I have read so much Updike, so many articles, so many collections of his criticism and journalism, and virtually all his many novels, that I sometimes think I know more about his thought processes than I do about my own.

In his introduction to The Early Stories, 1953–1975, John Updike speaks candidly about his professional life. His inspiration, he says, has been drawn from life; he has always believed that ‘out there was where I belonged, immersed in the ordinary which careful explication would reveal to be the extraordinary’. And this, I think, gave him the leitmotif of his writing life and made him the writer he became.

He was, consciously, the product of small-town Pennsylvania and always his remarkable mother’s son. His father, a schoolteacher, is a rather shadowy figure in his accounts. His mother moved the family from their home town of Shillington out to a farm in the countryside, which Updike described as ‘the crucial detachment of my life’. In the late Forties and Fifties he had discovered the joy of films, and he would go to local movie houses as often as possible, experiences which he treasured and described nostalgically. He once wrote a wonderful line: all movies are really the story of two huge faces on a screen coming together and eventually kissing.

For the rest of his life he harked back to Pennsylvania, most obviously for his Rabbit Angstrom novels; he cherished the local idiom, the banality of conversation, the deep-grained, unthinking patriotism, the rumours of adultery, and all the small endeavours and lapses of the people in the towns he knew. He had a great visual awareness too, and many of the towns he appropriated are almost lovingly summoned, even as they are lapsing into neglect and decay.

In his progress from rural Pennsylvania, via Harvard and Oxford, to international celebrity, he never tried to distance himself from his background. In fact he needed it as a kind of emotional base camp, something that he could explore and use. During his year in Oxford he studied drawing at the Ruskin. He had a very intense, almost painterly, appreciation of place, a sensitivity he applied to writing his novels, so that his descriptions of New York, New England and Pennsylvania are rich and precise. He was a wonderful observer of art; over the years he wrote some outstanding art criticism for the New York Review of Books and other magazines. His last piece about art appeared in the New York Times shortly before he died in 2009. Poignantly it was called ‘Always Looking’. The year before he had reviewed the J. M. W. Turner exhibition in Washington with his customary diligence and insight.

He was always an original boy, in his early days obsessed with paper and cartoons rather than the act of writing. He sent off stories and cartoons and they began to be published. He was very young, with a growing family, when he was invited to join the staff of the New Yorker i

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI have read so much Updike, so many articles, so many collections of his criticism and journalism, and virtually all his many novels, that I sometimes think I know more about his thought processes than I do about my own.

