In the depths of the British Library lies one of the most important collections of wildlife sound recordings in the world. From the common to the endangered, the familiar to the exotic, this treasure trove of animal sounds has captivated listeners for the past forty years. All manner of species are included, from birds and mammals to frogs and even fish. The collective sounds of planet Earth, from quintessentially English woodlands to the steamy rainforests of South America, make up the collection, helping us to learn how animal voices come together to create the soundscapes of our world.

I’m lucky enough to spend my days curating this wonderful archive. Though it was founded in the 1960s, the practice of wildlife sound recording goes back much further than that – in fact to nineteenth-century Germany and a young boy called Ludwig Koch. His father’s gift of an Edison phonograph and a box of blank wax cylinders set Koch on a path that would lead him to become one of the most inspirational figures in sound recording. Determined, patient, innovative and at times bloody-minded, he led the way in overcoming the challenges faced by wildlife sound recordists, and persevered until he achieved what had, until then, been impossible.

Koch’s Memoirs of a Birdman opens in 1889 when, at the age of 8, he made the world’s first ever recording of an animal, and closes in 1953 when he fulfilled a lifelong ambition to visit Iceland and record the mournful calls of the Great Northern Diver. This collection of anecdotes, reflections and regrets opens a window on the past, and allows us a glimpse of the character of this remarkable man.

It’s all too easy now to make a sound recording. You might not be any good at it, but with the advent of handheld recorders, cheap microphones and even smartphones, anyone can have a go. So it’s a real eye-opener to read Koch’s tales of the trials and tribulations of location recording almost a century ago, when th

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn the depths of the British Library lies one of the most important collections of wildlife sound recordings in the world. From the common to the endangered, the familiar to the exotic, this treasure trove of animal sounds has captivated listeners for the past forty years. All manner of species are included, from birds and mammals to frogs and even fish. The collective sounds of planet Earth, from quintessentially English woodlands to the steamy rainforests of South America, make up the collection, helping us to learn how animal voices come together to create the soundscapes of our world.

