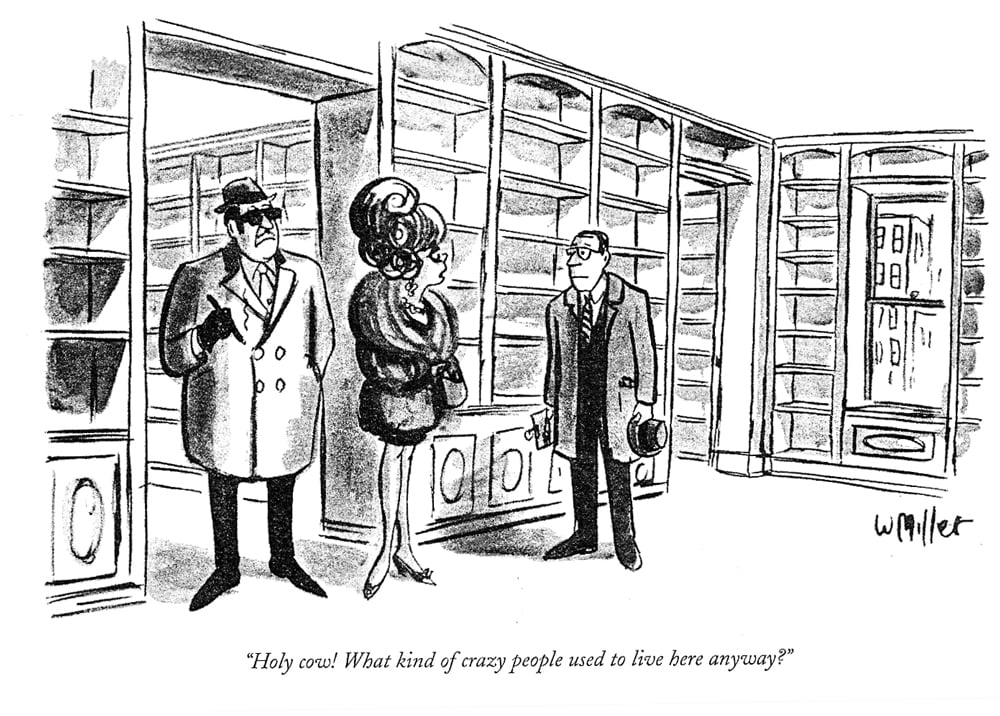

Let’s begin with a brief quiz. Have you ever arrived home, triumphant with glee over your latest bookshop find, only to discover that you already have the book you just purchased? Have you ever attempted to bring home unobserved a stack of newly purchased books, and thus avoid the censorious lift of the eyebrows of loved ones which so often greets your latest acquisitions? Have you ever begun reading a book you’ve been looking forward to for years, even decades, only to discover your own notes in the margins? (If so, you are a bibliolathas.) Are you on first-name terms with the staff of three bookshops or more? Have you ever had to reinforce a sagging floor because of the weight of your books? Have you ever had to add a room on to your home or move to a larger one to accommodate them?

If you can answer yes to at least three of these questions you will understand why book collecting is the only hobby to have a disease named after it: bibliomania. You will also appreciate the allure of a title like The Anatomy of Bibliomania.

My discovery of this treatise by Holbrook Jackson was not serendipitous, for in a bookshop, as every bibliophile knows, there are no accidents. There is only Destiny. It sat on the dusty shelf at eye-level: a siren song in two glorious volumes, bound in red buckram, the 1931 Soncino Press first edition, number 537 from a limited edition of 1,000 copies (alas, not one of the 48 copies on hand-made paper), 8vo, gilt top edges, minor fading to spines, no foxing, tanning or bumping to extremities, text block clean and tight, hinges strong, no previous owner’s inscription or bookplate.

Modelled on Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy, both in format and in its deliciously pedantic early-seventeenth-century turn of phrase, it is an exhaustive pastiche of everything ever written that’s worth saying (as well as a few things that might have been better left unsaid) about the nature and allure of books and t

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inLet’s begin with a brief quiz. Have you ever arrived home, triumphant with glee over your latest bookshop find, only to discover that you already have the book you just purchased? Have you ever attempted to bring home unobserved a stack of newly purchased books, and thus avoid the censorious lift of the eyebrows of loved ones which so often greets your latest acquisitions? Have you ever begun reading a book you’ve been looking forward to for years, even decades, only to discover your own notes in the margins? (If so, you are a bibliolathas.) Are you on first-name terms with the staff of three bookshops or more? Have you ever had to reinforce a sagging floor because of the weight of your books? Have you ever had to add a room on to your home or move to a larger one to accommodate them?

