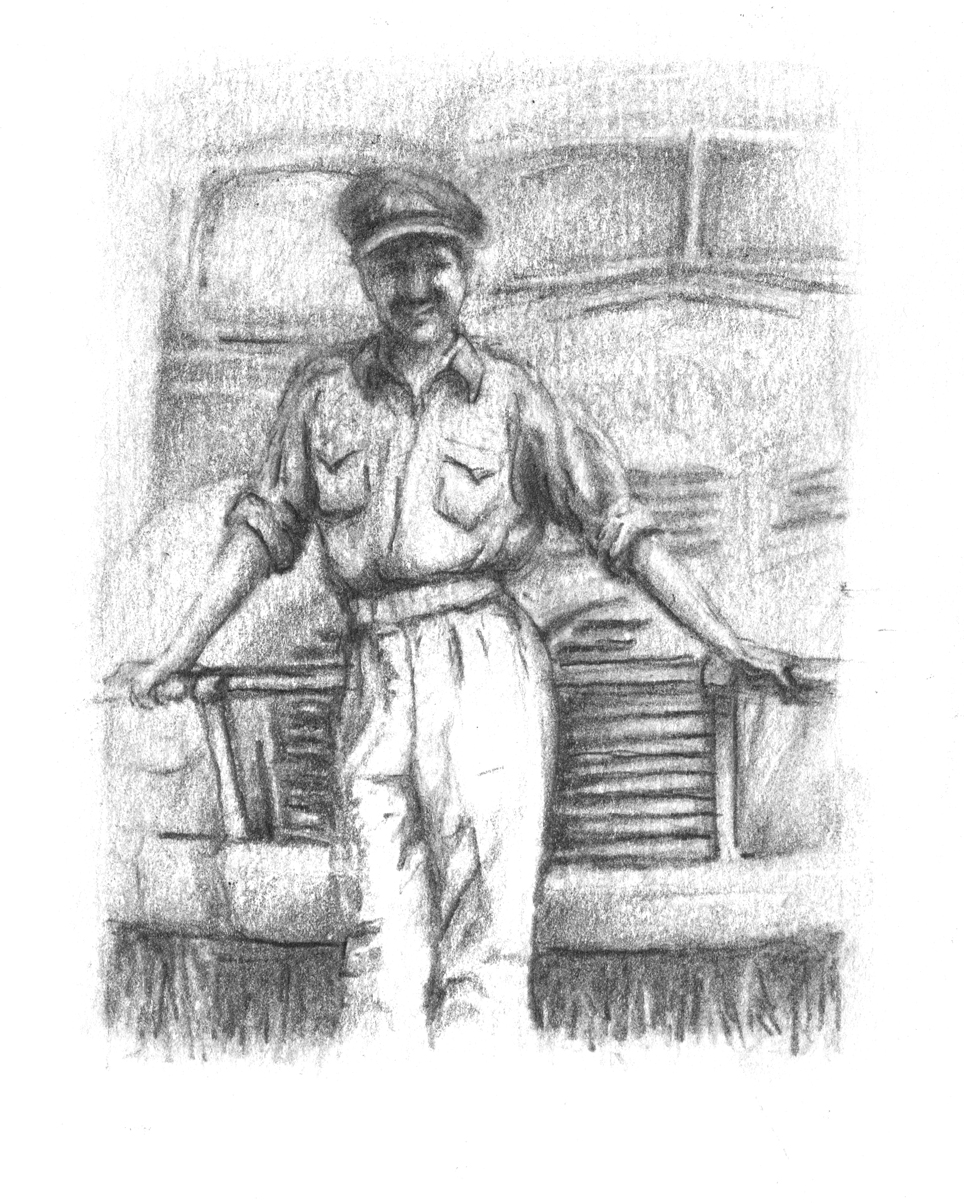

Alamein to Zem Zem bears as a frontispiece a photograph of its author. Keith Douglas leans against the bonnet of a lorry, arms spread out, smiling. He wears khaki shirt and trousers, officer’s cap. He is 22 but looks older. His moustache contributes to that effect; a moustache seems to have been mandatory officer equipment in the Libyan campaign of the 1940s, judging by other contemporary photos.

Douglas arrived in the Middle East in 1941, managed to get to the front in time for the second battle at Alamein, advanced west after the defeat of Rommel’s forces, was wounded, recuperated in Cairo and returned to the Tunisian front. On 9 June 1944, three days after the D-Day landings, he was killed in Normandy, aged 24.

The Second World War did not spawn poets in the way the First World War did. Keith Douglas is one of few, and a leading name. The Complete Poems of Keith Douglas (edited by Desmond Graham) is a slim volume, swollen by his juvenilia and by poems of which several drafts are given. He had so little time: a burst of creativity in 1942 and 1943, when action as a tank commander allowed, and that was that. He had hardly found his voice as a poet, but there are some memorable poems, and lines that stick in the mind, images that compel: ‘On scrub and sand the dead men wriggle/in their dowdy clothes’.

