The eternally, infernally straight roads of the deserts of northern Mexico cut through some of the flattest, most barren country you’ll ever see. On my travels I’ve been through this land. You get on a bus in a station in a city filled with life’s cacophony and drive for days, with the heat suffocating you asleep and the mosquitoes stinging you awake, and the only change from bush and scrub is the odd vulture eyeing you suspiciously. Then, just when you think you’ve landed in the bleakest place on earth, without a human or a sign of one for miles, the black-clad lady who has been sitting quietly beside you for the past twelve hours taps the driver to stop, unloads her overflowing bags and cases, and wanders off into the scrub . . .

It was in this environment that Insurgent Mexico was written. Published in 1914, it is ostensibly the reportage of the months that the journalist John Reed spent with Pancho Villa’s revolutionary guerrillas as they advanced through the desert to Mexico’s capital. But it is more travelogue than journalism, more loving portrait of a people and a country than war reporting. Reed’s reports have the passion and eye for detail of Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London and are painted with the eye of a poet who was never far from the action – all the more remarkable given the punishing terrain.

John Reed is best known for Ten Days that Shook the World (1917), his classic account of the Bolshevik revolution. But where Ten Days rata-tat-tats like a telegram tapped out under gunfire, Insurgent Mexico slaps across a literary canvas lavish swathes of colour and furious heat and open-hearted characters and swirls them around till you can taste the dust, feel the sweat dribbling down your back and find yourself casting round for your horse, your woman an

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe eternally, infernally straight roads of the deserts of northern Mexico cut through some of the flattest, most barren country you’ll ever see. On my travels I’ve been through this land. You get on a bus in a station in a city filled with life’s cacophony and drive for days, with the heat suffocating you asleep and the mosquitoes stinging you awake, and the only change from bush and scrub is the odd vulture eyeing you suspiciously. Then, just when you think you’ve landed in the bleakest place on earth, without a human or a sign of one for miles, the black-clad lady who has been sitting quietly beside you for the past twelve hours taps the driver to stop, unloads her overflowing bags and cases, and wanders off into the scrub . . .

