The generation that survived two world wars seemed to like nothing better than to go on reading about them. Well into the 1950s bookshops in the UK awarded pride of place to covers featuring grown-ups in cap and uniform superimposed on scenes of exploding ordnance and diving aircraft. In non-fiction as in fiction ‘War’ dominated the High Street; part-works, comics, board games and films catered to the same taste. Then around 1958, possibly in reaction to the Suez débâcle, ‘War’ began beating a retreat. ‘History’, ‘Travel’ and ‘Biography’ were encroaching. Within a decade the uniforms and the bombs had been banished to subterranean stacks now entitled ‘Military’.

This was great news for those of us who had been toddlers in home-knits in 1945 and were now, as school-leavers, developing an allergy to Alistair Cooke’s fruity delivery and Alan Taylor’s perorations to camera. We preferred Alan Moorehead. Here was someone who didn’t broadcast and didn’t condescend. He wasn’t even British; and he encapsulated the change in reading tastes. In fact he seemed to orchestrate it, for while other wartime chroniclers were being shunted off to the bookshop basements, he stayed put just inside the door. Moorehead, the famous war correspondent, had reinvented himself as Moorehead, the inspirational historian of travel.

The transformation had not been straightforward. A justly celebrated trilogy on the desert war in North Africa, published in the 1940s when he was on the staff of the Daily Express, had been followed by books on Field Marshal Montgomery, Gallipoli and the Russian Revolution. Of these only Gallipoli won prizes; and a couple of novels were decided failures. But in the late 1950s Moorehead produced a book on the plight of Africa’s wildlife. He had put war behind him, and it was probably while travelling with the kudu and the giraffe that he got the idea for a work on the exploration of the Nile and its c

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe generation that survived two world wars seemed to like nothing better than to go on reading about them. Well into the 1950s bookshops in the UK awarded pride of place to covers featuring grown-ups in cap and uniform superimposed on scenes of exploding ordnance and diving aircraft. In non-fiction as in fiction ‘War’ dominated the High Street; part-works, comics, board games and films catered to the same taste. Then around 1958, possibly in reaction to the Suez débâcle, ‘War’ began beating a retreat. ‘History’, ‘Travel’ and ‘Biography’ were encroaching. Within a decade the uniforms and the bombs had been banished to subterranean stacks now entitled ‘Military’.

This was great news for those of us who had been toddlers in home-knits in 1945 and were now, as school-leavers, developing an allergy to Alistair Cooke’s fruity delivery and Alan Taylor’s perorations to camera. We preferred Alan Moorehead. Here was someone who didn’t broadcast and didn’t condescend. He wasn’t even British; and he encapsulated the change in reading tastes. In fact he seemed to orchestrate it, for while other wartime chroniclers were being shunted off to the bookshop basements, he stayed put just inside the door. Moorehead, the famous war correspondent, had reinvented himself as Moorehead, the inspirational historian of travel. The transformation had not been straightforward. A justly celebrated trilogy on the desert war in North Africa, published in the 1940s when he was on the staff of the Daily Express, had been followed by books on Field Marshal Montgomery, Gallipoli and the Russian Revolution. Of these only Gallipoli won prizes; and a couple of novels were decided failures. But in the late 1950s Moorehead produced a book on the plight of Africa’s wildlife. He had put war behind him, and it was probably while travelling with the kudu and the giraffe that he got the idea for a work on the exploration of the Nile and its colonial aftermath. This came out as two books, The White Nile in 1960 and The Blue Nile in 1962. Both were sensational successes and have been through innumerable editions. Academic unease did not diminish their appeal, nor did his free use of iffy adjectives (‘primitive’, ‘barbaric’, ‘depraved’, ‘Stone-Age’) tarnish their lasting worth. Only of late, with supermarkets acting as the arbiters of what the nation shall read, has some myopic publisher allowed them to go out of print. One can savour the Nile books purely for the joy of Moorehead’s companionable prose and deft characterization. But he was also a consummate artist. An eye for the inconsequential detail had characterized his journalism and now illumined the Dark Continent’s history. When in The White Nile the explorer John Hanning Speke attempts to circumambulate Lake Victoria, he ventures into the unvisited kingdom of Buganda. Ruled by a young and intelligent psychopath, this is a dangerous place. ‘Hardly a day went by’, writes Moorehead,without some victim being executed at [King Mutesa’s] command, and this was done wilfully, casually, almost as a kind of game . . . Mutesa crushed out life in the same way as a child will step on an insect, never for an instant thinking of the consequences or experiencing a moment’s pity . . . The Queen-Mother . . . kept her separate court at a little distance from Mutesa’s palace. She was not often sober. Drinking, smoking and dancing to the music of her personal band were the usual occupations of the Queen-Mother’s hut, and it was not surprising that she complained . . . [of ] bad dreams and illness of the stomach. Speke dosed her from his medicine chest and advised her to give up drinking. But she was not a good patient. Returning to her hut one day Speke found himself involved in an orgy which ended in the Queen-Mother and her attendants drinking like swine on all fours from a trough of beer.

