Among the memories of my one visit to Burma almost twenty years ago, the drunken cook who kept falling off our train is probably the most unforgettable. A couple of friends and I had managed to hire a private train from Rangoon to Mandalay. It came complete with a cook who, in between punishing sessions on the local firewater, maintained an erratic flow of fried rice to his three passengers. When no food had arrived for several hours, it was clear he had fallen off again, yet so far he had always managed to reappear in good spirits. The discovery of our bottle of whisky proved a temptation too far. This time he had fallen off, taking the whisky with him, and it was the last we saw of him.

To add to this unexpected encounter, my two friends suddenly embarked on a passionate railway romance, disappearing for hours on end and leaving me to absorb the magical, stupa-studded scenes from the train window on my own. It could have become dreary after a while but fortunately I was not alone. I had Norman Lewis with me. There is no better travelling companion.

Published in 1952, Golden Earth remains one of the most timeless guides to Burma. It is classic Lewis, crammed with incident, humour, observation and detail. There is no mistaking the poise of his prose (Luigi Barzini likened reading it to ‘eating cherries’), nor the empathy that characterizes his dealings with everyone he meets, from monks and policemen to businessmen and lorry drivers. Both Golden Earth and its immediate predecessor, A Dragon Apparent (1951), based on his travels in Indochina, are much more than very fine examples of twentieth-century travel literature. This is profoundly civilized writing in defence of ancient civilizations under imm

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAmong the memories of my one visit to Burma almost twenty years ago, the drunken cook who kept falling off our train is probably the most unforgettable. A couple of friends and I had managed to hire a private train from Rangoon to Mandalay. It came complete with a cook who, in between punishing sessions on the local firewater, maintained an erratic flow of fried rice to his three passengers. When no food had arrived for several hours, it was clear he had fallen off again, yet so far he had always managed to reappear in good spirits. The discovery of our bottle of whisky proved a temptation too far. This time he had fallen off, taking the whisky with him, and it was the last we saw of him.

