For some years now, ‘Secrets of the Kitchen’ has joined ‘Secrets of the Boudoir’ as a satisfyingly prurient source of surrogate pleasure to readers and viewers with time on their hands – a trend kept alive by the likes of Anthony Bourdain, Jamie Oliver, Gordon Ramsay and Rick Stein. But this is lukewarm voyeurism compared with the spicy titbits served up half a century ago by Ludwig Bemelmans in his kitchen memoir to end them all, Hotel Splendide. George Orwell’s treatment of the same subject remains the best known: both are accounts of adventures that took place predominantly between the wars. Bemelmans, however, had learned the knack of turning adversity into advantage that isn’t really on the syllabus at Eton, and Orwell’s harrowing realism hardly makes for entertaining confessions of the Cook and Tell variety. (Many years ago, incidentally, a friend of mine in Paris was standing behind an American customer at Brentano’s bookshop in the Avenue de l’Opéra and heard the lady ask for a copy of Orwell’s classic restaurant guide, Dining Out in Paris and London.)

Only those readers who were captivated as children by his stories about the irrepressible little French girl Madeline will remember the name of Bemelmans, renowned bon viveur, wit, author and illustrator. He was born in Merano, in the Tyrol, that bit of southern Austria that many Italians still think ought to belong to them, and after a spectacularly unsuccessful school career was apprenticed to his hotelier uncle Hans to learn the business. Here he fared no better and after the most serious in a series of scrapes – shooting a head waiter – he was offered a choice between a spell in a correctional institution and emigration to the New World.

Bemelmans landed in New York in 1914 when he was 16, equipped with a working knowledge of French and English, and with some letters of introduction. One of these was to Mr Otto Brauhaus, manager of the Hotel Splendide, in reality the Ritz Carlton on Central Park South, an institution legendary for organizing banquets of such lavish opulence as had not been seen since the days of the Roman Empire. It also boasted America’s most famous chef, the Burgundian Louis Diat, inventor of vichyssoise soup, whose monumental Gourmet’s Basic French Cookbook is, if you can find it, another invaluable vade-mecum to the vanished world of the great hotels.

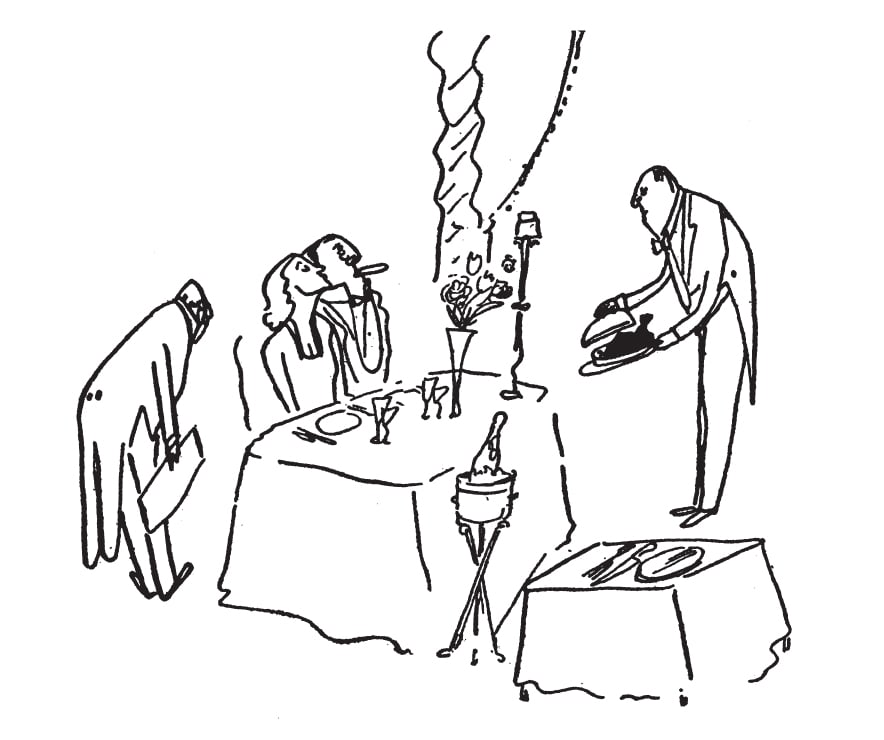

The Ritz Carlton/Splendide was to be Bemelmans’s home for many years, and his book about it, which first appeared in 1956, has now been reissued in a slightly truncated form together with other stories about life under Lucullan tyranny. The new edition is entitled Hotel Bemelmans and is accompanied by scores of the author’s brilliant illustrations which resemble sketches that Edward Lear might have dashed off had he chosen the life of a gay boulevardier. (The bar in the Carlyle Hotel on New York’s Upper East Side still has murals painted by Bemelmans himself, by the way.)