Such narrative seems to emerge effortlessly from turgid eighteenth- and nineteenth-century accounts that were often little more than journals.‘I haven’t got anything marvellous to tell. I wish I had,’ wrote Mansfield Parkyns in the preface to his Life in Abyssinia. Moorehead admired the man’s modesty but begged to differ. Reading voraciously, he could conjure drama out of a gazetteer.

His own experience constituted an equally valid kind of research and was used to delicious effect in descriptions of the desert, sahel, forest and jungle, and of the wildlife and anthropology. Scholarship and adventure were for Moorehead not just compatible but complementary; travel lent colour to the history-writing, history lent respectability to the travel-writing. For anyone accustomed to thinking history was all about documents and travel all about egos, it was a revelation. Rich pickings beckoned, and in two further books on exploration Moorehead himself worked this seam to brilliant effect. Then in 1966 his output ceased. A couple of earlier works were exhumed and published, yet he wrote no more. He was 56. By what, for a compulsive writer at the height of his powers, was a cruelly specific fate, he would live and occasionally travel for another seventeen years without being able to craft a sentence. Unbeknown to his public, that ‘deep silence of the bush’ evoked in the Nile books had descended on their author.

*

An odd thing about big rivers is that they nearly all traverse the map horizontally. They flow west-east or sometimes east-west. Only the Nile has an unmistakably north-south axis. With its delta in Egypt lying almost exactly due north of its source in Uganda, it strays no more than a degree or two from the meridian throughout its 4,000-mile course. Moorehead didn’t investigate this phenomenon, though it might explain the river’s fascination to the ancients. Herodotus had explored up to Aswan, and Ptolemy had adopted a theory that the White Nile flowed from two great lakes far to the south. If not much else, they knew it came from the equator and pointed to the pole. Like the regularity in the revolutions of the planets, this suggested purpose. The idea that the distribution of distant landmasses and seas might also exhibit some symmetry resulted.

For Moorehead, whose wartime base had been an apartment in Cairo’s midstream Gezira district, the river’s sense of purpose lay in another curiosity: its copious waters issued from a desert, and they had been doing so with a timeless consistency that was responsible for the oldest cradle of civilization on the planet. Moorehead, born and raised in Melbourne, was as intrigued by the hydrography as by the antiquity. In late 1940 he visited Khartoum and saw the confluence of the river’s two greatest feeders, the White Nile from Equatoria and the Blue Nile from Ethiopia. How they reached this point and who had first unravelled their farther geography was not common knowledge. Perhaps he already sensed a story.

‘Escaping’, as he put it, from suburban Australia, he had reached Cairo after making a name for himself as a correspondent in Paris. Short and bumptious, he combined Bogart looks with a blubbery grin and lots of cheek; plum assignments, like attractive women, came his way easily. The war turned him into a star correspondent and the three books based on his desert dispatches turned him into an esteemed author. By the late 1950s, when he resumed his interest in the river, he was a celebrity, married with a family and often resident in Italy where the Mooreheads hobnobbed with Hemingway, Freya Stark and Bernard Berenson.

It would be interesting to know whether he discussed his new project with any of these luminaries. Arranging the Nile’s story posed formidable problems. Its conquest had probably attracted more colourful characters, provoked more bitter controversy and triggered more colonial carnage than any other river; it opened Africa up and inaugurated the international ‘scramble’ for it – but all this in no very consistent fashion. The time-spread was over a century, the area larger than Europe, and although the river’s two feeders suggested two books, it was no easy matter to disentangle their stories.

