One wouldn’t normally associate a book on pipes and pipe-smoking with deceit, guilt and posterior discomfort. This is how it happened.

It was 1964. I was a scholastically challenged 14-year-old from north London who had just undergone double maths. Still dazed, I’d wandered off to the back of the bike sheds where I came across Howard Payne and his cronies furtively dispatching a packet of Gauloises.

Payne was a schoolboy thug with whom I had nothing in common except that it was he who occupied my position at the bottom of the class on those rare occasions when I vacated it. His

favourite trick was to feign largesse by offering a cigarette to the unwary. If you refused, or failed to smoke it without coughing, you would be ridiculed and your shins remodelled.

As I’d never smoked anything before and was rather attached to Nature’s provision in the lower-leg department, I decided to put him off with the following: ‘No thank you, Payne,’ I said. ‘I used to smoke cigarettes when I was young but I now prefer the more mature smoke afforded by a good pipe.’ There followed a torrent of abuse and the fixing of a date after the Easter holidays when I would be required to back up my boast or suffer the aforementioned.

The following morning I was in my local library enquiring about the Government Assisted Passage Scheme to Australia when I happened upon a book written by a tobacconist called Dunhill, a name I’d seen on some of my father’s pipes. The Pipe Book sets out to trace the global history of pipes and pipe-smoking from the sixteenth century to the early decades of the twentieth. Full of easily parrotable facts and insights, comprehensive descriptions of the pipes themselves, photographs and line drawings, it seemed the ideal tool with which to fake expertise and get the better of Payne. I took it home and started reading.

In the 1920s, tobacco consumption in the UK reached its peak and so did Alfred Dunhill’s sales, b

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inOne wouldn’t normally associate a book on pipes and pipe-smoking with deceit, guilt and posterior discomfort. This is how it happened.

