‘It’s like Pokémon,’ said my husband Andy, standing in the cool of a church in San Gimignano on our very hot honeymoon. And yes, I suppose saint-spotting is a bit like Pokémon, the creature-collecting game invented by Nintendo in the Nineties. Slogan: ‘Gotta catch ’em all.’

We weren’t hunting for Pikachus or Bulbasaurs, but for St Catherines and St Antony Abbots in fresco cycles and altarpiece panels. Catherine you’ll know by her wheel, instrument of her martyrdom, St Antony by his bell and his pig. A friend speaks fondly of childhood holidays with his church-crawling parents. He and his twin sister would be sent off to play saintly bingo. Could they find a St John the Baptist (lamb and sheepskin gilet), a Mary Magdalene (jar of unguent), an Apollonia (tooth and pincers)? Off they would go round cloisters, into side-chapels, standing on tiptoe for a better look at stained-glass windows. As with Pokémon, they knew their saints by their markers. Gotta catch ’em all.

I came to the game later. It would be nice to tell you of a Road to Damascus moment (see PAUL, the conversion of), of picking up a copy of Hall’s Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art from a shelf in a second-hand bookshop and being blinded by the light of sudden art-historical revelation. In truth, Hall’s was a set book on a university reading list. I ordered a copy and put it in a box in the boot of a car bound for Freshers’ Week. No one sits down to read a dictionary. I’d look at it as and when.

But Hall’s isn’t a dictionary, alphabetically arranged though it is. I was going to say that it’s more of a gazetteer, a guide to people, paintings and putti. But gazetteer isn’t quite right either. Too workaday. Hall’s is more like a grimoire – a magician’s manual for invoking strange beings and things. Hammer, Hand, Hare, Harp, Harpy, Harrowing of Hell, Harvest, Hat, Hatchet . . . Such summonings can be glorious

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign in‘It’s like Pokémon,’ said my husband Andy, standing in the cool of a church in San Gimignano on our very hot honeymoon. And yes, I suppose saint-spotting is a bit like Pokémon, the creature-collecting game invented by Nintendo in the Nineties. Slogan: ‘Gotta catch ’em all.’

