still in his early twenties, who makes his way to North Devon on a battered motorbike, with a head full of Shelley and Richard Jefferies; who holes up in a tiny damp cottage – soon filled with cats, dogs, owls, gulls, a baby otter – and lives a hermit’s or a tramp’s life, exploring the wild country about him and starting to write it all down. This man we can agree to like, surely: he seems a bit like Snufkin, the unworldly drifter in the Moomin stories. He swims in the nude, he throws apples at local dignitaries, he scandalizes with his wild talk of Lenin and Christ. Okay, so he’s a bit worrying after all, this young man. But there’s something inspiring, too, about the way he comes to write Tarka by a kind of deep immersion – plunging himself into the creature’s habits and habitats, crawling through spinneys and splashing through rivers to get an otter’s-eye view of the world. The tale has been frequently told, perhaps most eloquently by Robert Macfarlane:In these early days, otter-man took the same heroic trouble with his prose as he did with his fieldwork; Tarka was rewritten seventeen times, a few key chapters twice that. Williamson is, or can be, a virtuoso stylist:Daily, for months, he walked out alone into the great wedge of moor that is held between the rivers Taw and Torridge, where they tumble, divergent, off the north-west slope of Dartmoor. During those seasons of river haunting, Williamson lived through the moor’s different weathers. Big scapular-shaped rain clouds, light trimming the wet rocks, coffee-coloured spate-water. At other times, sunlight, softness, wild swans beating through blue sky. Sometimes he slept out overnight, in the lee of a bank or in a stand of trees. He would wake starred with frost, or hung with dew. In the course of that strange and restless time, Williamson became, by his own reckoning, an otter-man.

That’s a fairly randomly chosen piece from Tarka, but surely any Williamson fan would recognise it as his; when he’s writing well, he has a wholly characteristic music – it’s there in the ‘measured beat’ of the long, sonorous cadences, the repeated ‘w’, ‘l’, ‘m’ and ‘s’ sounds (now I come to think of it, the sounds of his own name). It’s a kind of incantation, and Williamson uses it to sing a whole world into being – a dreamlike world of starlit weir pools, precipitous, owl-hushed oak woods, grey plover-haunted estuaries, and high moors of cotton grass and curlew song. There’s a glamour to these landscapes that is almost physically haunting. So Tarka is justly a famous book and probably some kind of masterpiece. But ask precisely what kind and the questions begin to slide and wriggle and bite each others’ tails. The book is as hard to get a hold on as its protagonist – and no more cuddly. The first thought to go has to be that this is in any way kids’ stuff. Of all the strange books that have from time to time been thrust at children, Tarka the Otter must be one of the strangest. Shocking in its violence, heavy with descriptive detail, severely anti-anthropomorphic – it’s a long way from Watership Down, let alone Disney. Any normal child would surely be bored and repelled (though the young Ted Hughes read it compulsively for two years: it ‘entered me and gave shape and words to my world, as no book has ever done since’). But if it’s not a children’s tale, Tarka hardly conforms to the norms of adult fiction, either. Since the time of Jane Austen at least, our idea of the novel has been bound up with that of the self-aware, self-reflecting human consciousness – the sensitive individual looking before and after, questioning her own motives, growing through moral experience. And negotiating that other world, the social world of class and money, with all its tricky nuances. By contrast, Tarka’s world is all appetite and instinct, with no room for introspection or moral discovery. The life of a wild animal is literally one thing after another, and markedly un-nuanced. To find a parallel in fiction you’d have to go to opposite ends of the literary spectrum – to the pulpiest sort of action thriller or something all French and experimental by Robbe-Grillet. To tell the truth, it’s not even one thing after another, this wild animal life – it’s the same bloody thing, over and over and over. There’s a short passage in Tarka that pretty well sums up the book:While the pallor of the day was fading off the snow a skein of great white birds, flying with arched wings and long stretched necks, appeared with a measured beat of pinions from the north. Hompa, hompa, hompa, high in the cold air . . . The beams of the lighthouse spread like the wings of a starfly above the level and sombre sands. Across the dark ridge of the Sharshook a crooked line of lamps winked below the hill.

Dog eat bird eat rat eat fish eat fish: this is Williamson’s great theme and one that seems to inspire a keen ambivalence. Part of him, I suspect, thinks we should all just get on and lead a jolly murderous life, like his Nietzschean über-rat, while another part is wincingly aware of the pain in the world and yearns for some sort of Buddhist or Christian release. Everywhere in his work you’ll find this divided sympathy, for the prey as for the predator. It comes out strongly and for many people uncomfortably whenever Williamson writes about hunting – he identifies with the terror of the hunted stag or otter, but also with the fierce glee of the hunter and with a mystical idea of life replenished through death. For Williamson, you feel, the hunt is less a form of pest control than the ritual expression of a cosmic principle – a code of death that can be read in the heavens as on earth:[Tarka] caught a black and yellow eel-like fish, whose round sucker-mouth was fastened to the side of a trout . . . The sickly trout, which had been dying for days with the lamprey fastened to it, floated down the stream; it had been a cannibal trout and had eaten more than fifty times its own weight of smaller trout . . . A rat ate the body the next day, and Old Nog [the heron] speared and swallowed the rat three nights later. The rat had lived a jolly and murderous life, and died before it could fear.

It’s rather hard to know what to say about a passage like that – except that it’s not exactly Springwatch (‘Now over to Kate for the latest on those false star dwarfs . . .’). Though not always even a good writer, Williamson has the power to astonish that we normally associate only with the great artists. If you have the patience, and the stomach, you’ll find passages of like power scattered throughout his works, even the mediocre or downright bad ones, not to mention those that are ideologically beyond anyone’s pale. The question that most fascinates – and troubles – is how far Williamson’s later views can be seen as a mad aberration, and how far they reflect toxins already latent in his thought. A ‘religion of nature’ can seem an attractive, life-affirming thing, but in practice it tends to go a bit like this: worship of nature shades into worship of vitality, which shades into worship of power, which shades into worship of cruelty. The Tarka world is one of pristine energies and a fierce purity of purpose that sits uneasily with the benign muddle of a democracy. Disconcertingly, it’s the strong and radiant things in his work, as much as the weak and silly ones, that show how Williamson could be drawn to some form of fascism.By night the great stars flickered as with falcon wings, the watchful and glittering hosts of creation. The moon arose in its orbit, white and cold, awaiting through the ages the swoop of a new sun, the shock of starry talons to shatter the icicle spirit in a rain of fire. In the south strode Orion the Hunter, with Sirius the Dogstar baying green fire at his heels. At midnight Hunter and Hound were rushing bright in a glacial wind, hunting the false star dwarfs of burnt-out suns, who had turned back into Darkness again.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 35 © Jonathan Law 2012

About the contributor

Jonathan Law is a writer and editor of reference books and a director of Market House Books Ltd. In The Dabbler Jonathan delves even deeper into the strange mind of Henry Williamson in some follow-up articles.