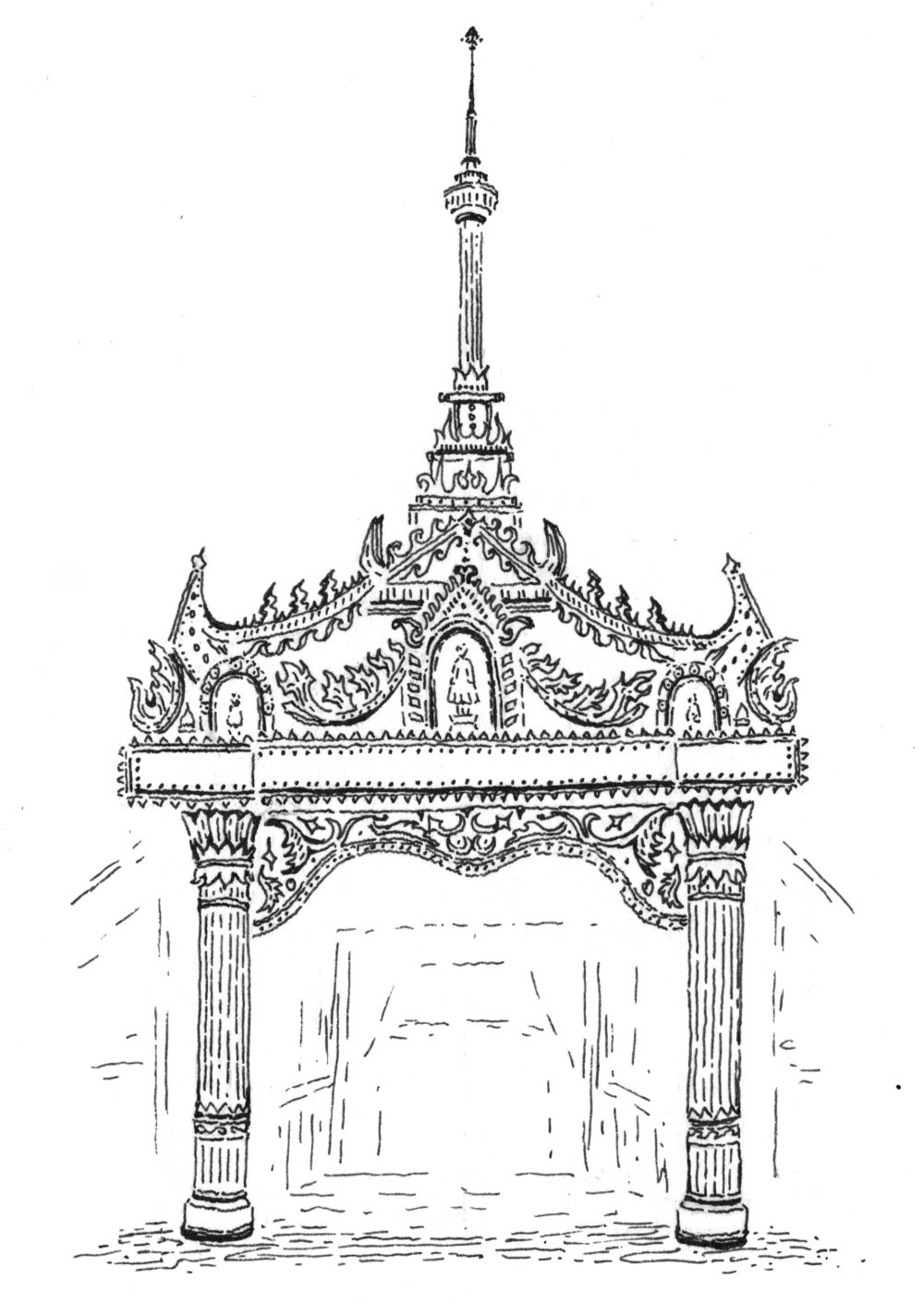

To add to this unexpected encounter, my two friends suddenly embarked on a passionate railway romance, disappearing for hours on end and leaving me to absorb the magical, stupa-studded scenes from the train window on my own. It could have become dreary after a while but fortunately I was not alone. I had Norman Lewis with me. There is no better travelling companion. Published in 1952, Golden Earth remains one of the most timeless guides to Burma. It is classic Lewis, crammed with incident, humour, observation and detail. There is no mistaking the poise of his prose (Luigi Barzini likened reading it to ‘eating cherries’), nor the empathy that characterizes his dealings with everyone he meets, from monks and policemen to businessmen and lorry drivers. Both Golden Earth and its immediate predecessor, A Dragon Apparent (1951), based on his travels in Indochina, are much more than very fine examples of twentieth-century travel literature. This is profoundly civilized writing in defence of ancient civilizations under imminent threat. Like Wilfred Thesiger in the Middle East before the discovery of oil ripped apart its social and physical landscape, and Patrick Leigh Fermor in eastern Europe before the Iron Curtain was drawn across it, Lewis’s work on the Far East stands as a historical monument to a way of life on the brink of destruction. If this all sounds a bit too high-minded and serious, let it be said right away that Lewis is also a hoot. Humour and irony bubble away under the surface, and he has a wicked eye for the absurd. In the Burmese city of Mandalay he takes a room accessed by an outside staircase, at the top of which stands a table with a filthy pitcher of water, and a washbasin:Lewis may have lacked the debonair swagger of Leigh Fermor or the patrician cragginess of Thesiger – the toothbrush moustache suggested an introverted PE teacher rather than a charismatic soldier or spy – but the ability to fade quietly into the background (he once described himself as the ‘semi-invisible man’) was one of his greatest gifts, allowing him to observe everyone and everything around him undisturbed. In any case, there is no mistaking the courage of his journeys in Burma and across Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Lewis courts danger with an understated elegance that puts modern thrill-seekers to shame. The jungle bristles with dacoits attacking trains but time and again he escapes unscathed, without ever making a meal of it. Ignoring virtually every piece of official security advice he is given, he takes planes, trains, trucks, steamers and jalopies, anything to immerse himself ever deeper in the Burmese interior. Speaking of vehicles, this is a writer who, in Cyril Connolly’s memorable line, can make a lorry interesting. And he does plenty of that here. After doing the rounds in Rangoon, Lewis heads north, hitching rides here and there, throwing himself on the whims of a country in which ‘the condition of the soul replaces that of the stock market as a topic for polite conversation’. It is not difficult to guess which one this lacerating critic of America would prefer to discuss. Lewis was always more free spirit than footsie. He is fascinated by the traditional folk religion of nat, or spirit, worship that predates and coexists with Buddhism, follows his nose and witnesses extraordinary ceremonies rarely seen by outsiders. Violence hangs in the air throughout Golden Earth. Reading it more than sixty years after its publication, the approaching civil war and the military dictatorship that sprang from its ruins and even now still holds the reins of power sound a disturbing undertone. Lewis feared the worst. The Burmese have lived it. Conflict is no less menacing in A Dragon Apparent, which opens with Lewis the prose stylist in commanding form. ‘On the morning of the fourth day the dawn light daubed our faces as we came down the skies of Cochin-China . . . With engines throttled back, the plane dropped from sur-Alpine heights in a tremorless glide, settling in the new, morning air of the plains like a dragonfly on the surface of a calm lake.’ For the modern reader it also begins with a harbinger of cataclysmic aggression. Flying into Vietnam with a French Foreign Legion colonel among the passengers, Lewis looks down on an ongoing military operation. Smoke rises from artillery fire below like wisps of incense. ‘Beneath our eyes violence was being done, but we were as detached from it almost as from history. Space, like time, anaesthetizes the imagination.’ And then the killer line – grimly relevant in our age of the drone: ‘One could understand what an aid to untroubled killing the bombing plane must be.’ This, it is worth remembering, was written fifteen years before American bombers vaporized swathes of Vietnam, reducing to ashes the beautiful longhouses of the Moïs people on the central plateau. Saigon disappoints on arrival. It is a French provincial city, with no flavour of the East. Then there is a lovely moment which restores his faith while he surveys the thick swirl of city traffic:Here, at night, a lonely but brilliantly neon-illuminated figure, I performed my toilet, watched incuriously by the Burmese seated at the tables of the tea-shops below. It seemed that Mandalay was without drains. When I asked my Chinese host what was to be done with the waste water, he pointed to the palm-thatched roof of the house below. When I had finally brought myself to accept his implied suggestion, there was a sharp exclamation from within, as if the inmates had never been able entirely to accustom themselves to the procedure.