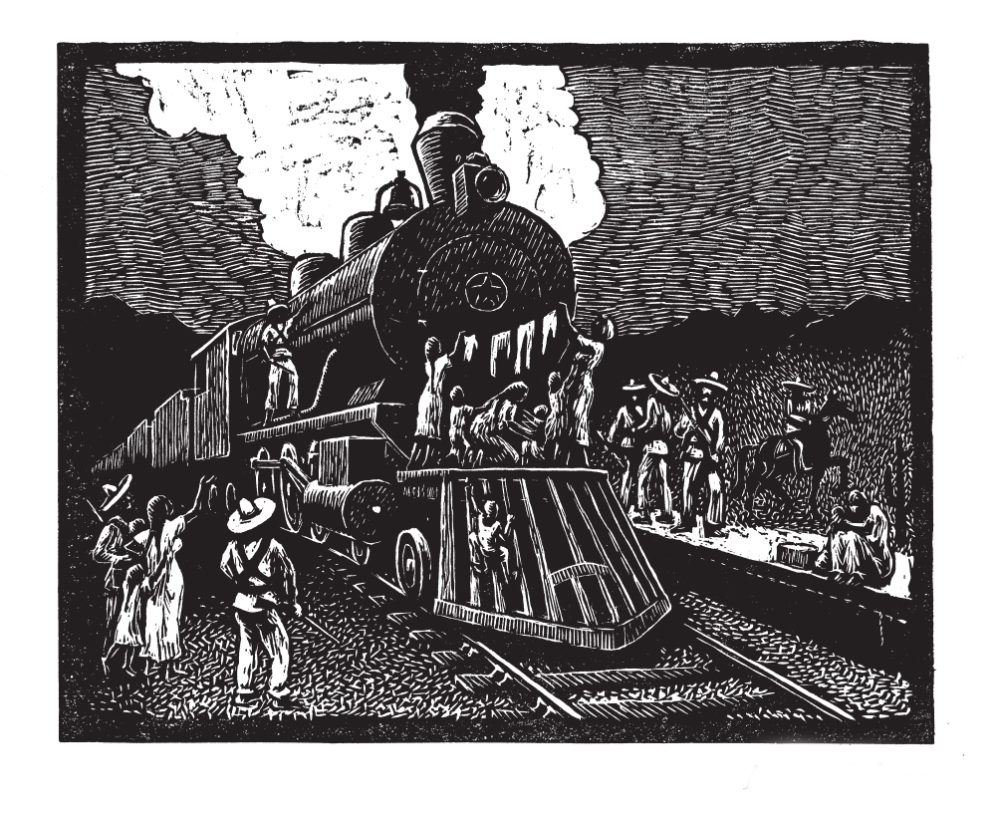

It was in this environment that Insurgent Mexico was written. Published in 1914, it is ostensibly the reportage of the months that the journalist John Reed spent with Pancho Villa’s revolutionary guerrillas as they advanced through the desert to Mexico’s capital. But it is more travelogue than journalism, more loving portrait of a people and a country than war reporting. Reed’s reports have the passion and eye for detail of Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London and are painted with the eye of a poet who was never far from the action – all the more remarkable given the punishing terrain. John Reed is best known for Ten Days that Shook the World (1917), his classic account of the Bolshevik revolution. But where Ten Days rata-tat-tats like a telegram tapped out under gunfire, Insurgent Mexico slaps across a literary canvas lavish swathes of colour and furious heat and open-hearted characters and swirls them around till you can taste the dust, feel the sweat dribbling down your back and find yourself casting round for your horse, your woman and your gun. Reed grew up in Portland, Oregon, studied literature at Harvard, where he was snubbed by the smart set, fell in with a bohemian crowd in New York in his twenties and, in 1913, was sent to report on the Mexican revolution by his magazine. While bigger journalistic names than he, scared of the government soldiers’ edict against reporters, filed fictitious copy from the bars of Texan border towns, Reed, hungry for adventure and eager to make a name for himself, paid a trader to take him deep into Mexico, to the front. He pitched up at the house of one of Villa’s generals and through charm (and, no doubt, hard cash) inveigled his way into becoming embedded (decades before the term was invented) with La Tropa, a rag-tag band of Villa’s anti-government troops. What a sight this well-to-do Harvard boy with bug eyes, a rower’s physique and snappy suits must have been to the young illiterate natives turned soldiers – they in their tight cowboy trousers and brightly coloured serapes (long shawls, similar to a poncho), and most of them barefoot. But they quickly took to him once he downed a bottle of sotol (a distilled spirit, similar to mezcal and tequila). By night the young journalist and even younger revolutionaries drank and danced under the moonlight and talked of their girls and ‘what we will do when we really get at it’, and by day they chased coyotes, roped steers and rode at speed through the desert in punishing heat with equally ferocious hangovers. Here is where we are grateful that Reed’s reporting was partisan, as he lovingly describes what he saw:But at dawn one day, the camaraderie turned to tragic farce. The Tropa were charged with defending a mountain pass against the notorious irregulars, the colorados, but their advance guard fell asleep. As a thousand colorados galloped towards them through the desert, the camp, with just a hundred fighting men, became a frenzy of soldiers, women, children and animals rushing about in panic. Reed described how on the horizon, lines of dust steadily advanced and then became clear black figures, hundreds of them, as far as the eye could see. He ran as hard as he could away from the death that was fast approaching, dumping his coat, camera and notebooks and veering off the road into the chaparral. There he tripped on a root and rolled down an incline into a ditch. As he lay panting, two colorados on horseback not ten feet away let out a bloodcurdling scream and he waited for death . . . but they galloped straight past him. Exhausted from the explosion of tension, Reed promptly fell asleep. Waking up not long after in the burning morning sun, he walked for ten hours through the scrub. He was taken in at a ranch by a blacksmith who insisted he slept in his bed, an example of Mexican hospitality which holds that ‘a stranger might be God’. There he bathed in natural hot springs beside a priest, also on the run. Then came the sickening news: two of his closest Tropa friends were dead, cut down fighting to their last bullet. And here his underlying theme of the futility