He started work as a lowly commis in the most uncomfortable part of the Splendide’s vast restaurant – a draughty, smelly balcony used by the head waiter Monsieur Victor as ‘a kind of penal colony for guests who had forgotten to tip him over a long period of time and needed a reminder’. Soon, thanks to his native intelligence and ability to learn fast, from all the hundreds of staff employed at the Splendide, Bemelmans came to the attention of the god-like Brauhaus, a kindly character with a thick German accent, known behind his back as ‘Cheeses Greisd’, thanks to his elevated status and his favourite expletive in time of trouble. From the restaurant, the young man moved to the Grill Room and thence to an exalted position in the banqueting department.

This was far and away the most exciting – and complex – part of the Splendide’s operations, catering for small private dinners as well as the kind of parties that Catherine the Great used to throw for Prince Potemkin in the Winter Palace. An elaborate system of partition doors in the banqueting suites created spaces as required, and the intimate suppers were mostly either for what the author calls ‘instantaneous courtship’, or else informal meetings of key players on the financial stage, who after a great dinner would often be inclined to give a good waiter a hot inside tip on the stock market. ‘In this fashion,’ confides Bemelmans, ‘working as an assistant maître d’hôtel in the banquet department, I became rich several times. It was not unusual after a small dinner for one of the waiters to make a thousand dollars.’ His boss, the assistant banqueting manager Mr Sigsag, bought himself a forty-foot motor cruiser from the proceeds.

For men with initiative, the banqueting business was a gold mine, for many of the customers were among the richest people on the planet. And quite apart from tips, which could be astronomical if the guests had enjoyed themselves, there was also commission to be had on all liquor (these were the years of Prohibition, remember), flowers, orchestras and supplies of all kinds.

The scale of pilfering too, especially of fine rare wines, was scarcely credible, thanks to the lavish spending on celebrations such as coming-out dances for society debutantes. Expensive parties on that scale, which lasted until daylight, might involve a staff of up to 300 to look after 2,000 guests, taking over all the hotel’s public rooms for three days: one to set it up, one to add the finishing touches and to have the party, and the third to strike the set, as it were. And still they were pressed for time, as on the occasion when one superannuated dowager decided to build at one end of the ballroom a full-scale replica of her Florida home ‘O Sole Mio’, complete with palm trees, a huge lagoon filled with thousands of gallons of bright blue water, and an authentic gondola imported from Venice.

Running the small dinners was a pushover compared with decadence on that scale, though no less exacting in some ways: when high-flying diners got ‘high’, they could be extremely capricious. As the author sagely observes,

Men important in business or with positions of responsibility in Washington met here, and in the course of an evening a violent change often came on them. They arrived with dignity and they looked important and like the photographs of them published in newspapers, but in the late hours they became Joe or Stewy or Lucius. Sometimes they fell on their faces and sang into the carpet. Leaders of the nation, savants, and unhappy millionaires suffered fits of laughter, babbled nonsense, and spilled ashes and wine down their shirt fronts.

The greatest strength of this nostalgic glimpse into a lost era has to be its cast of colourful grotesques, worthy of some New World Canterbury Tales or Comédie humaine. The author doesn’t like a lot of them and writes with venomous relish of the millionaire plutocrats and their ‘funny little ways’, but he has a lion-tamer’s fond regard for the downtrodden wage-slaves whose lot it was to serve, such as the eccentric Romanian magician Professor Gorylescu and his dog Confetti. The magician never went short of freelance work at private dinners in the hotel, and was well paid for it, but he cherished too costly a passion for the young ballerinas from Anna Pavlova’s troupe, which eventually proved his undoing.

Then there was the magnificently muscular Senegalese with the impressive job description of casserolier, which actually meant manhandling and washing up huge iron pots big enough to boil a hundred chickens. His passion was uniforms, and his prevailing fantasy was to secure a job as doorman at the Splendide. (Eventually Bemelmans took pity on him, dressed him in livery and made him chauffeur of his newly acquired Hispano-Suiza, but since the African had no idea how to drive, he went everywhere in the limousine’s front passenger seat.)

In his reminiscences, Monsieur Louis, as he was professionally known, never descends into sentimentality but writes with lambent clarity and an infectious ebullience of the era of the great hotels in New York. For all-round inspiration and sheer excitement they were the city’s greatest days too, when it was just one helluva town.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 18 © Clive Unger-Hamilton 2008

About the contributor

Clive Unger-Hamilton has been writing and editing books about music for over 30 years. By way of a violon d’Ingres, in 1987 he and his wife opened Hamilton’s Noted Fish and Chips in the rue de Lappe, the first chippie in Paris. He also translates guidebooks for Everyman’s Library.