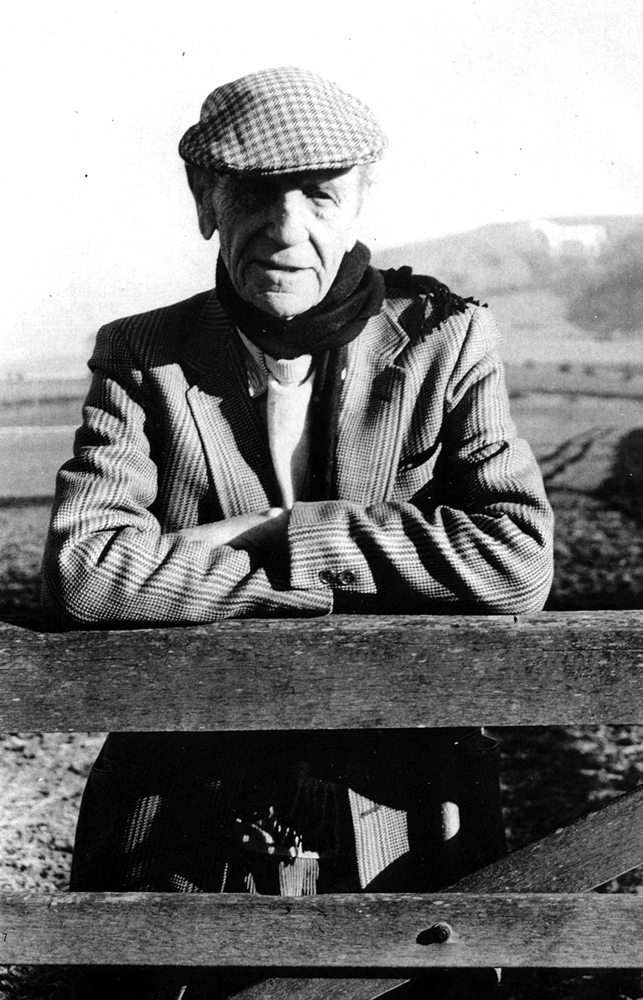

Gone are the days when children could be out of the house from breakfast till suppertime, messing about in boats or dangling over cliffs searching for birds’ eggs, and no one would give them a second thought. Hilary Hook, born in 1917, grew up in Devon in one such benignly neglectful family. In his late sixties he became, to his surprise, a household name, following the screening of Molly Dineen’s 1984 documentary Home from the Hill.

This was the story of Hilary, the old colonial hand, aware of encroaching age in a changing world, who returned to England and exchanged life in an idyllic, if quirkily staffed Kenyan bungalow, bursting at the seams with what he referred to as ‘personal gubbins’, for a small, unstaffed house in Wiltshire. I had remembered that documentary, not least for the moment when the former Great White Hunter was defeated by a can-opener and a tin of ravioli. ‘Damn it,’ he said, ‘I’ll go to the pub.’ So I was delighted to discover that Hilary Hook had written a memoir, its title, like that of the film which preceded it, borrowed from lines by Robert Louis Stevenson:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

Prep school appears to have made little impact on Hilary’s ragamuffin childhood spent sailing, rabbiting, and hunting on a borrowed cob, except, perhaps, for the influence of a kindly headmaster who had been in the Indian Army, and the school’s annual visit to the home of a retired big game hunter. Young Hilary began to dream of India and Africa.

His mother, a genteel widow, thought he’d better go to Oxford and then into the Colonial Service. Hilary saw himself as a game warden in East Africa. The matter was resolved one winter evening when Mrs Hook read aloud to him from a new book sent to her by the subscription library: The Lives of a Bengal Lancer by F. Yeats-Brown. For Hilary there was no longe

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inGone are the days when children could be out of the house from breakfast till suppertime, messing about in boats or dangling over cliffs searching for birds’ eggs, and no one would give them a second thought. Hilary Hook, born in 1917, grew up in Devon in one such benignly neglectful family. In his late sixties he became, to his surprise, a household name, following the screening of Molly Dineen’s 1984 documentary Home from the Hill.