Try doing that in London. In Lewis’s Indochina the West is an encroachment. He joins a French army tour of Cochin-China for foreign correspondents, a precursor of the modern ‘embed’. Discussing an incident which resulted in the shooting up by the French of a group of peasants who had broken the curfew, the officer in charge attributes the tragedy to ‘the logic of warfare’. The enormously outnumbered French could only hope to retain the upper hand by enforcing regulations with extreme severity, went the argument. Then Lewis plunges in the blade. ‘But this kind of logic is apt not to be so apparent to noncombatants, including newspaper men, who sometimes protest that it was the attitude of the Nazis in occupied territories.’ Travelling in the country of the spirit-worshipping Moïs, he writes that as recently as the early nineteenth century, Europeans considered them articulate animals rather than human beings, and traders sought specimens for zoological collections. While adept at dealing with all manner of internal challenges to the peaceful life of the tribe with rites which invariably require the consumption of significant quantities of alcohol (‘The upright man gives evidence of his ritual adequacy by being drunk as often as possible’), the Moïs are tragically ill-equipped to deal with external threats, none more destructive than the brutal plantation-owners.A bus, sweeping out of a side-street into the main torrent, caught a cyclist, knocked him off and crushed his machine. Both the bus driver and the cyclist were Chinese or Vietnamese, and the bus driver, jumping down from his seat, rushed over to congratulate the cyclist on his lucky escape. Both men were delighted . . . No other incidents of my travels in Indo-China showed up more clearly the fundamental difference of attitude towards life and fortune of the East and the West.

Lewis is just as critical of a sentimental approach to tribal cultures as he is of the downright predatory. Whether he is talking to sympathetic French officers, Viet-Minh guerrillas, animists, emperors or slaves, he manages to pull off a rare trick, combining cool detachment with an acute humanity. The reportage may be as dense as the jungle from which it is prised, but it is rarely impenetrable. The artful simplicity of style, the confidence and curiosity of his voice and the moments of action and well-turned levity whisk you along, admiring the view and envying the prose. One does not have to share Lewis’s politics to enjoy – and, let us be frank, revere – his writing. Anti-Americanism sketches a lively path across his work and one might also raise an eyebrow at the prosperous Westerner deploring Western materialism and ‘the all-eclipsing ideal of the raised standard of living’ that he fears will ruin the East. All that is perfectly reasonable. It matters not that many of the poorest communities in the world, in Asia, Africa and Latin America, fervently wish to improve their standard of living. Lewis’s visceral lament is for the destruction of an older, perhaps romanticized culture, and this is a loss worth mourning. One can only imagine what Lewis would have made of the twenty-first-century invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. It would have been a magnificent read. Policymakers in Washington and London should be thankful he wasn’t around to expose their hubris and deceit.If someone offends the village’s tutelary spirit, the thing can be put right without much trouble. But if a timber-cutting company with a concession comes along and cuts down the banyan tree that contains the spirit, and takes it away, what is to be done? It is the end of the world.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 46 © Justin Marozzi 2015

About the contributor

Justin Marozzi has been living in Mogadishu for a year, reading lots of Lewis, Trollope and Marcus Aurelius to stay sane. His latest book is Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood.