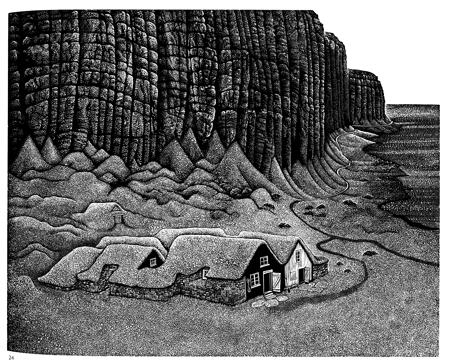

I recently found myself in the excavated ruins of Stöng, a chieftain’s farmhouse in the Icelandic valley of Þjórsárdalur. The manor, along with many neighbouring farms, was abandoned when the volcano Hekla erupted in 1104, covering this Icelandic Pompeii in pumice. Stöng is the best preserved early medieval farmhouse in the Nordic area, with massive turf walls still standing waist-high and a remarkable double-drained social lavatory, which would have accommodated a large gathering. In the main hall the cold slabs of the large central fireplace are visible and I was reminded of the appropriateness of the word ‘window’ – from the Old Norse vindauga, ‘the eye of the wind’ – where the smoke would escape through a single slit in the turf roof.

As I was standing there, imagining the densely walled, fire-lit hall, something stirred in me – a familiar sense of wonder and curiosity about the people who once made their lives here; who created culture in an unforgiving world, charged with the magic that stalked the borders between paganism and Christianity. An image formed in my imagination of a sleeping household, flea-ridden and night-barricaded against the battleaxe-wielding and torch-carrying neighbours of the Icelandic sagas, or perhaps against more unknown, Grendel-like monsters of the mind.

Kristin Lavransdatter, the Nobel Laureate Sigrid Undset’s most celebrated work, brings the medieval North to life in an unparalleled way. Set in fourteenth-century Norway the trilogy of novels was published between 1920 and 1923. Undset was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1928, and by then Kristin Lavransdatter had been translated into many languages and copies sold all over the world.

Born in 1882, Undset grew into a writer at a time when the ‘New Woman’ was starting to view life through the prism of her own being: through her intellect, her eroticism and her desires. She found support in her inner self, her ‘woman�

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI recently found myself in the excavated ruins of Stöng, a chieftain’s farmhouse in the Icelandic valley of Þjórsárdalur. The manor, along with many neighbouring farms, was abandoned when the volcano Hekla erupted in 1104, covering this Icelandic Pompeii in pumice. Stöng is the best preserved early medieval farmhouse in the Nordic area, with massive turf walls still standing waist-high and a remarkable double-drained social lavatory, which would have accommodated a large gathering. In the main hall the cold slabs of the large central fireplace are visible and I was reminded of the appropriateness of the word ‘window’ – from the Old Norse vindauga, ‘the eye of the wind’ – where the smoke would escape through a single slit in the turf roof.