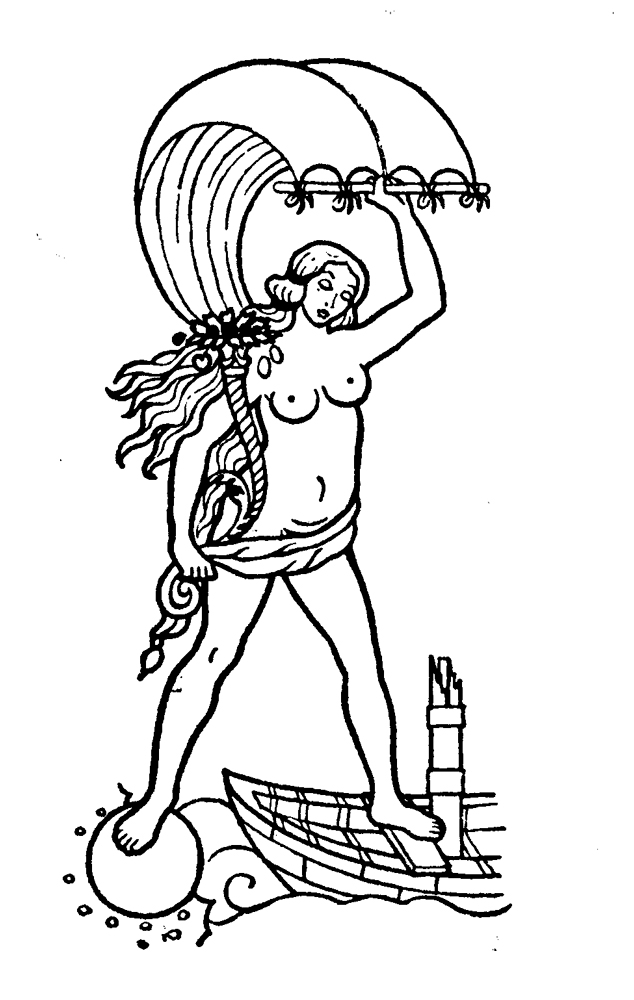

We weren’t hunting for Pikachus or Bulbasaurs, but for St Catherines and St Antony Abbots in fresco cycles and altarpiece panels. Catherine you’ll know by her wheel, instrument of her martyrdom, St Antony by his bell and his pig. A friend speaks fondly of childhood holidays with his church-crawling parents. He and his twin sister would be sent off to play saintly bingo. Could they find a St John the Baptist (lamb and sheepskin gilet), a Mary Magdalene (jar of unguent), an Apollonia (tooth and pincers)? Off they would go round cloisters, into side-chapels, standing on tiptoe for a better look at stained-glass windows. As with Pokémon, they knew their saints by their markers. Gotta catch ’em all. I came to the game later. It would be nice to tell you of a Road to Damascus moment (see PAUL, the conversion of), of picking up a copy of Hall’s Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art from a shelf in a second-hand bookshop and being blinded by the light of sudden art-historical revelation. In truth, Hall’s was a set book on a university reading list. I ordered a copy and put it in a box in the boot of a car bound for Freshers’ Week. No one sits down to read a dictionary. I’d look at it as and when. But Hall’s isn’t a dictionary, alphabetically arranged though it is. I was going to say that it’s more of a gazetteer, a guide to people, paintings and putti. But gazetteer isn’t quite right either. Too workaday. Hall’s is more like a grimoire – a magician’s manual for invoking strange beings and things. Hammer, Hand, Hare, Harp, Harpy, Harrowing of Hell, Harvest, Hat, Hatchet . . . Such summonings can be glorious – a Harp appears commonly among the instruments played by concerts of angels – and they can be gory. One may find a Hatchet ‘embedded in the skull of Dominican monk, the attribute of PETER MARTYR.’ Hall’s sets the hares running. It’s not just for Christmas presents and it’s certainly not just for reference. It’s a dictionary you really do read. When I can’t sleep, I open it at random and see where the pages fall. Peace, Peach, Peacock, Pearl, Pegasus, Pelias (king of Iolcus, see JASON; MEDEA), Pelican, ‘Pellit et attrahit’ (see WINDS), Pelt, Pen and inkhorn (see WRITER) . . . And if you think I chose that page deliberately, so that I’d land on pen and inkhorn and a point about writing, I didn’t. Serendipity. With Hall, there’s a Peach on every page. It’s not a book you need read in order, working your way down the list. Better to let yourself be blown off course. Interest piqued by ‘Pellit et attrahit’? Here it is under Winds: ‘A bodiless wind god is the impresa of Ranuccio Farnese, Duke of Parma (1569–1622), with the motto “Pellit et attrahit” – “He drives off (evil) and attracts (good)”. (Farnese Palace, Rome.) See also SAIL.’ Sail. The attribute of FORTUNE, both in antiquity and the Renaissance, because she is inconstant like the wind; also of VENUS, who was born of the sea. A sail-like drapery billowing over the head of a sea-nymph, see GALATEA. See also TORTOISE. Tortoise, with a sail on its back, was the impresa of Cosimo de’ Medici (1369–1464). The accompanying motto was ‘Festina lente’ – ‘Make haste slowly’, that is be slow but sure. Slow but sure was the James Hall way. He worked steadily, tirelessly at his Dictionary over many years. His research was rewarded. Published in 1974, Hall’s Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art is still in print and has been translated into twelve languages. My paperback edition is introduced by Kenneth Clark, otherwise Lord Clark of Civilisation. He begins by informing us that fifty years ago (the 1920s) we were told that ‘subject’ no longer mattered in art. It was all about form, or ‘significant form’ as it was then fashionably called. This was a curious aberration of criticism, because all artists from the cave painters onwards, had attached great importance to their subject matter; Giotto, Giovanni Bellini, Titian, Michelangelo, Poussin or Rembrandt would have thought it incredible that so absurd a doctrine could have gained currency. Worse, in that same fifty years, the average man had become progressively less able to recognize the subjects or understand the meaning of the works of art of the past. Fewer people had read the classics of Greek and Roman literature, and relatively few people read the Bible with the same diligence that their parents had done. It comes as a shock to an elderly man to find how many biblical references have become completely incomprehensible to the present generation. Clark would be more shocked still at the incomprehension of my generation of millennials when presented with a painting of, say, The Visitation (the pregnant Virgin Mary and her cousin Elizabeth meeting bump-to-bump). ‘What the ordinary traveller with an interest in art and a modicum of curiosity requires is a book which will tell him the meaning of subjects which every amateur would have recognized from the middle ages down to the late eighteenth century.’ Such a book is Hall’s. James Hall was an ordinary sort of traveller with an extraordinary turn of mind. He was born on 8 July 1918, in Norton, near Baldock, Hertfordshire, where his father owned a farm. He had little formal education, left school at 17, and went into commercial advertising. When the war came, he successfully claimed exemption from military service as a conscientious objector. In 1940, he volunteered for the Friends’ Ambulance Service and served with a military mobile hospital in North Africa and then Syria. After the war, he worked for the publishers J. M. Dent, later becoming production manager at the Dent head office in Bedford Street, Covent Garden, where he supervised the publication of the Everyman’s Library. Motto: ‘I will go with thee, and be thy guide/ In thy most need go by thy side.’ In his spare time Hall taught himself French, Italian and Spanish with the help of language-learning vinyl records. When lunch hours allowed, he would visit the National Gallery and find himself puzzling over saints and their attributes. Hall looked for a book that would explain why that lady was bearing her breasts on a plate (poor, poor St Agatha) and what that chap was doing writing books in the desert (St Jerome, with lion and pen). Finding no such volume, he set out, Jerome-like, to write it himself. He didn’t stick to saints. In Hall’s you’ll find gods and monsters, heroes and hedgehogs, Polyphemus the one-eyed cyclops and Pasiphae ‘who conceived a violent and unnatural passion for a bull’. Hall would get up at 6 a.m. to work for an hour at home in Harpenden before taking a train into London. After a day at Dent, he would pick up again in the evenings. Weekends he spent in the Reading Room at the British Museum, in the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum or at the London Library. Remember, this was in the days before search engines or digital library catalogues. It took Hall years to produce what he modestly called The Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art. His publisher, John Murray, rightly rechristened it Hall’s Dictionary. Kenneth Clark wrote that he would recommend Hall’s ‘to anyone who wishes to increase his interest and pleasure in visiting a picture gallery or turning over the illustrations of a book on art’. Reading Hall’s is a pleasure in itself, but Clark is correct: far better is the pleasure it brings to looking at pictures. In the Discworld books Thud! and Making Money, Terry Pratchett has his characters visit the collection of the Ankh Morpork city art gallery which contains such masterpieces as Carvatti’s Three Large Pink Women and One Piece of Gauze, Sir Robert Cuspidor’s Wagon Stuck in River, Mauvaise’s sculpture Man with Big Figleaf and an unrivalled collection of pictures of women with not many clothes on, posing by an urn. When looking at pictures, there is, of course, no need to know the narrative. You could simply admire the brushstrokes, the chiaroscuro, the contrapposto, the sfumato, the fine handling of paint in Man and Woman Naked with Tree Snake, Large Pink Woman with Bull by the Sea or the famous Haircut by Candlelight. But you might get rather more out of the ‘Temptation’, the ‘Rape of Europa’ and ‘Samson and Delilah’ if you knew who’s who and what’s what. Perhaps what it boils down is this: I like stories. I like them a great deal more than I like form, significant or otherwise. Hall’s is full of them. From the Old and New Testaments, from the Iliad and the Odyssey, from Ariosto and Ovid. Stories apocryphal, stories mythological, stories miraculous and stories diabolical. Stories about a man and his three-headed dog. Hall’s has it all. When Andy and I were struggling for baby names last year, I found myself flicking through Hall’s. Aeneas? Angelica? Demeter? Dorothea? Elmo? Euphemia? Iphigenia? (Effie? Iffie?). ‘Alice is nice,’ Andy would counter. Or Anne. Or Josh. Or Rob. Or any other name less tragic, Greek or polysyllabic. As the due date drew nearer, we both warmed to Arthur, if a boy, while I petitioned for Iris, my grandmother’s name, if a girl. I consulted Hall’s to check that Iris was not an ancient goddess of strife. Happily, not. Iris in Greek mythology was the goddess who personified the rainbow, on which she descended to earth as messenger of the gods. Juno sent Iris to release the soul of Dido when she died on the pyre. She was sent to rouse the sleeping Morpheus (SLEEP, KINGDOM OF). Andy fancied Nancy, but on the day, when the baby appeared, she was definitely not an Arthur, and not quite a Nancy either. The I’s had it. She was Iris Irena after my grandma and Andy’s Polish grandmother. (‘Irene – according to legend, a widow of Rome who cared for ST SEBASTIAN and nursed him back to health after he had been left for dead, his body full of arrows. She is hence a patron saint of nurses.’) Opening Hall’s where it falls in the small hours with a very small Iris asleep across my lap, I alight on the L’s: Lily, Limbo, Lion, Lizard, Loaves and Fishes, multiplication of, Loincloth, Longinus, Loom . . . Is that not strange and evocative? Does that not conjure a gallery of paintings familiar, once seen and long forgotten? With Hall’s you never know where the winds – see Aeolus, see Boreas, see Flora, see Zephyr – may take you.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 78 © Laura Freeman 2023

About the contributor

Laura Freeman (see Laurel, Apollo, Daphne, Parnassus and Aspergillum) is chief art critic for The Times and author of Ways of Life: Jim Ede and the Kettle’s Yard Artists (2023). You can hear her in Episode 30 of our podcast, ‘Jim Ede’s Way of Life’, talking about art in the 1920s.