With its fashionable but unexplanatory one-word title, Tank is an easy book to overlook or misunderstand when you first come across it. Yet its jacket gives two clues as to why it is so absorbing, astonishing and enlightening.

The first is the name of its author, the cultural historian Patrick Wright, whose earlier books include On Living in an Old Country, A Journey through Ruins and The Village that Died for England – deeply satisfying studies of what appear to be recondite or small-scale subjects but which turn out to be profound excursions into the condition of England. The other is, in fact, its title: not The Tank, but Tank, which signals that this is no straightforward history but, in the author’s own words, an appreciation ‘that the poetics of the twentieth century extend far beyond the literary page’ – extend indeed to the progress of this spellbinding piece of military hardware.

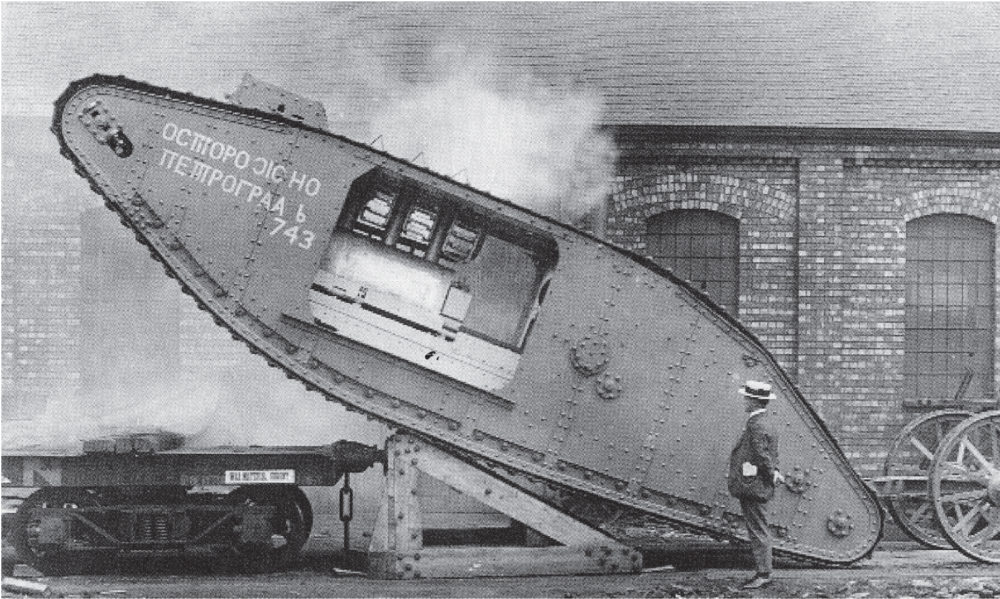

The tank is an emblem of state power, a behemoth that has transformed wars and threatened – and sometimes mown down – civilians. But it has also been seen as a ‘cubist slug’, has inspired a modernist song and dance routine Tanko, has led military men to philosophize, and installation artists to appropriate the rhomboid shape to suggest the ultimate in urban alienation. In short, the tank, as Tank so skilfully and wittily and sadly shows us, stands at the very heart of the twentieth century and points up its follies, its wickedness, its aspirations, its delusions – and occasionally its humanity.

Although the tank had its origins in a ‘modern steam chariot’ – an invention of two Cornishmen in 1838 that would, as they put it, prove ‘very destructive in case of war’– or even perhaps in Boudicca’s chariot, in medieval suits of armour that were ‘living tanks’ or in Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches, its moment was not to come until the First World War. Then

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWith its fashionable but unexplanatory one-word title, Tank is an easy book to overlook or misunderstand when you first come across it. Yet its jacket gives two clues as to why it is so absorbing, astonishing and enlightening.

