I came to Winchester Cathedral to pay homage to one of my favourite authors. Not Jane Austen, though. I enjoy her work, but she doesn’t need my support. When I arrive, a bevy of young admirers is already crouching over her foot-worn monument, striking poses and taking selfies with their smartphones. No, I have come to find the final resting place of Izaak Walton, author of The Compleat Angler.

I am directed to a tiny side chapel in the south transept – called Prior Silkstede’s Chapel – where I find the writer pressed beneath a thick slab of black marble before the altar. Walton died on 15 December 1683, aged 90, and there is a pious, rather conventional poem carved on the stone, ending with the Latin tag: Votis modestis sic flerunt liberi, which I translate as ‘This modest prayer his weeping children lament’, revealing, perhaps, my lack of a classical education.

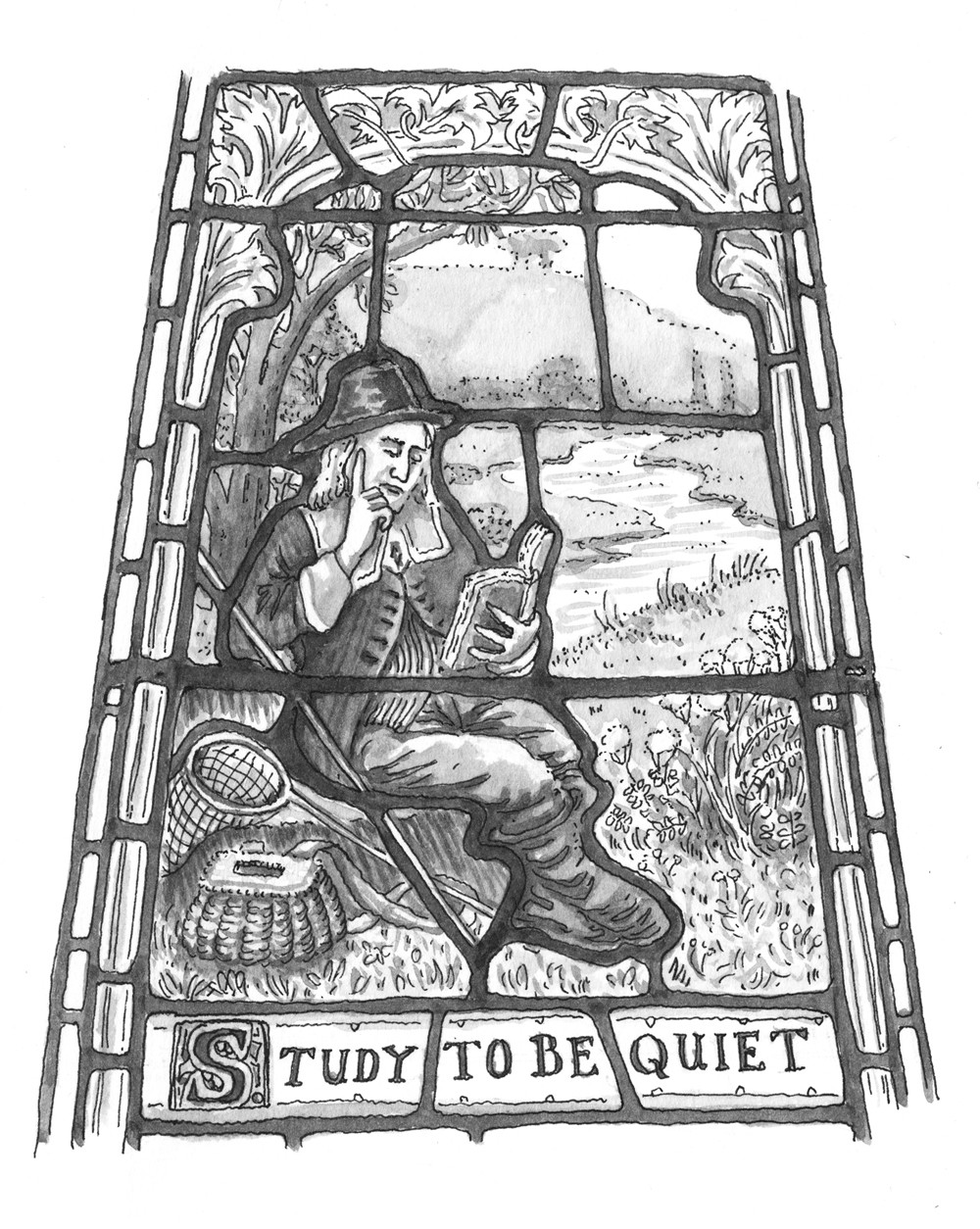

I have the chapel to myself this morning and settle on a rustic pew to admire the manner in which the rising sun sprays harlequinned light across the author’s monument from the window above the altar. The stained glass is relatively new, installed in 1914, and erected in Walton’s memory by admiring fishermen from Britain and America. My eye is drawn to the bottom right-hand corner of the window, where I spy Walton, dressed in a broad-brimmed hat, lace collar and high boots, quietly reading on the bank of the River Itchen with St Catherine’s Hill rising in the background. He sits beneath the shade of a small tree, his rod, net and creel resting by his side. The scene is captioned with his favourite quotation, taken from St Paul’s first epistle to the Thessalonians, ‘Study to be quiet’, which is also the last line of his famous treatise on angling. Walton seems perfectly composed, and I wonder what he is reading. I clear my throat.

‘Any luck?’ I

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI came to Winchester Cathedral to pay homage to one of my favourite authors. Not Jane Austen, though. I enjoy her work, but she doesn’t need my support. When I arrive, a bevy of young admirers is already crouching over her foot-worn monument, striking poses and taking selfies with their smartphones. No, I have come to find the final resting place of Izaak Walton, author of The Compleat Angler.

I am directed to a tiny side chapel in the south transept – called Prior Silkstede’s Chapel – where I find the writer pressed beneath a thick slab of black marble before the altar. Walton died on 15 December 1683, aged 90, and there is a pious, rather conventional poem carved on the stone, ending with the Latin tag: Votis modestis sic flerunt liberi, which I translate as ‘This modest prayer his weeping children lament’, revealing, perhaps, my lack of a classical education. I have the chapel to myself this morning and settle on a rustic pew to admire the manner in which the rising sun sprays harlequinned light across the author’s monument from the window above the altar. The stained glass is relatively new, installed in 1914, and erected in Walton’s memory by admiring fishermen from Britain and America. My eye is drawn to the bottom right-hand