When I think back to that first visit of mine to Estonia in 1988, I see muted, metallic-grey tones of fog and sea; above all I remember a sense of wonder that I was finally on my way to my mother’s homeland. Ingrid was 17 when, stateless and displaced, she arrived in England in 1947, having fled westwards from the Baltic ahead of Stalin’s advancing Red Army. She had not been back to her native land since. Now, half a century later, I was sailing to the Estonian capital of Tallinn from Helsinki – a three-hour journey by ferry across the Gulf of Finland. The Independent Magazine had asked me to report on Moscow’s waning power in the Soviet Baltic. A hammer and sickle flapped red from the ship’s stern as we set sail. The air was pungent with engine oil as I walked towards the stern and watched Helsinki’s Eastern Orthodox cathedral dwindle to a dot.

On the flight over to Helsinki from London I had read a novel by the Estonian writer Jaan Kross, Four Monologues on St George. It investigates the life of the Tallinn-born artist Michel Sittow, who had worked as court painter to Queen Isabella of Spain in the late fifteenth century, and it had been published in Moscow in 1982 in a translation by Robert Dalglish. I did not know it then, but Kross had written sixteen other semi-factual historical novels set in Estonia under the Swedish, Danish, Russian and Nazi occupations. The novels all sought to outwit Soviet censorship – ‘writing between the lines’, Kross called it – and use history as a way to restore Estonia’s national memory under dictatorship and confirm the country’s place as Europe’s ultimate East-West borderland.

In the centuries before Kross, Western travellers had marvelled at the untranslatable names and the ‘exotic’ strangeness of sea-girt Estonia. In 1839 Lady Elizabeth Eastlake (later notorious for her hostile review of Jane Eyre in the Quarterly Review) had travelled by sledge acro

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhen I think back to that first visit of mine to Estonia in 1988, I see muted, metallic-grey tones of fog and sea; above all I remember a sense of wonder that I was finally on my way to my mother’s homeland. Ingrid was 17 when, stateless and displaced, she arrived in England in 1947, having fled westwards from the Baltic ahead of Stalin’s advancing Red Army. She had not been back to her native land since. Now, half a century later, I was sailing to the Estonian capital of Tallinn from Helsinki – a three-hour journey by ferry across the Gulf of Finland. The Independent Magazine had asked me to report on Moscow’s waning power in the Soviet Baltic. A hammer and sickle flapped red from the ship’s stern as we set sail. The air was pungent with engine oil as I walked towards the stern and watched Helsinki’s Eastern Orthodox cathedral dwindle to a dot.

On the flight over to Helsinki from London I had read a novel by the Estonian writer Jaan Kross, Four Monologues on St George. It investigates the life of the Tallinn-born artist Michel Sittow, who had worked as court painter to Queen Isabella of Spain in the late fifteenth century, and it had been published in Moscow in 1982 in a translation by Robert Dalglish. I did not know it then, but Kross had written sixteen other semi-factual historical novels set in Estonia under the Swedish, Danish, Russian and Nazi occupations. The novels all sought to outwit Soviet censorship – ‘writing between the lines’, Kross called it – and use history as a way to restore Estonia’s national memory under dictatorship and confirm the country’s place as Europe’s ultimate East-West borderland. In the centuries before Kross, Western travellers had marvelled at the untranslatable names and the ‘exotic’ strangeness of sea-girt Estonia. In 1839 Lady Elizabeth Eastlake (later notorious for her hostile review of Jane Eyre in the Quarterly Review) had travelled by sledge across the country to a chorus of howling wolves. Estonia was viewed in Eastlake’s day (and to an extent, it still is) as a Ruritanian outpost as remote and exotic as the fictional Syldavia of the Tintin books. (The eye-patch-wearing pilot Piotr Skut of Tintin’s Flight 714 to Sydney actually is Estonian.) In Kross’s view, foreign deprecations of the Baltic as a notional ‘Dracula-Land’ on the fringes of Eurasia are mostly born of ignorance.*

A Russian voice over the ship’s tannoy cautioned us to put our watches forward by an hour in anticipation of the Soviet time zone. Presently Tallinn’s coastline came into view through the September haze. The maternal city glimmered as an arrangement of Orthodox onion cupolas and Lutheran church knitting-needle spires. With a crowd of Finns I disembarked and made my way across a rain-slicked quay. The customs shed was filled with trestle tables where uniformed officials were busy opening and searching luggage. A sign announced: WELCOME TO SOVIET TALLINN, but the customs man was not too welcoming. ‘How long in Tallinn do you stay?’ – spoken as to an idiot. ‘A week.’ He looked at my passport. ‘Purpose of visit?’ ‘Tourism,’ I lied. Leaving the harbour, I walked in the direction of the Soviet high-rise Hotel Viru, where a room had been booked for me. From the restaurant on the twenty-second floor I was able to survey Tallinn at night. Through the plate-glass windows a red star fizzed over the central railway station and the toy fort-like turrets of the medieval castles described by Kross in Four Monologues on St George. Kross did not come to prominence in the English-speaking world until 1992, when his fifth novel The Czar’s Madman appeared in translation. Unquestionably this is his masterpiece; narrated through a mosaic of journals, diary entries, memoranda and other writings, the novel has the grand sweep and pleasurable density of Tolstoy. ‘Kross is a great writer in the old, grand style,’ Doris Lessing wrote in the Spectator in 2003. The novel concerns the alleged insanity of a Baltic-German aristocrat, Timotheus von Bock, who was stationed in 1820s Livonia (present-day Estonia and Latvia) in the period just after War and Peace. Baron von Bock has the temerity to send Tsar Alexander I a dangerously frank list of proposals for constitutional reform and upbraids him for his maltreatment of serfs. For this reckless and solitary act of rebellion the Baron is imprisoned for nine years in the fortress of Schlüsselburg east of St Petersburg, and then released into house arrest on his estate at Voisiku in present-day Estonia. Coincidentally or not, Kross had served almost the same term in the Gulag. For eight years between 1946 and 1954 he slaved in a coalmine near the feared Vorkuta camp west of the Urals and at a brickworks in the Krasnoyarsk region. On its publication in Soviet Tallinn in 1978, Keisri Hull (literally, ‘The Emperor’s Crazy’) sold an impressive 32,000 copies. Kross’s paradox – is von Bock mad or does his truth-telling illuminate the ‘insane’ world in which he lives? – appeared to mirror the Brezhnevian psychiatric asylums and the misuse of medical diagnoses in the USSR to silence dissidents. It opens in 1827 on von Bock’s release from Schlüsselburg; all his teeth have been knocked out by janitors and he cuts a pitiful figure as he enters house arrest on his Estonian estate. A decade earlier in Estonia, his egalitarian principles had led him to educate and marry a local-born chambermaid called Eeva Mattik (she had been released from serfdom for the price of four English hounds) but he was no sooner married than, in 1818, the Tsar imprisoned him. Eeva’s brother, Jakob Mattik, a teacher, has meanwhile discovered a draft of the Baron’s memorandum to the Tsar and rescued from the fire a sheaf of his letters and a boxful of official papers. Though yellowing with age, the material serves Jakob as the basis for his own meditations on Tsarist repression and the nature of the Baron’s imputed ‘madness’. The Czar’s Madman, a work of Tristram Shandy-like digressions and reflections on the nature of literary ‘truth’, is narrated by Jakob in the form of a journal that spans twenty-odd years up to the Baron’s mysterious death (was he murdered or did he take his own life?) in 1836. Into his journal Jakob incorporates extracts from the inflammatory memorandum and seeks to reconstruct the events leading up to the Baron’s arrest and incarceration. He writes partly in German. Estonians who had managed to escape serfdom could only do so if they spoke German, or Low German, a language considered at that time second only to ancient Greek. Jakob’s rise from ‘peasant stock’ to become a man who is able to identify a Claude Lorrain engraving or a Schubert symphony was extraordinary but not without precedent in the Baltic under the Tsars. A century earlier, in 1742, a freed African slave named Abram Gannibal had been appointed Tallinn’s military commander by Peter the Great’s daughter Elizabeth, Empress of Russia. Gannibal happened to be the maternal great grandfather of Alexander Pushkin. Kross had long wanted to write the story of the Cameroon-born Gannibal; but, it seems, he decided instead to chronicle that of von Bock. The Czar’s Madman is brocaded with period detail. The drawingrooms where people read literature in one corner and play chess in another are familiar to us from Russian literature. So, too, are the many visitors to von Bock’s estate who come in from the snow for glasses of tea in the long wintry nights. Jakob’s affinity with Baltic nature (what he calls his ‘swaying, separate world’) adds to the novel’s vivid immediacy of detail:We are surrounded by the quiet waters of the creek and the green curtain of reeds. Now and again a perch jumps, or a mallard takes off, slapping the water. The reeds rustle. Some stalks bend in curious ways. As you get closer, a single reed among millions becomes astoundingly unique: with its long narrow leaves, its dome-like top of hairy, brownish-violet spikelets, it is like a building, a flowering world of its own.In spite of the climate of suspicion in mid-1970s Moscow, the Soviet authorities had been only too happy to help Kross research The Czar’s Madman. It may be that von Bock (his name means ‘stubborn’) was viewed favourably by the Soviet censors as a social Utopian and luminary of the German Enlightenment. The real-life Timotheus von Bock had been associated with the Decembrist revolt of 1825, when young Russian aristocrats rose against the Tsarist autocracy. When The Czar’s Madman finally appeared in Russian translation in 1985, Kross was relieved to find that it contained few distortions or deletions, despite the covert links he had made between Tsarist oppression and Soviet oppression. The novel could be read as an allegory about totalitarian communism but, equally, it could be an allegory about an absolutist nightmare anywhere. Under house arrest von Bock, a prototype prisoner of conscience, has to deal with spies and informers, some with a worse conscience than others (one invites him to write his own surveillance reports for the authorities). But he refuses to be broken by either violence or bribery.

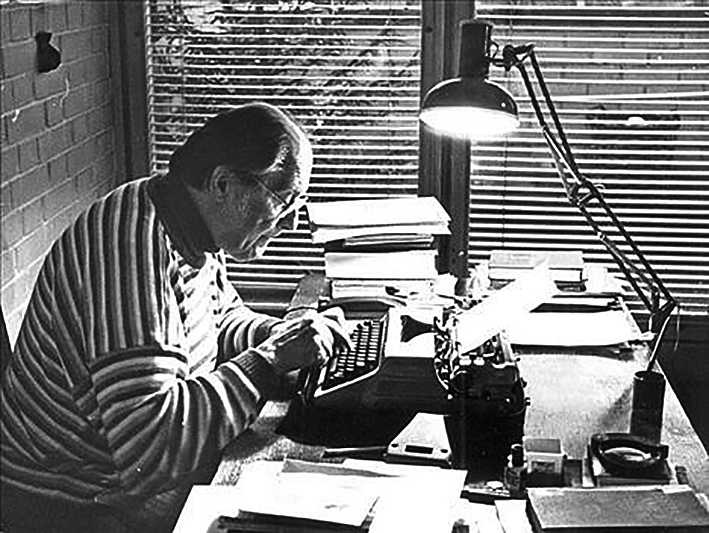

*

My article on the Baltic under Soviet communism had scarcely appeared in the Independent than, in November 1988, Estonia proclaimed its sovereignty. Suddenly the entire USSR was a sandpile ready to slide. On 6 November 1991 the Russian President Boris Yeltsin (reportedly inflamed by vodka) officially terminated the USSR’s existence when he banned the Communist Party within Russia. Estonia was now free and Red Tallinn had gone before I knew it. The years passed. I sought out other books by Kross. His twelfth novel, Professor Martens’ Departure (1984), concerns a hapless Baltic expert employed by Tsar Nicholas II to collate treatises; again it unfolds as an exercise in paradox and ambiguity. It was not until 2003 that I finally met Kross. At 83, he was frail and had recently suffered a stroke. He was living with his third wife, the poet and children’s writer Ellen Niit, on the fifth floor of the Soviet-era Writers’ House in Tallinn’s old quarter. In him I found the modesty of the true writer, a sorrowful yet slightly mischievous presence. He said he was ‘itching’ to write another novel but was content for the moment to work on his memoirs. By now he had been translated into twenty three languages; in 1992 he was given ‘advance warning’ that he would win the Nobel Prize for Literature and told to stay by the phone. Nadine Gordimer won that year. Kross never did. Kross’s later short stories, collected in English in 1995 under the title The Conspiracy, recount attempts by Estonians to flee across the Gulf of Finland to Helsinki during the Nazi occupation or their deportation to the Gulag by the Soviets. Understandably, Kross did not begin to describe his Gulag years in print until the advent of Gorbachev’s perestroika in the mid-1980s. Even so, there is surprisingly little bleakness in his prison tales. Kross writes about his incarceration under dictatorship with a poignancy devoid of anger. All his work is the product of a refined and subtly ironic mind, but The Czar’s Madman ranks with Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard as an historical novel of timeless importance. Jaan Kross died, at the age of 87, in Tallinn in 2007. He is one of Europe’s most revered writers and I would recommend his books unreservedly.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 67 © Ian Thomson 2020

About the contributor

Ian Thomson is the author of Primo Levi: The Elements of a Life, and two prize-winning works of reportage, Bonjour Blanc: A Journey through Haiti and The Dead Yard: Tales of Modern Jamaica. His most recent book, Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Journey Without End, was published in 2018.