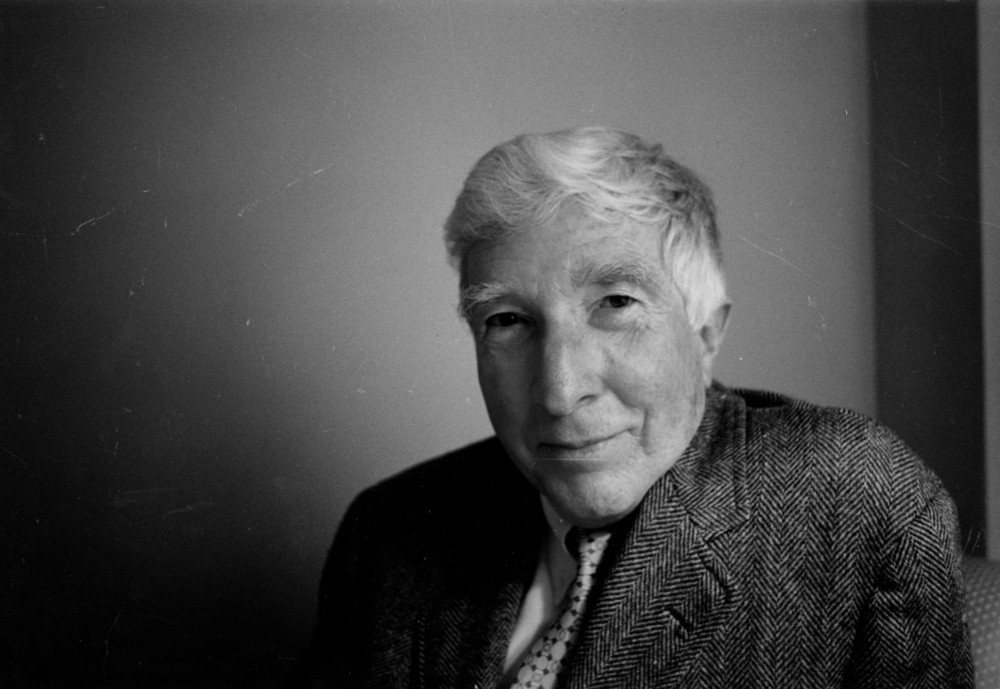

In his introduction to The Early Stories, 1953–1975, John Updike speaks candidly about his professional life. His inspiration, he says, has been drawn from life; he has always believed that ‘out there was where I belonged, immersed in the ordinary which careful explication would reveal to be the extraordinary’. And this, I think, gave him the leitmotif of his writing life and made him the writer he became. He was, consciously, the product of small-town Pennsylvania and always his remarkable mother’s son. His father, a schoolteacher, is a rather shadowy figure in his accounts. His mother moved the family from their home town of Shillington out to a farm in the countryside, which Updike described as ‘the crucial detachment of my life’. In the late Forties and Fifties he had discovered the joy of films, and he would go to local movie houses as often as possible, experiences which he treasured and described nostalgically. He once wrote a wonderful line: all movies are really the story of two huge faces on a screen coming together and eventually kissing. For the rest of his life he harked back to Pennsylvania, most obviously for his Rabbit Angstrom novels; he cherished the local idiom, the banality of conversation, the deep-grained, unthinking patriotism, the rumours of adultery, and all the small endeavours and lapses of the people in the towns he knew. He had a great visual awareness too, and many of the towns he appropriated are almost lovingly summoned, even as they are lapsing into neglect and decay. In his progress from rural Pennsylvania, via Harvard and Oxford, to international celebrity, he never tried to distance himself from his background. In fact he needed it as a kind of emotional base camp, something that he could explore and use. During his year in Oxford he studied drawing at the Ruskin. He had a very intense, almost painterly, appreciation of place, a sensitivity he applied to writing his novels, so that his descriptions of New York, New England and Pennsylvania are rich and precise. He was a wonderful observer of art; over the years he wrote some outstanding art criticism for the New York Review of Books and other magazines. His last piece about art appeared in the New York Times shortly before he died in 2009. Poignantly it was called ‘Always Looking’. The year before he had reviewed the J. M. W. Turner exhibition in Washington with his customary diligence and insight. He was always an original boy, in his early days obsessed with paper and cartoons rather than the act of writing. He sent off stories and cartoons and they began to be published. He was very young, with a growing family, when he was invited to join the staff of the New Yorker in 1954; after two years he retreated from New York to an ordinary town in Massachusetts and he stayed in the area until he died. He was a Yankee, in some ways, in his decency and deliberateness, I thought, despite his background. All his life he loved Harvard and what he had achieved there on the staff of the Harvard Crimson, a traditional starting-point for budding Harvard writers. I have more or less worshipped Updike since I first read his short story ‘Pigeon Feathers’, long before I came from South Africa to England and Oxford. Some years ago I went to Boston to interview him and we spent what he described as ‘a beguiling three hours’. It is there, in one of his books I asked him to sign. I am not sure I beguiled him, but he certainly beguiled me. He had deeply ingrained good manners, old-fashioned manners. When we met at a very grand hotel in Boston, he was concerned that I was not wearing a tie; he thought it was obligatory, but I had checked and I told him so. He smiled wanly; it was a small insight, I thought, into both his parochialism and the extent of his Yankee sensibility. In my study, I keep a photograph of him that I took at our first meeting, and his gentle, knowing smile is warming. He had a large nose, which gave him the appearance of the prow of a boat. When we talked he seemed surprised that I knew his books so well, and particularly surprised that I had read The Coup (1978). This little-known book is set in tropical Africa – Updike had half-African grandchildren – and it is an astonishing piece of work. He told me that day that the only excuse for reading is to steal, so I felt able to tell him that my first serious novel, Interior, owed a lot to The Coup. What is particularly astonishing about The Coup is that it is not about a world Updike knew well, yet it has a beautiful and imaginative lyricism and an unforgettable inventiveness which give the lie to the theory that he could only write what he saw. The Coup suggests to me that, had he wanted to, he could have had another, quite different career. And perhaps it would have been different if he had not struck a rich vein with the Tarbox novels, set on the beaches and in the houses of the young and adulterous of Massachusetts. One novel alone, Couples, published in 1968, earned him more than $1 million, a huge amount back then. It was almost scandalously explicit, and of course avidly read. I once asked him about the difficulties of writing about sex and he said that as a writer you have to apply the same standards to all sections of a novel: you can’t restrict yourself by cutting away to agitated palm trees or suggestive waves crashing on a beach. He was, in his own way, religious; in his short story ‘The Deacon’ you get the strong sense that for Updike – as for the deacon himself – faith is the persistence and continuity of humanity, possibly inseparable. His faith was also a kind of pantheism: God could be found in the architecture of churches and in the persistence of habit. In ‘The Deacon’ his description of Miles, who opens the church door to find that there are no worshippers, is very moving: ‘Miles is not displeased. He is pleased. He has done his part. He has kept the faith. He turns off the lights. He locks the door.’ The tug of the spiritual, the demands of marriage, the temptations of the material world and the preoccupation of the unique self, all pulling in different directions, is a familiar Updikean tension. Updike spent his life grappling intelligently with questions about faith and the afterlife. His position was simply that there can’t be total extinction. Updike was a diligent writer. He liked to get up after the domestic work was done, and he would work with intense concentration virtually every single day. I asked him what he thought about journalism, and he said he liked to see his name in print. His collections of his other work, starting with Hugging the Shore (1983), run routinely to 900 pages. One of his sons wrote that he applied a certain steeliness and single-mindedness to his writing, seldom compromising for the sake of the family. Updike loved women. Not long before he died he wrote a very warm memoir of his first wife, which seemed to me to be a sort of apology for his earlier behaviour. In my experience, serial adulterers, if they are also writers, feel faintly queasy as they grow older, both because of what they have done and what they have appropriated for their own ends. My contact with Updike led to my being asked by him to write the foreword for a reissue of Rabbit at Rest (1990). I was, and still am, very proud to have my name in his book. His only comment was to say that his father was not a schoolmaster – as I had described him – but a teacher. He seemed to think that a schoolmaster was an administrator. I did not dare correct him. Rabbit at Rest, I think, is the finest novel to come out of the last quarter of twentieth-century America. You will find lots of people who would disagree. There is something about his (mostly) realistic style, his gentlemanly demeanour, his attention to minor issues, as understood by his characters, and his lifelong project to depict his country in all its wisdom and foolishness, in its essential innocence and its longings, which has led some critics to underestimate him as rather mundane. It is true that his work was often about the quotidian, but it was written with wonderful deftness and originality. I think it was this perceived lack of interest in big issues that prevented him from being awarded the Nobel Prize. How many people really believe that Nadine Gordimer or Vargas Llosa or Doris Lessing are better writers than Updike? The most difficult task for a writer is to make real and interesting an apparently unexceptional character. With Rabbit at Rest, Updike’s dazzling achievement is to write about a man with little education, although Harry Angstrom now describes himself as a history buff; he is delving into his country’s past in his retirement. Life, as Janice his long-suffering wife observes, has more or less been downhill all the way since he was a basketball star in high school. But Harry, who is weak, greedy and disloyal, is somehow true to a vision of himself and of a turbulent America. It is startlingly plausible. New York and New England don’t impinge on Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom’s life or consciousness at all. Rabbit is a man of Pennsylvania, and in a wider way an American archetype. Updike told me that he had never intended to write an extensive series of novels about Angstrom, each one separated by ten years almost by chance, but he had started the first novel because he was finding (if I remember correctly) a proposed book on the inept fifteenth president, James Buchanan, ‘heavy going’. Rabbit, Run was published in 1960. In the subsequent novels Updike seized the opportunity to produce a sort of saga of the Angstrom family, led by Rabbit. By the arrival of Rabbit at Rest, Rabbit has grown fat and his health is not good. Here Updike’s writing reaches extraordinary heights. Of course Rabbit still sees himself as tall and athletic, despite his appalling diet, which includes, inadvertently, some birdseed. Updike’s sympathy for his character seems to me to have grown over the years. His greatest skill to my mind was his ability to create characters out of the unremarked American middle class – a term which has a wholly different resonance from our own middle class – characters who live, even sing, out of their very ordinariness. Updike wrote that Rabbit is like the Underground Man, incorrigible; ‘from first to last he bridles at good advice, taking direction only from his personal, also incorrigible, God’. What I see here is that behind the apparently effortless creation of the common man, Updike has in mind a universal character, and I don’t think that it is at all fanciful to say that he was in his own way the American Dostoevsky, although I think he would have preferred to be compared to Nathaniel Hawthorne.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 47 © Justin Cartwight 2015

About the contributor

Justin Cartwright won many awards for his writing but doubted he’d ever be as famous as John Updike.