The first is the name of its author, the cultural historian Patrick Wright, whose earlier books include On Living in an Old Country, A Journey through Ruins and The Village that Died for England – deeply satisfying studies of what appear to be recondite or small-scale subjects but which turn out to be profound excursions into the condition of England. The other is, in fact, its title: not The Tank, but Tank, which signals that this is no straightforward history but, in the author’s own words, an appreciation ‘that the poetics of the twentieth century extend far beyond the literary page’ – extend indeed to the progress of this spellbinding piece of military hardware. The tank is an emblem of state power, a behemoth that has transformed wars and threatened – and sometimes mown down – civilians. But it has also been seen as a ‘cubist slug’, has inspired a modernist song and dance routine Tanko, has led military men to philosophize, and installation artists to appropriate the rhomboid shape to suggest the ultimate in urban alienation. In short, the tank, as Tank so skilfully and wittily and sadly shows us, stands at the very heart of the twentieth century and points up its follies, its wickedness, its aspirations, its delusions – and occasionally its humanity. Although the tank had its origins in a ‘modern steam chariot’ – an invention of two Cornishmen in 1838 that would, as they put it, prove ‘very destructive in case of war’– or even perhaps in Boudicca’s chariot, in medieval suits of armour that were ‘living tanks’ or in Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches, its moment was not to come until the First World War. Then the fortuitous arrival of three constituents – bullet-proof armour, the internal combustion engine and caterpillar tracks – enabled H. G. Wells’s prophecy of ‘Land Ironclads’ to become reality. A lozenge-shaped machine of war, an ‘armed caterpillar which could go through anything and knock down trees’, would, it was hoped, bring to an end the slaughter on the Western Front. It was there, in 1916, that the emblematic nature of the tank first became apparent. ‘Gad,’ wrote a battery sergeant-major of the ‘Land Crabs’, ‘it struck me how symbolic of war they were, creeping along at about four miles an hour, taking all obstacles as they came, spluttering death with their guns, enfilading each trench as they came to it – and crushing beneath them our own dead and dying as they passed. Nothing stops these cars, trees bend and break, boulders are pressed into the earth.’ Others spoke of tanks as ‘low squatting things moving slowly in the mist’ before heading back to their ‘lair’, while the restraints of censorship meant that war correspondents were obliged to compare these new armoured machines to ‘giant toads, mammoths and prehistoric animals of all kinds’. Indeed, as Wright says, the tank triumphed as an exuberant metaphor long before it had been proved as a military machine. The metaphor was continually reworked. In 1919 in the church of St Mary in Swaffham Prior, a small Cambridgeshire village, a stained-glass window was installed. Above the statutory biblical quotation, from the Second Book of Samuel – ‘But the man that shall touch them must be ringed with iron’ – was depicted a tank spraying fire over helpless British soldiers in an adjacent window. Two hundred and sixty-five First World War tanks that had been brought home more or less intact from France and Flanders served as giant piggy banks, sited in town and village squares to extend the idea of War Bonds and Certificates into peacetime thrift. But in Glasgow, the ‘Haig’ and the ‘Beatty’ – tanks that had raised over a million pounds – were joined in early 1919 by a ‘tankodrome’ in the city’s Cattle Market, ready, if necessary, to quell the striking ‘Red Clydesiders’. Even so, in the period between the two World Wars, the tank’s military advocates were few. ‘Fighting the Germans is a joke compared to fighting the British,’ one officer said in exasperation at an Army High Command that could not see the potential of mobile armoured weaponry, that persisted in treating the tank as if it were a Martello tower. One who could was Colonel J. F. C. ‘Boney’ Fuller, a Tank Corps veteran, whose interests lay in Eastern religion ‘about which he could be bewildering’, spiritualism, occultism, Shakespeare ‘whom he admired and understood from an angle of his own’, military history and the theory of war. His fascination with the occult drew him to the notorious Aleister Crowley; his belief that ‘new ideas originate in piratical exploits outside the existing military organization’ to Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists. When war came in 1939, Fuller, excluded from any position in the Army, could only fulminate that while Britain’s enemies had latched on to the potential of mechanized warfare, his own country’s top brass was more concerned with rushing an additional two million men into the nation’s army – ‘human tank fodder’, exploded Fuller – than with concentrating resources on what would win the war: ‘tanks on the ground and aircraft in the air’. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, tanks had been forbidden to Germany, and at first German ‘tanks’ were but ‘tactical representations’ made of wood and painted canvas mounted on cars or tricycles. Hitler, however, was an aficionado of Fuller’s theories, and in April 1939 he invited him to Germany, where he stood next to the Fuhrer at his fiftieth birthday celebration and ‘for some three hours watched a formidable mass of moving metal’. ‘I hope you were pleased with your children?’ Hitler asked. ‘Your Excellency, they have grown up so fast that I now no longer recognize them,’ replied Fuller. It was these ‘unrecognizable children’ that swept through Poland four months later, a country with three and a half million horses and not a single factory producing cars. The brave but hopeless charge made by the Polish lancers against these great iron invaders became legendary. It was the same (or related) armour-plated ‘children’ that swept through the Netherlands, Belgium and France less than a year later, then Greece, Yugoslavia and the Western desert. It was tanks, too, that spearheaded the German invasion of Russia. When the war was over – although in the twentieth century war was never over for long – some distant relative, a more honed and efficient reconciliation of the eternal contradictions of firepower, mobility and protection, permitted the small nation of Israel to ‘win’ in wars against her Arab neighbours. Some Israeli soldiers came to regard their tanks as home: ‘You can be in a tank for days. You build them like a second home: pictures, a place to put your little packet of cigarettes, places to put your special tools.’ In the Cold War and beyond, the tank played a different role, allowing countries to use the might of state power against their own citizens or subject peoples. In Greece, during the Colonels’ coup of April 1967, the CIA-backed Junta used tanks to kill hundreds of protesting students. In Chile, in September 1973, tanks in effect overturned the ballot boxes that had brought Allende to power. The same story was repeated in Budapest, in Warsaw and in Prague. And it happened in Beijing in June 1989. But in Tiananmen Square a lone Chinese man stepped out in front of a line of tanks that had rolled down the Avenue of Eternal Peace after the massacre of protesting students. The leading ‘40-ton state war machine’ veered to left and right: the young man veered with it. The tank stopped. The commander looked out. He and the young man spoke. When the ‘mechanical ballet’ was over, the young man cycled away. The tanks moved on. The tank commander was demoted for ‘the worldwide shame he had brought on the People’s Liberation Army’ by stopping. But the young man was hailed in the West as democracy’s hero. In the early hours of 28 April 1991, a Soviet t-34 tank that had stood for fifty years in a square in Prague as a memorial to Soviet soldiers was painted shocking pink by David Cerny, a student at the city’s Academy of Applied Arts, and some fellow-students who styled themselves ‘The Neostunners’. When the outraged government had the tank rendered drab again, fifteen Czech parliamentary deputies dressed in blue boiler suits, with an initial on their backs to indicate that they were deputies and were therefore immune from prosecution, painted the tank pink again. Alexander Dubcek was obliged to take a plane to Moscow to apologize to the Soviet authorities. That same year, the year of ‘Desert Storm’ – the perfect textbook war as far as the US military was concerned – Krzystof Wodiczko, a Polish artist living in New York, constructed a tank to ‘defend’ the homeless who had been betrayed and then harried by the city’s first black mayor, the Democrat David Dinkins. The ‘Poliscar’, a flimsy, electronically wired, wigwam-like structure, was described as ‘a war toy for the homeless’ and ‘a robot with a tank-shaped body geared for survival in a police state’ by the art critic of the Village Voice after she had been to see it in a Manhattan gallery. Meanwhile, as the century turned, further south at Fort Knox, top military thinkers were planning ‘the war after the next one’ with the aid of cyberspace. In a simulated world of virtual reality, eager tank soldiers picked up the art of ‘terrain visualization’, familiarizing themselves with the landscape of a distant country so that, when they invaded, they would know it better than the local population. The revolution in technology now meant that the tank could penetrate the fog of war while still maintaining its essential shock element. Perfect lethality – the ability to destroy the enemy without incurring casualties of one’s own – now seemed possible. But the Cold War was over. Even before 9/11, before the war in Iraq, those concerned with the development of military hardware had recognized that while ‘a large dragon had been slain’, we now live in a jungle filled with ‘a bewildering variety of poisonous snakes’. Who knows what role the tank will play in this new landscape? Tank is a far from dispassionate account. Patrick Wright has followed the tank’s tracks and then made connections, visited places talked to people and out of this spun a powerful, individualistic narrative that is both a history of our times and a lesson for the future. Its erudition, elegance, irony and sense of foreboding make it essential reading. ‘Don’t be too painstaking in putting in every rivet,’ Tanks and How to Draw Them, published in 1945, advised. ‘Leave something to the imagination and try to develop the art of suggestion.’ Here the rivets are all in place, but Wright does not, for a moment, fail to suggest the meanings and portents that can be drawn from the progress of this ‘monstrous war machine’.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 5 © Juliet Gardiner 2005

About the contributor

Juliet Gardiner has been writing about various aspects of the Second World War for over a decade but she still only ventures with trepidation into the fringes of that territory claimed by military historians. Her latest book, Wartime: Britain 1939-1945, was published in 2004.