Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, Robert Louis Stevenson’s account of his walk through the mountains in 1878, was my mother’s favourite book, which automatically made it one of mine. The brown cover of her 1906 edition is faded with fingering, its pages frayed and loose from her rereadings. Many of the fictional characters who figured largest in my childhood were full of machismo, because they were in books filched from my brothers. Stevenson’s donkey Modestine, on the other hand – ‘patient, elegant, the colour of an ideal mouse’ – was a comforting antidote, domestic and affectionate for all her perceived obstinacy. But Stevenson himself fitted my expectations of a dashing young adventurer, setting off alone in a foreign land. His Travels with a Donkey filled me with romantic ideas – the independence of the lone explorer; the rapport with natural beauty; the almost sacred duty to record experiences.

Though I didn’t know it when I first read it, Stevenson had started a new tradition in travel literature – he had set out on his journey in order to write a book about it. (He had a pressing need to earn money.) Now the genre has been badly abused, and anyone tempted to find a new gimmick (such as walking with a fridge) should go back to Travels with a Donkey and see how he did it – properly. Stevenson’s account of his chequered relationship with Modestine the donkey is both pithy – ‘she tried, as was her invariable habit, to enter every house and every courtyard . . . and, encumbered as I was, without a hand to help myself, no words can render an idea of my difficulties’ – and poignant: on the same page he strikes Modestine and then almost weeps with remorse. His encounters with the locals are recalled with a mixture of dry humour and sensitivity, from profound debates with the monks at the abbey of Notre Dame des Neiges to absurd exchanges with villagers near Sagnerousse who are reluctant to hel

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inTravels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, Robert Louis Stevenson’s account of his walk through the mountains in 1878, was my mother’s favourite book, which automatically made it one of mine. The brown cover of her 1906 edition is faded with fingering, its pages frayed and loose from her rereadings. Many of the fictional characters who figured largest in my childhood were full of machismo, because they were in books filched from my brothers. Stevenson’s donkey Modestine, on the other hand – ‘patient, elegant, the colour of an ideal mouse’ – was a comforting antidote, domestic and affectionate for all her perceived obstinacy. But Stevenson himself fitted my expectations of a dashing young adventurer, setting off alone in a foreign land. His Travels with a Donkey filled me with romantic ideas – the independence of the lone explorer; the rapport with natural beauty; the almost sacred duty to record experiences.

Though I didn’t know it when I first read it, Stevenson had started a new tradition in travel literature – he had set out on his journey in order to write a book about it. (He had a pressing need to earn money.) Now the genre has been badly abused, and anyone tempted to find a new gimmick (such as walking with a fridge) should go back to Travels with a Donkey and see how he did it – properly. Stevenson’s account of his chequered relationship with Modestine the donkey is both pithy – ‘she tried, as was her invariable habit, to enter every house and every courtyard . . . and, encumbered as I was, without a hand to help myself, no words can render an idea of my difficulties’ – and poignant: on the same page he strikes Modestine and then almost weeps with remorse. His encounters with the locals are recalled with a mixture of dry humour and sensitivity, from profound debates with the monks at the abbey of Notre Dame des Neiges to absurd exchanges with villagers near Sagnerousse who are reluctant to help when he is lost in the dark. But best of all are his descriptions of landscape – so vivid, and so personal, I could feel them myself. Here he is at sunrise:soon there was a broad streak of orange melting into gold along the mountain-tops of Vivarais. A solemn glee possessed my mind at this gradual and lovely coming in of the day . . . Nothing had altered but the light, and that, indeed, shed over all a spirit of life and of breathing peace, and moved me to a strange exhilaration.To be able to write like this, to experience a scene and to recreate it, was all I wanted to do, I decided, when I first read the book. This was what it was like to be freelance, a journalist, a travel writer. And that is what I became. So when, a few years ago, I and Molly, a friend living in France, discovered that there was now an official signposted footpath along the route that Stevenson took through the Cévennes, the chance to follow literally in his footsteps was thrilling. We decided we should do it just as Stevenson had. Of course this is not actually possible now, thank goodness. L’Association du Chemin de Robert Louis Stevenson, formed in the early 1990s to exploit the tourist potential of Stevenson’s journey from Le Monastier to St Jean du Gard, makes things much easier. We didn’t have to buy our donkey and we didn’t need to camp out, since we could choose from a list of donkey bed-and-breakfasts, where the donkey would be tended to and so would we. This was obviously, in practical terms, much more enticing, though reading again the list of supplies that Stevenson packed made me hanker (fleetingly) after the simpler life:

a revolver, a little spirit-lamp and pan, a lantern and some halfpenny candles, a jack-knife and a large leather flask . . . The permanent larder was represented by cakes of chocolate and tins of Bologna sausage . . . For more immediate needs, I took a leg of cold mutton, a bottle of Beaujolais, an empty bottle to carry milk, an egg-beater and a considerable quantity of black bread and white.Curiously, apart from the ‘hard fish and omelette’ which was standard fare at many inns, as Stevenson comments when he stops in St Nicholas le Bouchet, this is almost his only reference to food. Our own preoccupations were very different: anticipation of the next meal or deconstruction of the last was what kept us going in difficult times. And there were many of those, right from the start. We had a disastrous first trip – possibly because the only preparation I had made was to reread Travels with a Donkey on Eurostar on my way to Pradelles where we were to hire our donkey, and possibly because we attempted to use Stevenson as a guidebook. After all, the reason there is a Trail now is because he was so precise about places. So when, resting in a grassy lane outside Langogne, I read aloud to Molly Stevenson’s lines about the distance to our destination of Cheylard l’Évêque – ‘A man, I was told, should walk there in an hour and a half, and I thought it scarce too ambitious that a man encumbered with a donkey might cover the same distance in four hours’ – it provided crucial, but utterly false, encouragement when we were at a low ebb. (Our donkey Noisette was even more recalcitrant than Modestine – and, amazingly, even slower than we were.) I should have reminded myself of the next bit: he didn’t in fact make it that day. We returned the following year, better prepared and accompanied by a different donkey, but always with Travels with a Donkey in hand. This time we started the journey properly, where Stevenson did, at Le Monastier. We compared our impressions of the town with his – even then he was lamenting the passing of its ‘dancing days’, though he also wrote of its fifty wine shops and chatty lacemakers: it is considerably less lively now. We crossed the little river he crossed – now there is a bridge instead of a ford – and walked up what must have been exactly the same path into the woods as he did. We descended into Goudet and saw the castle on the opposite hill, just as he saw it – and crossed the river he describes so engagingly: ‘Above and below, you may hear it wimpling over the stone, an amiable stripling of a river, which it seems absurd to call the Loire.’ My paperback copy, bought specially for squashing into a pannier, is marked in the margins with notes like ‘Us too!’ Though we were a pair, we often felt the solitude as he did: on many days we saw no one on the Trail. When we did, we were objects of real curiosity, with our donkey, just as he was then. In truth, of course, our experience was utterly different. Stevenson was venturing into wild country with only a rough idea of direction, along tracks which sometimes diverged into three or four different ways, with no clue as to the right one. We, though, were constantly guided by the red-and-white markings of the grandes randonnées, walking within safe boundaries, as along an unroofed corridor with unseen walls. With such twenty-first-century support, it was sometimes difficult to capture the spirit of proper adventure he must have had. But the adventure was only part of it. What I discovered on my adult rereadings was that there were two relationships in the book: one with Modestine, and the other, only alluded to but constantly present, with Stevenson’s absent lover. Two years before, at the artists’ colony of Grez, he had met Fanny Osbourne, a spirited American woman ten years older, who was good at shooting, had two children and, more to the point, was still married. In August 1878 she had gone back to California to visit her husband, ultimately to get a divorce, but when Stevenson was wandering around the Cévennes a month later he didn’t know this would be the outcome. In the chapter ‘A Night among the Pines’ he refers to what must have been his continuing preoccupation – one that might strike a chord with any reader:

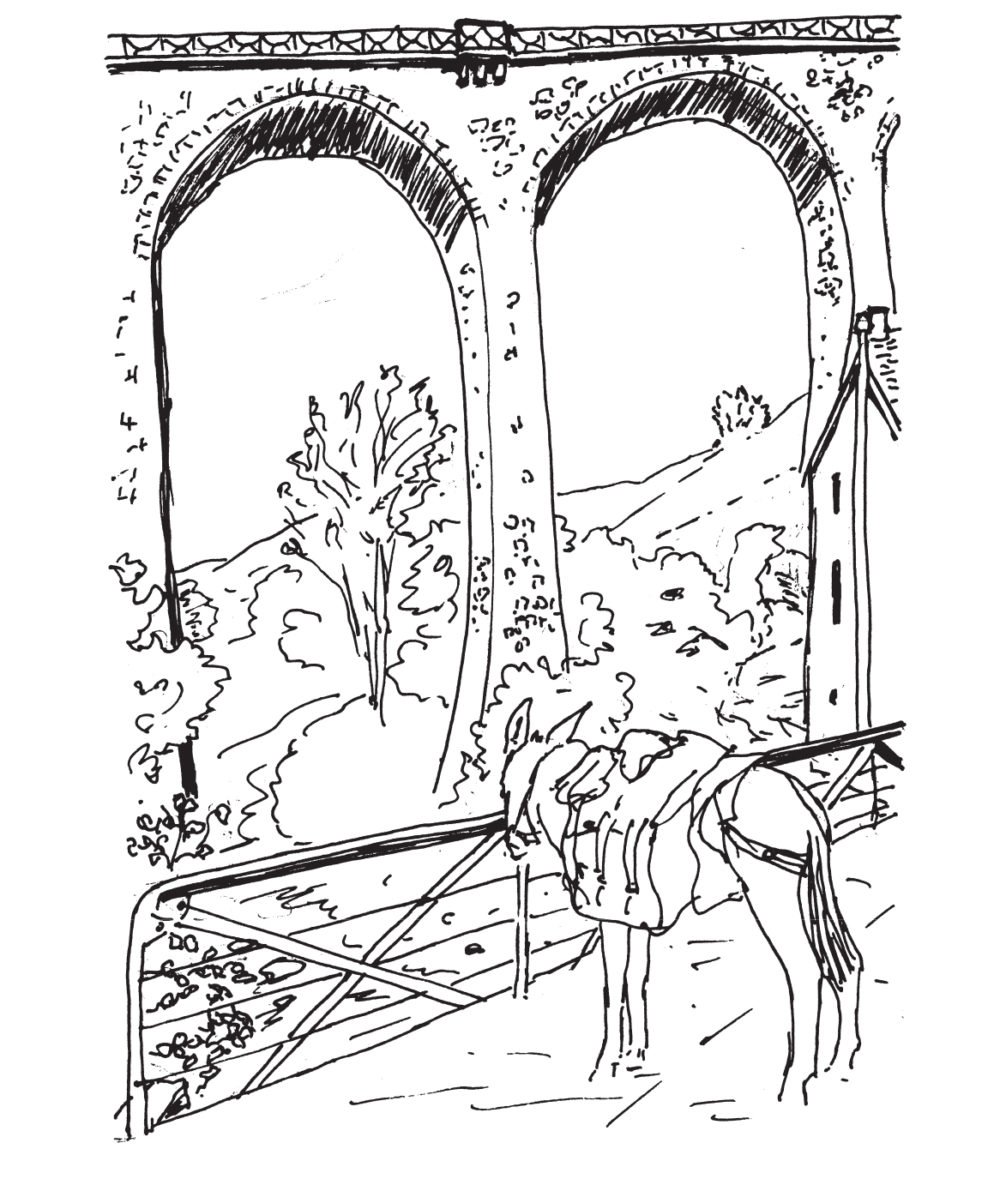

And yet even while I was exulting in my solitude I became aware of a strange lack. I wished a companion to lie near me in the starlight, silent and not moving but ever within touch. For there is a fellowship more quiet than solitude, and which, rightly understood, is solitude made perfect. And to live out of doors with the woman a man loves is of all lives the most complete and free.Everywhere on our journey we took pleasure in making connections, sometimes staying in the same places as Stevenson did. At the Hotel des Cévennes in Pont le Montvert, where we ate a mouthwatering meal, Stevenson, we discovered, had been more concerned with the ‘cow-like charms’ of Clarisse the waitress (perhaps his heart was not so broken after all). In Chasseradès he wrote that ‘the company in the inn . . . were all men employed in survey for one of the projected railways’. We saw the results – a great viaduct stalking across the valley, gigantic arches framing a deeply blue sky, with a train making its cautious way across. When we mounted the hill rising out of Goudet quite easily (unusual for us), we felt briefly smug because Stevenson had described it as ‘interminable’. We heartily agreed with him about Cheylard l’Évêque which he – and we – had found difficult to reach: ‘Candidly, it seemed little worthy of all this searching.’ Above all, we shared his delight in the splendour of the scenery, trying to identify the views he had seen. We were sure we’d found the viewpoint near Cassagnas about which he wrote: ‘Peak upon peak, chain upon chain of hills ran surging southwards, channelled and sculptured by the winter streams, feathered from head to foot with chestnuts and here and there breaking out into a coronal of cliffs.’ I thought of my mother and tried to see it all through her eyes, imagining how she would have marvelled at being able to follow in Stevenson’s footsteps; I felt, in a way, as though I was following in hers. When he reached St Jean du Gard, Stevenson sold Modestine in a great hurry and scurried off to Alès in a carriage, to see if there were any letters waiting for him. The journey had taken him, a consumptive invalid, eleven days; it took us, two healthy females, seventeen days and several trips. I felt respect for his stamina, but what I valued most was his recording of experiences and emotions that can be shared by his readers, whether they follow in his footsteps or not. The most-quoted lines from the book are: ‘For my part I travel not to go anywhere but to go: I travel for travel’s sake.’ In the journal he kept, on which the book is based, there is the additional sentence: ‘And to write about it afterwards if only the public will be so condescending as to read.’ They did, and they still do. For us, in the end, Travels with a Donkey proved better than a guidebook: it was a companion on the journey.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 14 © Hilary Macaskill 2007

About the contributor

Hilary Macaskill’s account of her travels, Downhill All the Way: Walking with Donkeys on the Stevenson Trail, written with and illustrated by Molly Wood, was published last year.