At midnight on New Year’s Eve 2012, as fireworks burst over Hyde Park, I was propped up in bed with a paperback feeling a terrific failure. The book was Charles Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge. I was 459 pages in and nowhere near finishing. Even if I’d read until dawn I would have been hard-pressed to manage the last 400 pages. I struggled on for another hour or so and then turned out the light.

A year before it had all seemed so possible. That Christmas, the books pages had been full of the approaching Dickens bicentenary. Literary figures nominated their favourite characters; there were advertisements for exhibitions, lectures and night walks through London; the BBC lined up its costume dramas. I felt embarrassed that I’d read so little Dickens – nothing since Great Expectations at school and a failed attempt at Little Dorrit at university. And so, in those dull, slow days between Christmas and January, I made a New Year’s resolution – to read all Dickens’s novels by midnight on 31 December 2012.

It seemed a daunting but not impossible task. Fifteen books (excluding Great Expectations) would mean one every twenty-four days. The shorter ones – Hard Times and A Christmas Carol – would take less than that, creating more time for the doorstops: Little Dorrit, Bleak House and Our Mutual Friend. The problem was that I wasn’t someone with time on my hands. I work twelve-hour days on the features desk of a national newspaper. Long evenings on the sofa with a good book are all too rare.

But gradually the novels became an obsession. Coming down with a bout of flu or a stomach upset was a blessing. ‘Hurrah!’ I’d think. ‘Forty-eight hours in bed to break the back of David Copperfield.’ I longed for trains to be held up and flights delayed so that I could press on with, say, the Venice section of Little Dorrit. Enough of prunes and prisms o

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign in orAt midnight on New Year’s Eve 2012, as fireworks burst over Hyde Park, I was propped up in bed with a paperback feeling a terrific failure. The book was Charles Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge. I was 459 pages in and nowhere near finishing. Even if I’d read until dawn I would have been hard-pressed to manage the last 400 pages. I struggled on for another hour or so and then turned out the light.