There is much death in the poetry, and graphic death imagery in the pen-and-ink drawings with which Douglas illustrated Alamein to Zem Zem – he was a talented draughtsman: a contorted corpse in the sand, bodies spilling from a bombed lorry. But there is also, in both the poems and the narrative, exuberance, a keen and maverick appreciation of the physical world, wit and humour, and evidence of a roving imagination.

And, on the evidence of Alamein to Zem Zem, he was a remarkable prose writer. Written in the immediate aftermath of the experiences, with, it would seem, little structural con

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAlamein to Zem Zem bears as a frontispiece a photograph of its author. Keith Douglas leans against the bonnet of a lorry, arms spread out, smiling. He wears khaki shirt and trousers, officer’s cap. He is 22 but looks older. His moustache contributes to that effect; a moustache seems to have been mandatory officer equipment in the Libyan campaign of the 1940s, judging by other contemporary photos.

Douglas arrived in the Middle East in 1941, managed to get to the front in time for the second battle at Alamein, advanced west after the defeat of Rommel’s forces, was wounded, recuperated in Cairo and returned to the Tunisian front. On 9 June 1944, three days after the D-Day landings, he was killed in Normandy, aged 24. The Second World War did not spawn poets in the way the First World War did. Keith Douglas is one of few, and a leading name. The Complete Poems of Keith Douglas (edited by Desmond Graham) is a slim volume, swollen by his juvenilia and by poems of which several drafts are given. He had so little time: a burst of creativity in 1942 and 1943, when action as a tank commander allowed, and that was that. He had hardly found his voice as a poet, but there are some memorable poems, and lines that stick in the mind, images that compel: ‘On scrub and sand the dead men wriggle/in their dowdy clothes’. There is much death in the poetry, and graphic death imagery in the pen-and-ink drawings with which Douglas illustrated Alamein to Zem Zem – he was a talented draughtsman: a contorted corpse in the sand, bodies spilling from a bombed lorry. But there is also, in both the poems and the narrative, exuberance, a keen and maverick appreciation of the physical world, wit and humour, and evidence of a roving imagination. And, on the evidence of Alamein to Zem Zem, he was a remarkable prose writer. Written in the immediate aftermath of the experiences, with, it would seem, little structural consideration or revision, it is an extraordinary piece of battle reportage. So intense and detailed is the account that you read with absolute absorption, as though you too took part in these confusing, terrifying tank skirmishes. Desert warfare is like no other; the only analogy is naval warfare – the same situation of empty space in which opposing forces have to contend not only with each other but with the hostility of the environment; no civilian occupants to be considered, but no natural resources. In the desert, the armies faced heat, cold (yes, at night), absence of water, distances. The armies’ lifeblood was petrol. Ironically, oil was also what it was all about. Hitler’s drive into North Africa was aimed through Egypt, Palestine (as it then was), on and up into the oilfields of Iraq and Iran. At the point when Douglas joined his regiment, the Nottingham Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry, Rommel’s army and the Allied forces had been pushing each other to and fro across Libya for nearly two years. Rommel was now in the ascendant, having swept the Allies back into Egypt where things had stalled at the Battle of Alam Halfa, the precursor to Alamein – the time at which Churchill, impatient with the leadership of General Auchinleck, had brought in Bernard Montgomery. ‘I observed these battles partly as an exhibition,’ Douglas wrote, ‘that is to say I went through them partly like a visitor from the country going to a great show . . . When I could order my thoughts I looked for more significant things than appearances; I still looked – I cannot avoid it – for something decorative, poetic or dramatic.’ He did indeed; the account is spiced with arresting detail, and above all with a pervading immediacy, the individual narratives of an incident, of a tank engagement, of some side-show during an action. He describes, at one point during the Alamein offensive, a diversion when advancing infantry had pointed out German snipers sheltering behind derelict tanks: ‘“You see them Jerry derelicts over there, them two? . . . I should have thought you could run over the buggers with this,” he said, patting the tank.’ Douglas describes his advance, the ensuing confusion as his machine-gun jams, the shock when the snipers turn out to be a whole contingent, whom he takes prisoner: ‘The figures of soldiers continued to rise from the earth, as though dragons’ teeth had been sown there.’ There is much dialogue. Language lifts from the text, as though you are eavesdropping on that time and place. Exchanges with fellow officers, exchanges with his tank crew, the arcane speech of wireless communication during battle: ‘Nuts Three, Nuts Three, I still can’t see you. Conform. Conform. Off.’ Language is a reminder of the rigid class distinctions of the day, the gulf between officers and men. The Sherwood Rangers had been a cavalry regiment. Some of Douglas’s colleagues were wealthy rural gentry, hunting and shooting men, almost as alien to him, from a far from prosperous middle-class background, as to the men they commanded. He was fascinated by personalities, especially that of his commanding officer, who he calls Piccadilly Jim and with whom he has the occasional run-in, provoked as much, one suspects, by Douglas’s natural intransigence and independence of spirit as by any perverse orders implied by Douglas, who could clearly be difficult – courageous, opportunist and awkward. Piccadilly Jim was killed in Tunisia. It is this attention to detail that distinguishes Alamein to Zem Zem, making it testimony to what it was like to be in the western desert in 1942 quite as much as an eye-witness account of what happened there. What it was like in terms of men, from laconic former cavalry officers to shit-scared 19-year-olds. What it was like in terms of the baggage carried, the food eaten, the punishing conditions. Douglas lists the belongings he took with him into battle: food supplies including tea and sugar stored in a pair of clean socks, tins of coffee, Oxo cubes, along with a flask of whisky, washing and shaving kit, writing-paper, a camera and a Penguin Shakespeare Sonnets. The Eighth Army was fuelled by bully (beef), tinned meat and veg, tinned potatoes, jam, Palestinian marmalade, oatmeal biscuits and a generous supply of strong, sweet tea. And, when the opportunity arose, goods looted from the retreating enemy; there was intense interest in looting, from the acquisition of Luger pistols and binoculars to treasured chocolate and brandy. The water ration was half a gallon a day per man, for washing, cooking and drinking.The routines are described: ‘Every tank must be filled with fuel, rations, current and emergency, water and ammunition. Lorries jolted and lurched slowly round from tank to tank, distributing their wares.’ This was an existence of daily endurance, boredom even, punctuated by episodes of terror and, indeed, exhilaration. It is these episodes that are so gripping. One wonders how soon afterwards Douglas got something down on paper, how he retained the immediacy. There is the blow-by-blow account of an engagement when his tank troop is stalking an enemy position in a valley (in Tunisia now), approaching what he thinks to be a gun-site vacated by the enemy and realizing that it is in fact the turret of a heavy tank: ‘This tank’s gun would send a solid shot through my turret and out the other side at twenty hundred, and he was not a hundred and fifty yards away.’ Well, to find out what happened next you will have to visit Alamein to Zem Zem. It is one of those books that seems much longer than it really is. Into 152 pages so much is packed – people, places, action, inaction. And, crucially, a vivid impression of Douglas himself, his strong personality, his seriousness about his poetry, his sharp eye for the circumstances into which he had been flung. His interest in girls; various young women in Palestine and Cairo feature, mostly rather unsatisfactorily – he had trouble with girls. I can never lose sight of how young he was; the language of the book sounds sophisticated – ironical and occasionally acerbic – but this is a 22-year-old, fresh from boarding-school and Oxford. You shot to maturity, I suppose, in Libya. Just as you had to learn in a matter of weeks how a tank functions, how to command a tank troop, so you had to learn to confront, daily, the sight of death and the possibility that yours could be next. ‘The most impressive thing about the dead is their triumphant silence, proof against anything in the world.’ That is a startling piece of writing; it illuminates, for those of us who have never been thus exposed to death, and it is also the perception of someone who may be young but who has the wisdoms of accelerated experience. Alamein to Zem Zem charts, in a sense, the development of a mind. It is hasty writing, seizing the hour; and its power, and fascination, is that it combines thoughts and observations like that one with the prosaic but compelling descriptive commentary that takes the story forward:Nine in every twelve men were covered with inflamed, swollen and painful sores, on hands, faces or legs, which took weeks or months to heal and left deep, red scars. Every man was coloured under his skin with dirt, and eyes were bloodshot with continual dust and sandstorms. But everyone shaved or washed, at least superficially, at reasonable intervals.

Douglas starts his story in Egypt, and ends it in Tunisia, with the German forces in defeat: ‘And tomorrow, we said, we’ll get every vehicle we can find, and go out over the whole ground we beat them on, and bring in more loot than we’ve ever seen.’ That’s it, the close of the account, and somehow the appropriate note of panache. But, for the reader, there is the accompanying sadness: we know what is to come. Douglas says that he assumed he was going to die at Alamein. Later, at a moment of crisis, he records being more unnerved by the prospect of capture than of being shot. Alamein to Zem Zem is the remarkable record of how it was to be young, and faced with such thoughts, and such experiences. I spent my childhood in Egypt and was 9 at the time of the Battle of Alamein. Many Eighth Army officers on leave visited my home outside Cairo (which had allegedly been earmarked as Rommel’s weekend retreat). Keith Douglas was not among them, but when I first read Alamein to Zem Zem he seemed entirely familiar.On the main tracks, marked with the crude replicas of a hat, a bottle and a boat, cut out of petrol tins, lorries appeared like ships, plunging their bows into drifts of dust and rearing up suddenly over crests like waves.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 39 © Penelope Lively 2013

About the contributor

Penelope Lively’s most recent novel, How It All Began, is now available in paperback.