of war intrudes: ‘so many useless deaths in a petty fight’. His desire for experience and material cut both ways. Scarred but undeterred, he again wangled his way into the heart of the fighting, winning a scoop with Pancho Villa himself, and passage with his troops on the army train as they bore down on the federal stronghold of Gómez Palacio. In a superlative thirty-page sketch Reed countered the prevailing image of Villa as an illiterate cattle rustler, instead showing him as a charismatic leader and a brilliant war tactician who, ‘where the fighting was fiercest . . . [was] among them, like any common soldier’ and was ‘without . . . any doubt, the greatest leader Mexico has ever had’. Reed then painted a picture of a battered but resilient army on the move. On the cowcatcher of the train he saw two women and five children set up camp, baking tortillas while ‘over their heads, against the windy roar of a boiler, fluttered a little line of wash’. He watched a boy, lugging a rifle and clearly ravenous, pounce on a piece of rotting, stale tortilla on the ground, then, realizing Reed was watching, throw it to the ground with contempt, snarling, ‘As if I was dying with hunger.’ On the platform before they moved off ‘peons with big straw sombreros and beautifully faded serapes, Indians in blue working clothes and cowhide sandals, and squat-faced women with black shawls around their heads, and squalling babies packed the seats and platforms, singing, eating, spitting, chattering.’ The army train arrived at its target, a town on a hill called Cerro de la Pila. Reed watched as Villa led the assault of machine-guns and blasting artillery, his men climbing in line up the black hill into the federal troops’ fire. Seven times they attacked and seven times they were repulsed, and each time seven-eighths of them were killed. The next day Reed found that the hill was still in enemy hands and all the slaughter had been for nothing. The town did eventually fall, but the vision of that initial slaughter stayed with Reed: ‘It was an incredible dream, through which the grotesque procession of wounded filtered like ghosts in the dust.’ Reed maintains the vivid imagery right to the end in three scenes of Mexican life as he relates his adventures in a casino, at a dance and at a play. In a vignette of a small mountain town called Valle Alegre (Happy Valley) he takes a wide-angle view – the village ‘flooded in strong moonlight’, the jumbled roofs silvery in the distance; then he focuses in – ‘life sounds quicken’, he hears the excited laughter of girls; a man talking to a woman through the bars of her window makes her catch her breath; a dozen guitars syncopate each other; a hot smoky alcoholic breath smites him. The mood is romantic, excited, and we can see the stars, smell the hops and recoil like the woman as we cringe at the man’s patter . . . The reports made Reed a star. In them he pioneered (along with Stephen Crane, Lincoln Steffens and others) a new style of journalism that used literary techniques and blended fact and fiction over half a century before it was made famous by the likes of Truman Capote, Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe. Insurgent Mexico can feel a little disjointed, perhaps because it is made up of reports filed from the front, only loosely collected and lightly edited. But then war is messy, illogical and unstructured. And when a people is fighting for its life and a nation for its soul, perhaps only a poet such as Reed can do justice to the struggle.The sun hung for a moment on the crest of the red porphyry mountains, and dropped behind them; the turquoise cup of sky held an orange powder of clouds. Then all the rolling leagues of desert glowed and came near in the soft light . . . a great silence, and a great peace beyond anything I have ever felt, wrapped me around. It is impossible to get objective about the desert; you sink into it, become part of it.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 30 © Hugh Farmar 2011

About the contributor

Hugh Farmar lives in London. He visited Mexico for two days in 2007 and ended up living there. He doesn’t rule out its happening again.