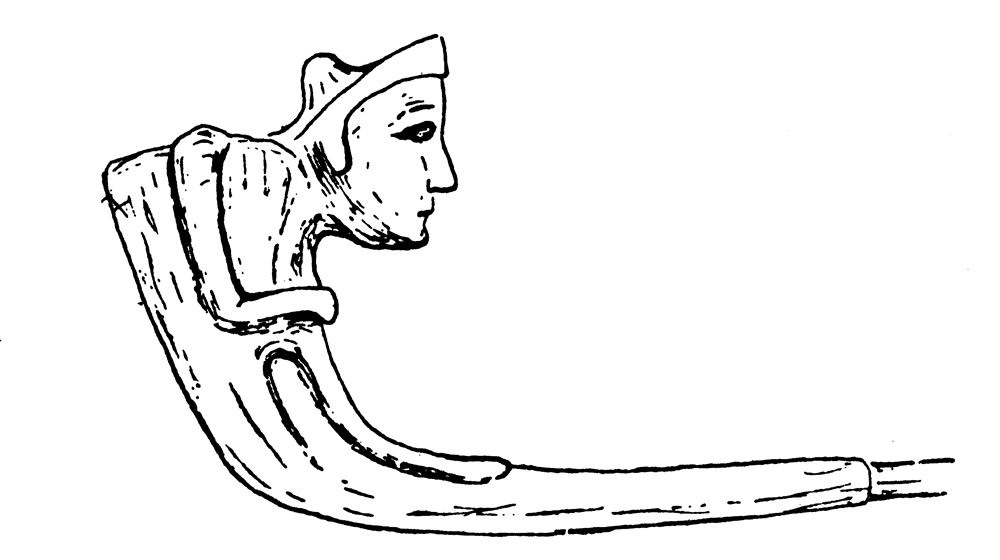

It was 1964. I was a scholastically challenged 14-year-old from north London who had just undergone double maths. Still dazed, I’d wandered off to the back of the bike sheds where I came across Howard Payne and his cronies furtively dispatching a packet of Gauloises. Payne was a schoolboy thug with whom I had nothing in common except that it was he who occupied my position at the bottom of the class on those rare occasions when I vacated it. His favourite trick was to feign largesse by offering a cigarette to the unwary. If you refused, or failed to smoke it without coughing, you would be ridiculed and your shins remodelled. As I’d never smoked anything before and was rather attached to Nature’s provision in the lower-leg department, I decided to put him off with the following: ‘No thank you, Payne,’ I said. ‘I used to smoke cigarettes when I was young but I now prefer the more mature smoke afforded by a good pipe.’ There followed a torrent of abuse and the fixing of a date after the Easter holidays when I would be required to back up my boast or suffer the aforementioned. The following morning I was in my local library enquiring about the Government Assisted Passage Scheme to Australia when I happened upon a book written by a tobacconist called Dunhill, a name I’d seen on some of my father’s pipes. The Pipe Book sets out to trace the global history of pipes and pipe-smoking from the sixteenth century to the early decades of the twentieth. Full of easily parrotable facts and insights, comprehensive descriptions of the pipes themselves, photographs and line drawings, it seemed the ideal tool with which to fake expertise and get the better of Payne. I took it home and started reading. In the 1920s, tobacco consumption in the UK reached its peak and so did Alfred Dunhill’s sales, but he was no ordinary tobacconist. Born in Hornsey, north London, in 1872 and privately educated, at the age of 32 he invented the ingenious ‘windshield pipe’ to assist smokers on bicycles and in open-topped cars. By the time The Pipe Book was published in 1924 he had become a highly regarded collector of pipes, a successful retailer of bespoke tobacco blends and products, and a manufacturer of high-quality pipes bearing his name. He had shops in London, Paris and New York, a royal warrant from Edward, Prince of Wales, and a customer list that included Siegfried Sassoon, Winston Churchill and the actor Basil Rathbone who, incidentally, smoked a Dunhill briar during his first on-screen outing as Sherlock Holmes. An elementary investigation revealed that I had insufficient pocket-money to purchase any pipe, let alone a Dunhill; and as my father’s briars were displayed in constant view on a wooden table-top rotunda next to his armchair, a covert operation to borrow one of his was out of the question. As indeed was purchasing tobacco: since 1908 it had been illegal for anyone under the age of 16 to buy or consume tobacco products. My eye, however, fell on the chapter entitled ‘Makeshift Pipes and Tobacco’, in which Dunhill explains that it was once common for people to assemble an ad-hoc pipe whenever they fancied a smoke. For example, about five hundred years ago the Montbutto tribe from the Congo used the midrib of a plantain leaf ‘bored all through with a stick’ into which they inserted ‘a plantain leaf twisted up into a cornet’. In the absence of tobacco the cornet was filled with dried local flora and ignited. I discovered, too late, that this method had sickening consequences when applied to my parents’ shrubbery and herbaceous border. I asked my father why smoking a pipe didn’t make him feel bilious. He replied that smoke from pipe-tobacco is rarely inhaled into the lungs, but drawn into the mouth where the mucus membranes absorb the chemicals in the smoke and produce the desired effect. As I had no pipe-tobacco to inhale or draw in, a fresh approach was needed, and I put in place a simple three-part plan: 1. Retrieve from tool-shed one of Father’s empty tobacco tins. 2. At night while parents sleep move small quantity of tobacco from Father’s tobacco-pouch to said tin. 3. Return to bed with said tin, leaving Father none the wiser. The sequel was unexpected. I spent a sleepless night racked with guilt while conducting an internal debate on whether ‘Theft Is Always Wrong’. Then, a few minutes before dawn, I arrived at the following conclusion: ‘If thief intends to replace stolen tobacco as soon as he can save sufficient pocket-money and is old enough to do so, then it isn’t stealing but borrowing.’ Ditto Swan Vestas from my father’s desk drawer. Dunhill’s chapter ‘Indian Pipes and Pipe Mysteries’ contained the intriguing information that some native Americans would fashion a smoking device from the earth itself. Various methods were used including ‘building a bowl on the ground from a clod of wet clay, and thrusting into the side of it a long hollow reed to serve as a stem’. When in possession of an actual pipe they regarded it with reverence. ‘It was seen as the instrument by which the breath of man ascended to God through fragrant smoke, carrying with it the prayer or aspiration of the smoker.’ Hence the common use of a pipe to cast spells on an enemy, the smoke wafted in the direction of the Hated One. (This raised a pleasing prospect of Payne’s body parts dropping off.) The Omaha were one of many tribes who used pipes and pipe-smoking to help them in the making of decisions, such as whether the tribe should go to war or maintain the peace. Dunhill has a line-drawing which shows the war-pipe – a surprisingly plain and simple affair with a straight stem about two feet long made of hollowed-out ash-wood, and a simple bowl adorned with just a small totemic shape where it meets the stem. The peace-pipe, however, while similar in size and construction to the war-pipe, was elaborately and colourfully decorated with bird feathers and animal hair, each tuft of hair and barb of feather so steeped in totemic significance that a stranger needed only a quick glance to identify the pipe-owner’s tribe. The other twelve chapters of the book – unread by me in 1964 but read with fascination fifty years later – are either organized by locale, such as ‘Pipes of the Far North’ (bowls carved from stone and walrus bone by the Eskimo, or Inuit), or by type, such as ‘Water Pipes’ (cooling and cleansing the smoke by passing it through water, popular in Africa and Egypt). The book’s final chapter, ‘The Modern Briar’, brings us to the early decades of the twentieth century and the answer to the question: Why is it that so many pipe-smokers choose a pipe made from briar wood? The root of the bruyère bush, indigenous to the whole margin of the western Mediterranean, was discovered during the seventeenth century to be a durable hardwood capable of resisting heat and therefore cool to the hand. That same durability makes it suitable for machining into the standardized shapes used for mass production; and the briar’s tight grain becomes very attractive when buffed and polished. When Dunhill was researching his book, 30 million briar-pipes were manufactured in France every year, 25 million of which were exported to Britain. ‘The twentieth-century connoisseur’, writes Dunhill, ‘selects his pipe for the excellence of its workmanship, the correctness of its proportions and, above all, for the delicate beauty of its flawless, straight-grained bowl.’ Ideal for display on a wooden table-top rotunda. On the first morning of the new school term, I put my tobacco and Swan Vestas into my satchel, ensured my socks were securely gartered, and cycled off to school ready for Payne. A small crowd had gathered, Payne and his cronies at the front smoking something possibly Turkish, and about a dozen first-years behind. I headed straight for the groundsman’s hut and emerged carrying a garden trowel. ‘I shall now demonstrate earth-smoking,’ I announced. ‘It is an ancient technique described by Alfred Dunhill in his authoritative work The Pipe Book and practised by the legendary Red Indians – Crazy Horse, Tonto and Sitting Bull.’ I dropped to my knees and, with the help of the trowel, assembled from the soil a six-inch volcano. Into its top I tipped the tobacco from my tin and, into its side, fashioned an aperture through which tobacco smoke could be drawn. I struck a Swan Vesta and put a flame to the tobacco. I then lay belly down, cupped my hands about the aperture, put my mouth to my hands and, without a single cough, drew in. My first exhalation brought forth an Ooh! from the first-years; the second an Aaah!; at the third they gave a round of enthusiastic applause. Payne, his contorted lips struggling with a half-formed monosyllable, reluctantly stepped forward and patted me on the shoulder. Unfortunately, I had failed to notice a sudden thinning of the crowd and the equally sudden arrival of P. W. Travers (Headmaster) and F. Nobbs (Groundsman). After waiting patiently for my explanations to cease, Travers remarked that he too had read The Pipe Book and was the proud owner of a seventeenth-century Red Indian ‘pipe of peace’. ‘May I suggest’, I said, ‘that you light up immediately and draw in several times before considering any future action.’*

To this day pipe-collectors the world over consider The Pipe Book essential reading. As tobacco sales in Britain waned, the Dunhill company built on its reputation for well-made products, and successfully diversified into the luxury goods market. Alfred Dunhill FRSA died in Worthing, Sussex, in 1959; he was survived by his wife, two sons and the global brand which bears his name.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 68 © Laurence Scott 2020

About the contributor

Laurence Scott lives in a small town in south-west Scotland. His poetry pops up occasionally in magazines and journals, his prose in Slightly Foxed.