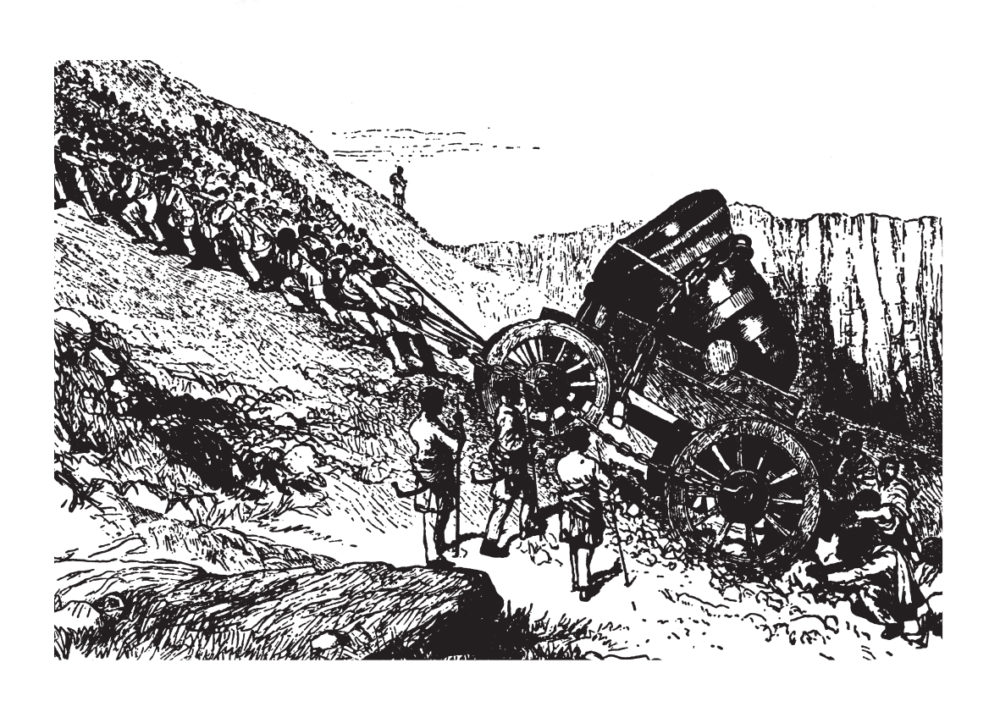

Both volumes were designed to progress from the haphazard feats of the earliest European explorers to the march of armies and the clash of civilizations. In the case of the White Nile, much the longer of the two rivers, this meant scene-setting in East Africa for the mid-nineteenth century exploits of Burton, Speke, Livingstone, Stanley and Baker, and then skipping upriver to Sudan to catch Gordon’s last stand and Kitchener’s end-of century nemesis. The Blue Nile, on the other hand, is shorter (as is the book) and more impetuous; its source is far higher than Lake Victoria, and its Ethiopian catchment provides the seasonal deluge on which all life in Egypt depends. This logic seems to have persuaded Moorehead that his The Blue Nile should include Egypt, although the Blue Nile itself goes nowhere near it. As with The White Nile it also meant skipping about – from Ethiopia for James Bruce’s 1770s travels, to Egypt for the Napoleonic conquest, then Nubia for Johan Burckhardt’s story, and so back to Ethiopia for Lord Napier’s assault on the luckless emperor Theodore. This last happened in 1868. Somewhat confusingly, Moorehead’s sequel was more a prequel. All of which might have made for structural confusion; indeed Clive James, while perhaps overpraising Moorehead as ‘Australia’s first really conspicuous gift to English international prose’, disparages the Nile books as ‘shapeless’ and ‘indeterminate’. Arbitrary they may be but, for me, not shapeless. For in the arrangement lies the art. By manipulating an otherwise unwieldy history, Moorehead discovered that direction and purpose which make the Nile books such compulsive reading. The same skill would fashion a classic of Australian exploration in Cooper’s Creek (1963) and of Pacific exploration in The Fatal Impact (1966). The title of the last now seems prophetic. Later that year, 1966, Moorehead experienced severe headaches. A diminished blood supply to the brain was suspected, and during hospital tests he suffered a major stroke. The physical paralysis that resulted would be partly reversed, though not the brain damage. He would never pen another line, read another word, or utter more than a couple of stock interjections. ‘Absolutely’ was one of them. In other respects ‘absolute was the silence’, like that which hung over Lake Tana at the source of the Blue Nile. It was as if the river had claimed one of its own.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 26 © John Keay 2010

About the contributor

Publishers willing, John Keay is pulling out of China to return to India, possibly by way of Tibet. Otherwise he still lives in Scotland.