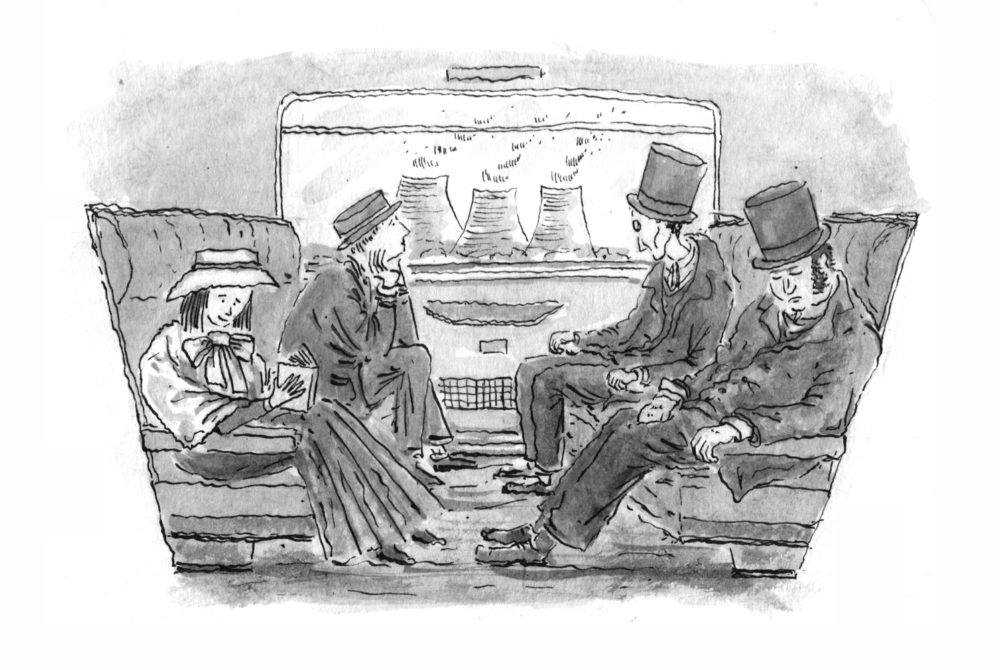

A year before it had all seemed so possible. That Christmas, the books pages had been full of the approaching Dickens bicentenary. Literary figures nominated their favourite characters; there were advertisements for exhibitions, lectures and night walks through London; the BBC lined up its costume dramas. I felt embarrassed that I’d read so little Dickens – nothing since Great Expectations at school and a failed attempt at Little Dorrit at university. And so, in those dull, slow days between Christmas and January, I made a New Year’s resolution – to read all Dickens’s novels by midnight on 31 December 2012. It seemed a daunting but not impossible task. Fifteen books (excluding Great Expectations) would mean one every twenty-four days. The shorter ones – Hard Times and A Christmas Carol – would take less than that, creating more time for the doorstops: Little Dorrit, Bleak House and Our Mutual Friend. The problem was that I wasn’t someone with time on my hands. I work twelve-hour days on the features desk of a national newspaper. Long evenings on the sofa with a good book are all too rare. But gradually the novels became an obsession. Coming down with a bout of flu or a stomach upset was a blessing. ‘Hurrah!’ I’d think. ‘Forty-eight hours in bed to break the back of David Copperfield.’ I longed for trains to be held up and flights delayed so that I could press on with, say, the Venice section of Little Dorrit. Enough of prunes and prisms on the Rialto, I wanted Amy reunited with Mr Clennam in Bleeding Heart Yard. Friends were amused, incredulous, indulgent and towards the end, I fear, bored. But during those early, chilly days of 2012, the whole idea seemed wonderfully possible. In retrospect, I wonder whether I shouldn’t have started at the beginning with the chummy, ruddy-cheeked Pickwick Papers and read steadily in order, ending with the unfinished, opium-soaked whodunit The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Instead, I started with the longest (going by the page numbers in the Penguin Classics editions), Bleak House. It felt right for the time of year – a murky, clammy book for a murky, clammy January. Pickwick would have been too hearty, too out-of-doors. Bleak House shivers in the dank alleys of Tom-All-Alone’s or sweats unhealthily in close, overheated rooms, choked with soot and claustrophobia. Progress on David Copperfield, which followed Bleak House, was greatly helped by a streaming cold. I spent four days in bed which got me from the beached ship-cottage at Yarmouth, via Salem House School, to Canterbury (‘Janet! Donkeys!’) and my introduction to ’umble Uriah Heep. By the time I went back to work, there were just a few hundred pages to go. Nicholas Nickleby came next, then Oliver Twist (another weekend in bed with a cold) and A Tale of Two Cities. I was soaring. Better than that, I was enjoying myself. I loved Dickens’s exuberance, his purple descriptive passages, his fulminations on Chancery, Whitehall and the City, his sprawling casts of characters. I often felt I could have done with a list of dramatis personae to keep track of them all: Miss Mowcher, a dwarf hairdresser; Steerforth, a golden-haired seducer; Mrs Gummidge, a lone lorn creetur. Nothing is ever lean or skimped in Dickens. From time to time, I found myself thinking that a merciless editor would have cut each book by 200-odd pages. But it is the flights of fancy, the wild excursions, the unnecessary detours that make Dickens what he is. The chapters featuring Mrs Nickleby’s gentleman neighbour who attempts to woo her by throwing first cucumbers and then ‘a shower of onions, turnip-radishes, and other small vegetables’ over the garden wall, do little to advance the plot – but, oh, how glorious! As I got into my stride, however, I found that it wasn’t so much Dickens’s excess that I enjoyed as his neatness. No matter how chaotic the plot seemed at p.650 – families scattered to the winds, hero penniless and disgraced, heroine struck down with smallpox – by p.980, all would be satisfactorily resolved, the threads gathered up, the mysteries explained. But perhaps it was Dickens’s attention to his lesser characters, the understudies and supporting cast, that gave me most pleasure. How wonderful to see Nickleby’s portrait miniaturist Miss La Creevy (who a more neglectful novelist might have left a spinster) finally married to the kindly clerk Tim Linkwater. And to hear of Captain Cuttle, at the end of Dombey and Son, set up in his own shop with his name above the door and at last able to open the bottle of Madeira he’d been saving for just such an occasion. And there could be no more companionable guide. Dickens, famously a prodigious walker, often covered as many as 30 miles in a day. This was how I imagined him as a narrator – bustling you along, pointing out a scene of interest here, hurrying you past a plot device there, and telling you that there simply wasn’t time for a pie and porter in Covent Garden because we were due a dénouement in Twickenham at half past seven. But then in May, dashing perhaps a little too confidently through the streets of Dickens’s London, I tripped and fell. A week’s holiday coincided with a surprise heatwave. The thought of another thousand-pager was more than I could take. It was too warm, too stupefying to concentrate for more than a few pages at a time. So sitting on the fire escape – the closest anyone in a sixth-floor flat comes to a garden – I started on Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. If I had confined this diversion to those five days, I might have got away with it. But I was seized by a strange mania. If I could read the whole of Dickens, why not the whole of Holmes? Better still, the whole of Conan Doyle? I was two books into his Professor Challenger trilogy when I came to my senses. After nearly three weeks of Holmes and Challenger, I was horribly off schedule. It was June and I still had ten books to go. Hard Times is mercifully short. I managed it over a weekend in Oxfordshire with a useful delay at Didcot Parkway on the train back to London: long enough to see Stephen Blackpool raised from the mine shaft and the odious Mrs Sparsit get her comeuppance. When it came to The Pickwick Papers, I confess I cheated. Whenever Mr Pickwick or one of his travelling companions launched into a long, boozy fireside story that didn’t much advance the plot, I skipped ahead. Sticklers may wince, but time was against me. The Old Curiosity Shop wasn’t a great favourite, but it had its moments. I certainly haven’t looked at a prawn in the same way since reading Dickens’s description of the monstrous Quilp devouring ‘gigantic ones with the heads and tails still on’. And while Little Nell’s fairy-tale goodness grated, my heart went out to the even littler Marchioness, confined below stairs and never once tasting more than a sip of beer. In September I retreated to bed with a hacking cough and Martin Chuzzlewit. The American section left me cold – Dickens didn’t seem to be Dickens once he left England. Chuzzlewit in the malarial swamps of America, the Paris sections in A Tale of Two Cities, the Dorrits in Venice – all had me hankering to get back to London and the slime and ooze and filth of the Thames. I was flagging, but Little Dorrit soon revived me. If I had thought I cared about Nicholas and Madeline, David and Agnes, Martin and Mary, those feelings were nothing compared to my attachment to Arthur and Amy and their unlikely Cupid, the puff-puff-puffing Mr Pancks. Towards the end of the novel, when Amy tells him ‘I was never rich before, I was never proud before, I was never happy before’, I was in tears. (Though I wept even more helplessly at the death of Jo the Crossing Sweeper – ‘It’s turned wery dark, sir. Is there any light a-coming?’ – in Bleak House.) By the beginning of November (chilly and wet again, just right for the Southwark damp of Our Mutual Friend) I began to think that I might really do it. Mr Boffin was making progress with his Decline and Fall, Silas Wegg was peg-leg deep in dust heaps, and the pouting Bella had been installed in a ‘spanker’ of a house in a smart part of town. Once Eugene Wrayburn had been knocked senseless into Plashwater Weir Mill Lock there would be just A Christmas Carol, Dombey and Son, Barnaby Rudge and Edwin Drood to go. Then I started to panic. What would I do with no more novels to tick off my list? No more heroes lost at sea and found again just in time to be married to their childhood sweethearts. No more wills to be fought over. No more rapacious uncles to get their just deserts. When a friend suggested that after I’d come to the end of Dickens I should try Vikram Seth, often called ‘the Dickens of India’, I heard myself saying that I wasn’t sure I’d quite done Our Mutual Friend justice the first time around. And I’d read Hard Times in a bit of a hurry. And I really ought to reread Great Expectations. . . She put her head in her hands. I read A Christmas Carol in early December and Dombey and Son over Christmas, bolting meals and barely speaking to my family. On 29 December, I went back to work. Three days left and still the whole of Barnaby Rudge and Edwin Drood to go. There was little hope now of meeting my deadline, but I did my best. Two hundred-odd pages of Barnaby Rudge after work that day, another hundred or so the night after. On New Year’s Eve I’d got to just over the halfway point when the chimes caught up with me. On New Year’s Day I walked to work feeling dismal. But then, as friends and colleagues filtered back to London, I cheered up. I hadn’t done too badly. Some people don’t manage the novels of Dickens in a lifetime, let alone a year. I finished Barnaby Rudge at a leisurely pace and read Edwin Drood over a weekend at the end of February. Yet far from feeling released, I felt bereaved. I’d lost a great friend. Dickens had become a part of my life – the weight of a Chuzzlewit in my handbag, lugged around in the hope of five minutes’ reading at a bus stop; the pile of Penguins on the bedside table. I suppose I could now read all of Trollope or Hardy or Zola. There’s certainly still plenty of Conan Doyle to get through. But I do find myself thinking that I really shouldn’t have cheated on Pickwick Papers. And I’m not sure I can remember who Sir Barnett Skettles is or which book the Spottletoes belong to. Perhaps I should read just a couple of them again . . .Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 41 © Laura Freeman 2014

About the contributor

Laura Freeman has taken up Dickens’s habit of London night-walking. ‘A good great-coat and a good woollen neck-shawl’ have indeed proved indispensable when tramping from Waterloo to Bayswater in January.