If you can answer yes to at least three of these questions you will understand why book collecting is the only hobby to have a disease named after it: bibliomania. You will also appreciate the allure of a title like The Anatomy of Bibliomania. My discovery of this treatise by Holbrook Jackson was not serendipitous, for in a bookshop, as every bibliophile knows, there are no accidents. There is only Destiny. It sat on the dusty shelf at eye-level: a siren song in two glorious volumes, bound in red buckram, the 1931 Soncino Press first edition, number 537 from a limited edition of 1,000 copies (alas, not one of the 48 copies on hand-made paper), 8vo, gilt top edges, minor fading to spines, no foxing, tanning or bumping to extremities, text block clean and tight, hinges strong, no previous owner’s inscription or bookplate. Modelled on Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy, both in format and in its deliciously pedantic early-seventeenth-century turn of phrase, it is an exhaustive pastiche of everything ever written that’s worth saying (as well as a few things that might have been better left unsaid) about the nature and allure of books and the characteristics, not always flattering, of the people who treasure them. Jackson wrote dozens of books, many on bookish subjects (see SF no. 16), but this surely is his magnum opus. A sampling of the Table of Contents will illustrate why the whole reads like the bibliophilic equivalent of Aladdin’s cave: Of Letter Ferrets and Book Sots; A Cure for Pedantry; Of the Bibliophagi or Bookeaters (these are, mostly, metaphors, though the legendary bookdealer A. S. W. Rosenbach attributed the scarcity of first editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to their having been eaten by children); Liberating the Soul of Man; Reading at the Toilet (a fine bit of bathos, this); The Book-borrower and All Manner of Biblioklepts (a pervasive and insuperable strain on countless friendships); Defence of Fine Bindings (as if one were needed); Book Ghouls (!); and On Parting with Books (material to make even a stout heart quail). Having whetted our appetite, we turn the page to discover ‘The Author to the Reader’, one of those lengthy, discursive and often unnecessary prefaces one is inclined to skip, but then we read this:Gentle Reader, I presume thou wilt be very inquisitive to know what antic or personate actor it is that so insolently intrudes upon this common theatre to the world’s view, arrogating, as you will soon find, another man’s style and method: whence he is, why he does it, and what he has to say. ’Tis a proper attitude, and the questions clear and reasonable in themselves, but I owe thee no answer, for if the contents please thee ’tis well; if they be useful, ’tis an added value; if neither, pass on . . .Pass on? ‘Arrogate, Sir!’ say I. This is an antic and personate actor I can cosy up to, and for the next 600 pages the tone never falters; nor does Jackson’s formidable vocabulary. How often do we confront words like operose, fardel, erewhile, dizzards, solatium, welter, collectanca, peradventure, belike and (my favourite) the musical gallimaufry? Yet all these are to be found just in the preface. Jackson’s ardent pedantry lends itself as happily to the joy of books as it does to his take-no-prisoners attacks on the creatures who misuse them or, worse still, those who pretend to a familiarity with a book they have not read, for whom he reserves a special venom. These are the book pscittacists (now there’s a word for you), the people who repeat, parrot-like, what they have heard others say of books or what they have gleaned from dust-wrapper blurbs and reviews. The range and depth of Jackson’s own reading and his facility for unearthing the most apropos quotations are astonishing. He begins his rant, ‘Vain and Pedantic Reading Condemned’, by marshalling Crabbe, Montaigne and Samuel Butler.

There are others . . . that eschew all reading except for vainglory, Who read huge works to boast what ye have read, to disport their second-hand stock of ideas and information, for a fading greedy glory, to cousin and delude the foolish world; to peacock themselves at large, like Aesop’s daw in borrowed feathers. Among them are others who Affect all books of past and modern ages,/ But read no further than the title-pages.One thinks of Finnegans Wake or the novels of Thomas Pynchon. I know there are people who have actually made it through Finnegans Wake, and even liked it, but for everyone who has said so honestly there are hundreds who have told a whopping fib. As for Pynchon, I myself trudged to the end of Mason and Dixon because a friend gave me a copy, raved about it, and truly had read it himself and loved it. It was a journey more arduous than that of the intrepid surveyors through storm, swamp and wilderness. Never again. Life is short, and there are limits to friendship. Still, as Pope wrote, I concede that judgements are like watches. None go just alike yet each believes his own. Chock-a-block with quotations, aphorisms and anecdotes, all lovingly and meticulously footnoted, The Anatomy of Bibliomania is a treasure-trove of whimsy, revelry, vituperative eloquence and the disconcertingly weird. There is Edward Gibbon, who swapped a copy of his Decline and Fall for a hogshead of Madeira. There is the man who wanted to perform a Christian marriage for an aboriginal couple in Central America, but as they knew no English and he had no bible, he officiated at their nuptials by reading aloud a chapter from Tristram Shandy. There is the story of a Dr O’Rell, who claimed to have discovered the cause of the book-lover’s disease in a bacillus librorum, which when injected into the femoral artery of a cat caused it to eat a copy of Rabelais. Then there are the aforementioned book ghouls, the people who destroy books to turn them into storage boxes for cigars, chocolates and notepaper. They are no better than body-snatchers, desecrators of the temple, vain, tawdry, callous, whether sellers of such monuments of destruction or buyers of them, biblioclasts and dolts to boot, necrofils of a sort; beside them the naïfs who use dummy books are princes of intelligence, nay bibliophiles of the blood, though dizzards . . . Happily, Jackson did not live to see Reader’s Digest Condensed Books. They would no doubt have reminded him of Robert Burton, who wrote in a far coarser context that starving dogs will eat dirty puddings. Many years ago, before my own bibliophilic illness began seriously to take hold, I kept my books in a small room about six feet wide and perhaps twelve feet long, the two longer walls lined with bookshelves, leaving room for a floor lamp and a comfortable chair in the centre. Soon I began double shelving, removed the chair and placed a doublewidth bookcase down the centre of the room. This left two passageways that were each perhaps nine inches wide. Thus, if I wanted a book I had to move into the room sideways, like a crab, and if I discovered the book I wanted was behind me, I had to back out and turn around. Books near the floor were more problematic. There was no room to crouch, so I had to lie down and slink in, caterpillar-style. When a friend from London, herself a book dealer, saw my little room, there was, as the novelists say, a pregnant pause. After a deep breath, her eyes grew wider and her face contorted into something between a smile and a grimace. ‘Oh, you’ve got it bad,’ she said. And so, Gentle Reader, if you have yourself experienced one of those moments – and if you’re reading this you almost certainly have – you will find The Anatomy of Bibliomania the most congenial and empathetic of bedside companions.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 68 © Richard Platt 2020

About the contributor

As he lives a rich fantasy life, Richard Platt is attempting to pare down his library and resist the temptation of new acquisitions, the exception, of course, being Slightly Foxed Editions.