This was the story of Hilary, the old colonial hand, aware of encroaching age in a changing world, who returned to England and exchanged life in an idyllic, if quirkily staffed Kenyan bungalow, bursting at the seams with what he referred to as ‘personal gubbins’, for a small, unstaffed house in Wiltshire. I had remembered that documentary, not least for the moment when the former Great White Hunter was defeated by a can-opener and a tin of ravioli. ‘Damn it,’ he said, ‘I’ll go to the pub.’ So I was delighted to discover that Hilary Hook had written a memoir, its title, like that of the film which preceded it, borrowed from lines by Robert Louis Stevenson:Here he lies where he longed to be; Home is the sailor, home from sea, And the hunter home from the hill.Prep school appears to have made little impact on Hilary’s ragamuffin childhood spent sailing, rabbiting, and hunting on a borrowed cob, except, perhaps, for the influence of a kindly headmaster who had been in the Indian Army, and the school’s annual visit to the home of a retired big game hunter. Young Hilary began to dream of India and Africa. His mother, a genteel widow, thought he’d better go to Oxford and then into the Colonial Service. Hilary saw himself as a game warden in East Africa. The matter was resolved one winter evening when Mrs Hook read aloud to him from a new book sent to her by the subscription library: The Lives of a Bengal Lancer by F. Yeats-Brown. For Hilary there was no longer any doubt. He’d cram for the Sandhurst entrance exams, face the rigours of officer training and join the Indian Army. By the age of 20 he was on his way, shipping out to Allahabad via Karachi. His task, to learn some Urdu and find a place for himself in an Indian regiment. He also learned to play polo and shoot crocodile. It was 1938 and there was a growing threat of war, but the Royal Deccan Horse was still a mounted regiment. Home from the Hill (1987) describes cavalry training in the hills of Baluchistan, with iced beer and luncheon delivered by regimental camel. There were encounters with Afghan caravans heading south, laden with carpets and spices, and there was jackal-hunting with the Peshawar Vale foxhounds. Hilary had a short war. Though his regiment dismounted and learned to drive tanks, their deployment was constantly delayed. In frustration he asked to be sent to Burma to fight with the Chindits and spent Christmas Day 1943 in Port Moresby, New Guinea, playing cricket against eleven ageing Australian quartermasters and storemen. The British, he tells us, won by one run. Back in post-war, pre-partition India we begin to see a change in Hilary. Formerly an enthusiastic hunter of game, big and small, he describes the high tension of a shoot, tracking and pursuing a tiger known to be killing livestock, and then his remorse at the sight of the magnificent animal he has felled with a single shot. In future, he vows, he will shoot only for food or, if pushed, to kill a tiger that has been identified as a man-eater. His childhood dream of being a game warden has resurfaced. He is advised, though, that it is a job that pays peanuts, suitable only for a man of private means, and Hilary has none. Instead he signs on for a stint with the Sudan Defence Force. Several times during my reading of this short memoir I needed to get out my atlas: to follow, for instance, his voyage by wood-fuelled paddle-steamer, up the Nile to Equatorial Sudan. This was a man’s world: long, arduous hikes and manoeuvres, shooting birds for the pot, and drinking sundowners with damned good chaps. The rare females who crop up are the kind who are willing to do the drudgery, shopping in Khartoum for groceries and kitchen equipment. Splendid gals. ‘What on earth is a colander?’ wonders Company Commander Hook, scanning a list of recommended camping supplies. Then, more than halfway through the book, something extraordinary happens. Hilary gets married. He is 34 and army life has enabled him to put a bit by, so nothing notable there. What is astonishing is that the marriage is dealt with in a single paragraph. We are told the name of the Kenyan village where it took place, we know the name of the commanding officer he approached for approval of wedding-leave, but of the wife, nothing. She only reappears, shadowlike in the 1960s, as an ex-wife. Also, presumably, as the mother of his two sons. Marriage apparently made little impact on Hilary’s life. He took his bride to his new posting in Northern Sudan. When on duty, he led camel patrols; off-duty he learned Arabic and played polo. We read of a close encounter with a 12-foot python, but of Mrs Hook not a whisper. Was it a matter of valorous discretion or of self-absorbed cluelessness? Though his blokeish charm was very evident in Molly Dineen’s film, my money is on the latter. Hilary’s life crisscrossed the world with occasional furloughs in England or, preferably, in Scotland or Ireland for good fly-fishing. From Sudan to Hong Kong, then to Aden and eventually back to Sudan to the boring desk duties of a military attaché. ‘Too many parties,’ he remembers, ‘with too little whisky and too much warm soda water.’ In his late forties Hilary quit the army. He’d been offered a job as a game warden at the famous Treetops Hotel in Aberdare National Park, Kenya. His deferred dream was about to come true and in due course he and a friend set up a safari company. The only kind of shooting to be done was with cameras. They ranged across the borders of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, living under canvas and showing guests the birdlife and butterflies as well as the Big Five: elephant, lion, buffalo, leopard and rhino. In the wet seasons, April and November, he would retire to the veranda of his house in Kiserian which, like Isak Dinesen’s African farm, was ‘at the foot of the Ngong hills’. By the early 1980s the safari scene was changing. The Tanzanian and Ugandan border areas were either dangerous or inaccessible and the Kenyan reserves were becoming victims of their own popularity, overrun with zebra-striped minibuses and tourists seeking a 24-hour safari experience. At the annual Shikar Club beano at the Savoy in London, Hilary Hook’s death was announced prematurely. He was in fact alive and well and sleeping off a good dinner at the Muthaiga Club in Nairobi. But his Kenya days were numbered. His rented house was sold and its new owner demanded vacant possession. At the age of 67 Hilary decided to call it quits and return to England. Home was the hunter. I learned many things from his book, some more useful than others. That in the Sudan, back in the day, elephant ivory was effectively a currency, useful for paying the grocer, often a Greek or an Armenian. That a squashed watermelon is an effective way to cool an overheated carburettor should that misfortune befall you far from roadside assistance. And that, though not recommended, it is possible to mount and ride an ostrich. I’m conscious that there was a personal element to my enjoyment of Hilary’s memoir. He evokes, for instance, a taste of one of the most challenging and hostile landscapes: the North-West Frontier. It was a place where, two generations earlier, my grandfather fought in the Malakand Rising. But I sense there is a more universal appeal. Hilary writes of a way of life that has completely disappeared. In his heyday there still existed areas of uncharted territory, with the very real possibility of being cut off from rescue or support. It is something hard for us to imagine in these days of super-connectivity. Self-reliance, and a willingness to make decisions and take responsibility for others, were paramount. In short, he makes our well-appointed and safety conscious lives seem dull. These days even an East African safari is conducted in upholstered comfort. Hilary Hook died in 1990, having enjoyed a late career as an entertaining relic of Empire. He was 72 but looked older, kippered by cigarettes and sun. ‘Long years in bad stations,’ he explained. In his Wiltshire retirement he apparently learned how to use a remote control to navigate Ceefax and check the cricket scores, but I suspect he never did fathom the purpose of a colander.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 78 © Laurie Graham 2023

About the contributor

Laurie Graham is a retired novelist and journalist who, like Hilary Hook, never really put down roots. She laments the fact that genuine adventure has been safety-packaged out of existence. She is now a Brother of the London Charterhouse.