As I was standing there, imagining the densely walled, fire-lit hall, something stirred in me – a familiar sense of wonder and curiosity about the people who once made their lives here; who created culture in an unforgiving world, charged with the magic that stalked the borders between paganism and Christianity. An image formed in my imagination of a sleeping household, flea-ridden and night-barricaded against the battleaxe-wielding and torch-carrying neighbours of the Icelandic sagas, or perhaps against more unknown, Grendel-like monsters of the mind. Kristin Lavransdatter, the Nobel Laureate Sigrid Undset’s most celebrated work, brings the medieval North to life in an unparalleled way. Set in fourteenth-century Norway the trilogy of novels was published between 1920 and 1923. Undset was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1928, and by then Kristin Lavransdatter had been translated into many languages and copies sold all over the world. Born in 1882, Undset grew into a writer at a time when the ‘New Woman’ was starting to view life through the prism of her own being: through her intellect, her eroticism and her desires. She found support in her inner self, her ‘woman’s soul’, rather than in social conventions and norms. Undset was trying to figure out how a woman could shape an independent life in a society formed by men, but, more importantly, she was also working out how to be a writer in this world. For this reason, Undset’s protagonist Kristin Lavransdatter is not a maiden in a male epic but the artist of her own tragedy. Like Undset, I have been fascinated by the early Middle Ages for as long as I can remember. Growing up as a self-sufficient and bookish child in a circumscribed village in southern Sweden I often felt cut out of another time. Merovingian, Visigoth and Viking were words of flux, feud, colour and turmoil that sent ripples through my being. But even then I was wise enough not to let my enthusiasms and secret passions show. My saving grace was my friend Axel, a perpetually tousled boy with dirty hands whose scent – a sandy, greeny blend – I can still recall, along with the eagerness of his breath as he spoke, although I have forgotten the sound of his voice. Between the ages of 4 and 12 we roamed together, exploring our slowly widening world. From our tree-house in Axel’s parents’ garden we planned each new pilgrimage; I conjured up the story and Axel, who was more practical, fashioned the paraphernalia: bows and arrows, a drawbridge and, one early summer evening when we were about 10, a ‘decking of the hall’ of the tree-house with roses, stolen from a local nursery, in order to make our little world beautiful. We often got into trouble. As we ran through the local woods, armed with spears of birch, we were always prepared for danger. We promised to give each other a ship burial, should it come to it, but though we sensed strange and wonderful creatures in the undergrowth we never came across any actual monsters. I had no notion then of being in any way different from Axel, but a few years later my first reading of Kristin Lavransdatter coincided with my being forced into a gender. My friendship with Axel was impossible by then; our naïve appetites were mocked in school and we knew that we would do better to ignore one another. Kristin Lavransdatter launched me on to the cusp of womanhood, manifesting my self through the kind of bewildered feminism that is the inevitable course for anyone who was once a tomboy and who has been expelled from that romance. And so, in my early teens, I lost touch with Axel. Later I became a medieval archaeologist and a writer, if only to be able to continue to roam. That day in Iceland, being blown about by the wings of history in the ruined hall of Stöng, I had the notion that all my years were dissolving, like layers of skin, exposing for a moment the child who was once Axel’s sister-in-arms with a crush on the Dark Ages. This is why, I suppose, I decided to reread Kristin Lavransdatter last summer. It is a 1,000-page novel of love, gender, class, marriage, family, work, honour, duty, ethics and faith, set in the most stunningly depicted emotional, political and natural landscape of southern Norway in 1302–49. As a child, Undset read Njal’s Saga (see SF no. 39), which had a profound effect on her imagination and her linguistic sensitivity. The language of Kristin Lavransdatter reflects an Old Norse register of no-nonsense abruptness and wry stoicism while creating a literary pace of its own, allowing for lyrical – sometimes overwrought – descriptions of the interplay between nature and human sensibility and emotion. Undset’s father, an archaeologist, introduced her to the mindset and material culture of the Middle Ages, which gave her both a scientific approach to the study of the past and a keen eye for historical detail. And so, painstakingly, carefully painting with historical colour while never letting her research show, Undset re-imagined a credible medieval world where she could stage her own struggle as a woman at that time. She had previously written several contemporary novels but it was in her historical fiction, within the framework of a medieval world, that she could expand her re-imagining of a woman’s life course. By the time she started writing Kristin Lavransdatter, she was a divorced mother of three young children. In 1924, after finishing the trilogy, she converted to Catholicism. Her concern with motherhood, her growing spirituality and anti-nihilism during this period are mirrored in Kristin’s development. Kristin Lavransdatter is a love story – but a masterly one that begins, in the first book of the trilogy, with Kristin swiftly breaking her society’s norms of patriarchy, duty and honour in order to give herself over to erotic passion. Undset viewed eroticism – a desire so profound that life would be intolerable if it were not satisfied – as part of the spiritual sphere. Kristin falls, in every way, for the handsome but clearly unsuitable Erlend Nikulaussøn, although her father has already pledged her to the thoroughly decent Simon Darre. When the wedding between Kristin and Erlend is finally allowed to happen, at the end of the first book, it is an excruciating affair, the bridal crown weighing so heavily on Kristin’s head that she can hardly sit upright at the banquet. The second book would delight any agony aunt who recommends ‘working things out’ in a relationship. For Kristin it is about coming to terms with the life that she has chosen for herself. In the last book, after a stubborn battle of wills with Erlend, she finally kicks him out. Although the reader is often tempted to question Erlend’s character and values, we never doubt Kristin’s love for him – to her he does not have to be the best man, her loving him is enough. And it is clear that Erlend, in a patriarchal world, treats Kristin as his equal, which may not always make for great romance. After Erlend’s death (speared in the groin, defending her honour), she retreats to a convent, seeking forgiveness, and dies in the Black Death. I do the trilogy an injustice by trying to summarize it because the delight of these books is not the plot – though as plots go it is lively enough – but rather the universal truths of love between parents and children, friends and lovers. Kristin is a complex, flawed and entirely believable individual with extraordinary dignity and integrity. To get to know her is to understand the nature of love and the workings of human relationships over time. Thankfully, Undset is not didactic. If anything, she shows the reader that to be human means understanding that there is always more than one way to live a life, to love, to be part of a family or a religion. However, to understand this, one has to give in to life, as Fru Aashild, Erland’s kinswoman, explains to Kristin:I’m not foolish enough to complain because I have to be content with sour, watered-down milk now that I’ve drunk up all my wine and ale. Good days can last a long time if one tends to things with care and caution; all sensible people know that. That’s why I think that sensible people have to be satisfied with the good days – for the grandest of days are costly indeed.But there is another aspect to this work, which made my teenage self devour these pages. This has to do with history and fiction – and with historical fiction. Faced with the threat of reality in a place where nothing seemed to happen (unless Axel and I created our own history), Kristin’s story mystified the reality of adulthood, which I was inevitably entering, and rendered it interesting. Like any great historical novelist Undset showed the reader that people in the past were like us – it is just the circumstances of society that change. And so the inquiry into other worlds may help us to widen the narrow circumstances of our own lives, our particular reality, by encompassing a shared humanity.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 61 © Karin Altenberg 2019

About the contributor

Karin Altenberg is currently writing a novel set in a time and place she knows little about. As a result she’s trying very hard to live in the present, knowing that the good old days never really happened.