corner of the window, where I spy Walton, dressed in a broad-brimmed hat, lace collar and high boots, quietly reading on the bank of the River Itchen with St Catherine’s Hill rising in the background. He sits beneath the shade of a small tree, his rod, net and creel resting by his side. The scene is captioned with his favourite quotation, taken from St Paul’s first epistle to the Thessalonians, ‘Study to be quiet’, which is also the last line of his famous treatise on angling. Walton seems perfectly composed, and I wonder what he is reading. I clear my throat. ‘Any luck?’ I enquire, indicating the creel. He looks up from his book and regards me with a gentle smile. ‘No, not yet. But no day is spoiled that is spent fishing. For if I have not as yet caught a trout, my morning has not been wasted, for have I not had ample time for contemplation?’ ‘I suppose. Might you, um, have any profound thoughts to share?’ ‘I was thinking that the world is full of wonders and how it is man’s lot to know so little of God’s creation. For example, Pliny’, he he points to the book in his hand, ‘is of the opinion that many of the flies with which we tempt the trout have their birth from a kind of dew that falls in the spring. The dew that falls on the leaves of trees breeds one kind of fly, that which falls upon flowers and herbs another, that on cabbages, yet another. In the same way, Gesner, who has written much on fishing, states that the pike, who is the tyrant of these waters, is bred by generation, as other fishes are, but may also spring spontaneously from the pickerel weed with the help of the sun’s heat. Though men of science ponder these mysteries and others like them, I feel that we shall never plumb their bottom.’ I don’t quite know what to say to this, so I change the subject. ‘I saw some very nice trout in the Itchen yesterday. I’m surprised that there aren’t more fishermen about.’ I point to the meandering river winding out of sight beyond the frame of the window. ‘This is private water. It belongs to the Bishop of Winchester, who is an old friend of mine. He is jealous of his privileges, and does not give permission easily.’ ‘Must be nice to be rich.’ ‘Nay, for the rich are always worried for coming of the next day. I would much rather be an angler, for do we not sit on cowslip banks, enjoy the cuckoo’s song, and possess ourselves in as much quietness as this silver stream? I envy no man who eats better meat than I do, or who wears better clothes than I do, only him who catches more fish than I do.’ He laughs. ‘God never did make a more quiet, calm, innocent recreation than angling.’ ‘So I’ve read.’ He raises his eyes to the heavens and snaps his book shut. ‘The noonday sun is passed. You will forgive me, but there are reaches of this river I wish to tempt before the afternoon is spent and I must return to my daughter’s fireside.’ He slips the book into his pocket and gathers up his fishing tackle. ‘Remember, he that hopes to be a good angler must not only bring an inquiring, searching and ob- serving wit, but he must bring a large measure of hope and patience to the art. Adieu.’ And with that he walks out of the frame.*

Izaak Walton lived as an ironmonger in London until the English Civil War, when he closed his shop, took early retirement and moved to a small farm in the country near Shallowford in Staffordshire. There he began the book that would make him famous. The Compleat Angler is a scrapbook containing everything Walton knew about the pursuit of angling. It’s hard to classify, for it contains fishing tips and bait recipes but also songs and poems and a spirited debate between a fisherman, a hunter and a falconer about the merits of each sport. (Of course, the fisherman wins the debate.) The first edition was published in 1653, two years after the Civil War ended, but he never really stopped working on it. New editions would continue to be published until his death. The final edition of 1676 was greatly expanded, and included an additional book written by his good friend Charles Cotton about the art of fishing with a fly for trout or grayling. Walton spent the last forty years of his life writing and fishing in the company of like-minded friends, many of them clergy. He had close ties to the Church of England. His first wife had been the great-great-niece of Archbishop Cranmer, author of the English Book of Common Prayer. Walton’s second wife was the stepsister of the Bishop of Bath and Wells. The poet John Donne was a close friend, for Donne was the vicar of St Dunstan-in-the-West in London when Walton was the verger and churchwarden there. In fact, after Donne’s death, Walton would be asked to write a short biography of the poet, which proved so successful that he followed it up with a series of other pocket-sized biographies, most of them of prominent clergymen. As an old man, Walton would find a home in Farnham Castle as the guest of his friend George Morley, the Bishop of Winchester. Walton’s daughter married the prebendary of Winchester Cathedral, and it was in her home that he would spend his final days. The biggest myth surrounding Walton is the idea that he was a dedicated dry-fly fisherman. In fact, he was ecumenical in his fishing tastes. His book lists many methods of catching fish, including the use of live bait. Of the frog as an excellent bait for pike, he famously (or infamously) remarked, ‘Use him as though you loved him, that is, harm him as little as you may possibly, that he may live the longer.’ My favourite fishing tip is a bait recipe for coarse fish: ‘You may make another choice bait thus: take a handful or two of the best and biggest wheat you can get, boil it in a little milk, like as frumity is boiled; boil it so till it be soft; and then fry it, very leisurely, with honey and a little beaten saffron dissolved in milk . . .’ Sounds delicious. If I were a fish, I’m sure I would find this irresistible. But the book is not just a manual for fishermen. It would hardly have stayed in print all these years if that’s all it was; for The Compleat Angler is the most frequently reprinted book in English after the Bible. Angling, to Walton, represents an approach to life that is at once gentle, pious and reflective. When fishermen are accused of being simple, Walton’s narrator, Piscator, replies:Some readers have detected a hidden code in the book as well, where ‘Angler’ may be read as ‘Anglican’, where the virtues celebrated in fishermen are really the virtues Walton championed in Englishmen of a certain stripe; for at least one cause of the English Civil War was the desire of some sects to break free of the English Church, to abolish bishoprics and replace church hierarchy with a looser Presbyterian-style organization. Walton was an Anglican and a Royalist. He stood for tradition and received wisdom. But he was not a violent man. In fact, there is only one story which survives that portrays him as an active participant in the struggle, and it may be apocryphal. He is said to have once helped smuggle an important royal jewel, called the Lesser George, out of England to Charles II in exile. Otherwise Walton led a retiring life, choosing to sit out the war and the Commonwealth in a quiet country backwater, spending his time writing and fishing. It is this gentle, good-natured man who comes across in the pages of The Compleat Angler, full of friendly advice, not all of it wise, and it is his lyrical celebration of pastoral life, with its cowslip banks and birdsong, its musical milkmaids and quiet country inns with their lavender-scented sheets, that we remember with such fondness.If by that you mean a harmlessness, or that simplicity which was usually found in the primitive Christians, who were, as most Anglers are, quiet men, and followers of peace; men that are simply wise, as not to sell their consciences to buy riches, and with them vexation and a fear to die; if you mean such simple men as lived in those times when there were fewer lawyers . . . then myself and those of my profession will be glad to be so understood.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 54 © Ken Haigh 2017

About the contributor

Ken Haigh is the author of Under the Holy Lake: A Memoir of Eastern Bhutan. He lives on the banks of the Beaver River in Ontario, Canada, where you might find him casting a fly during the trout season.