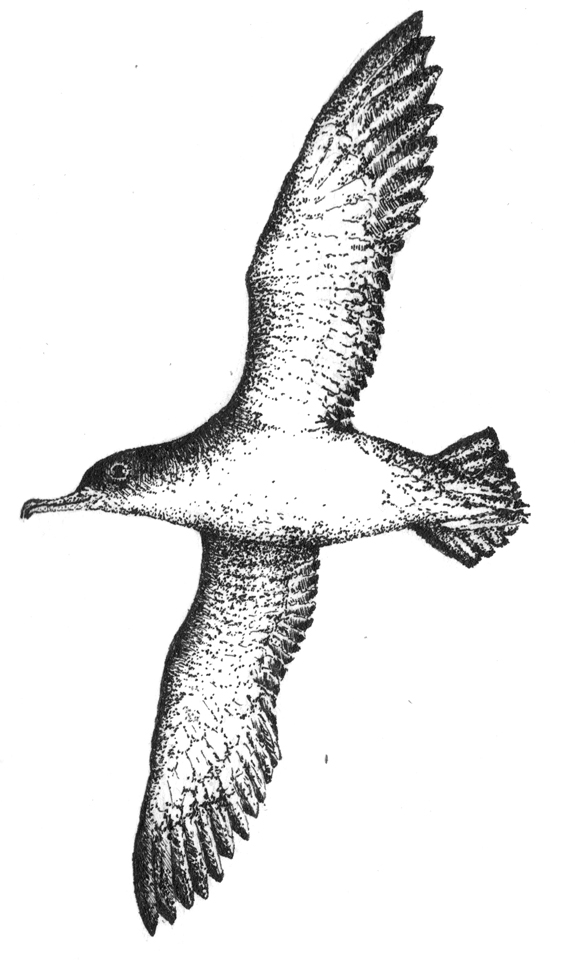

I’m lucky enough to spend my days curating this wonderful archive. Though it was founded in the 1960s, the practice of wildlife sound recording goes back much further than that – in fact to nineteenth-century Germany and a young boy called Ludwig Koch. His father’s gift of an Edison phonograph and a box of blank wax cylinders set Koch on a path that would lead him to become one of the most inspirational figures in sound recording. Determined, patient, innovative and at times bloody-minded, he led the way in overcoming the challenges faced by wildlife sound recordists, and persevered until he achieved what had, until then, been impossible. Koch’s Memoirs of a Birdman opens in 1889 when, at the age of 8, he made the world’s first ever recording of an animal, and closes in 1953 when he fulfilled a lifelong ambition to visit Iceland and record the mournful calls of the Great Northern Diver. This collection of anecdotes, reflections and regrets opens a window on the past, and allows us a glimpse of the character of this remarkable man. It’s all too easy now to make a sound recording. You might not be any good at it, but with the advent of handheld recorders, cheap microphones and even smartphones, anyone can have a go. So it’s a real eye-opener to read Koch’s tales of the trials and tribulations of location recording almost a century ago, when the only options available were wax discs that you couldn’t listen back to while on location and a seven-ton recording van. A combination of unwieldy equipment, miles of cabling between microphone and recorder, a temperamental recording medium and the uncertainty that always comes with working with wild animals, meant that this was not a pursuit for the faint-hearted. Picture the scene: you’ve trudged across miles of country to find the perfect recording spot, you’ve carefully observed your subjects to discover their favourite singing (or calling) post, you’ve climbed up a rickety tree to place your microphone, laid out a mile of cable back to your portable recording van, you’ve heated up your wax discs to the optimum temperature. All is ready. You put on your headphones, your hand hovering over the ‘record’ button, and then . . . nothing. Koch must have had the patience of a saint, because this happened to him time and time again. In 1938, he spent five months at Whipsnade and at London Zoo, recording the calls, cries and bellows of a variety of animals for a new sound-book, Animal Language. Wanting to capture the group howling of Whipsnade’s resident wolves, he placed his microphone near the enclosure and waited. Koch’s collaborator on the project, the evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley, described what happened next:The wolf pack at Whipsnade can only be described as disobliging. As the head keeper explained, the wolves usually start their concerted howling when they hear a particular siren which goes at five each afternoon. But when the microphone was put in position, the siren failed to elicit any response. The wolves looked towards Mr Koch, who was standing by it, with a sort of sly defiance, but remained entirely mute.As a sound recordist myself, I can only sympathize. When you immerse yourself in his memories you can almost hear Koch’s slow, heavily accented voice, familiar to so many radio listeners, rising from the pages. His interest was not restricted to wildlife. From his early experiments with innovative sound devices to the height of his career as an acclaimed field recordist and natural history broadcaster, Koch was fascinated by all things sonic. Before his eventual move to Britain, a position within the German branch of EMI gave him access to the latest recording technology and the opportunity to produce gramophone records on a variety of subjects. His first sound-books appeared in the mid-1920s and featured world music, city soundscapes and, of course, nature. His relationship with the German government, initially forged during the First World War, cemented itself in sound with titles such as Proudly Flies the Flag, while two sound-books released in the 1930s focused on the military, from patriotic songs to rousing speeches. But as the Nazi regime spread its tentacles into every walk of life, Koch found it increasingly difficult to remain in his homeland. Interrogated by the Gestapo and under constant pressure because of his Jewish heritage, he knew it was only a matter of time before the situation became unbearable. Then, while lecturing in Switzerland, he learned that a warrant had been issued for his arrest The time had come to say goodbye. ‘So I landed in Dover on 17 February 1936, and arrived in London,’ he writes in Memoirs of a Birdman, ‘unknown and almost penniless at 5 p.m., welcomed by mist and drizzling rain.’ It was an unpropitious start, yet within a few months he had bagged himself a mobile studio, published the first ever recordings of British birds, played his records to Neville Chamberlain and started a project with the Belgian royal family. In 1941 he joined the BBC, first with the corporation’s European branch and then the Home Service. It was here that his passion for nature recording could be given full rein. He became increasingly involved with the production side of broadcasting, establishing a series of nature programmes that ranged from soundbites dedicated to individual species to more elaborate ‘sound portraits’ that evoked a particular place or time of year. But his real love lay with the great outdoors, and the joy of recording wild animals in their natural habitats. Soon, Koch was back in the field doing what he did best. During his time with the BBC Koch’s passion for wildlife sounds, teamed with his growing archive of animal recordings, saw the birth of a new kind of natural history broadcast. What is today known as the BBC Natural History Unit was beginning to take shape, and Koch was a key figure in its formation. One of the most memorable examples of his work, Music of the Sea, broadcast in 1951, is an audio homage to the many sounds of the sea and the communities, both human and animal, that exist along the coastline of the British Isles. Koch introduced his sound painting with the words: ‘I want you to concentrate for only a quarter of an hour. Close our eyes. Don’t fall asleep. Simply listen.’ Reflecting on this composition and the importance of encouraging his audience to engage fully with sound, Koch explained that the listener ‘was to use his ears in absorbing, say, the beauty of the music of the sea in the same way that a viewer uses his eyes in an art gallery to take in beauty visually’. At the age of 70 Koch travelled to the Scilly Isles to record the ghostly, night-time cries of the Manx Shearwater. Battling the elements and attacks from the birds themselves, he refused to give in.

At a quarter past one I heard through the headphones at last that my discs were recording clearly the fantastic natural symphony of the flight of the shearwaters, a sound which still echoes in my ears, which few have heard, and which no one else has ever succeeded in recording.His sense of pride, satisfaction and awe is still tangible, long after his memories were first committed to paper. A few years after his success with the Manx Shearwater, Koch would fulfil another dream and capture the haunting sounds of the Great Northern Diver. The thing that strikes me most when reading Koch’s autobiography is his unfailing enthusiasm for his craft. He gave himself completely to nature recording, and whenever possible he encouraged his audience, whether on the airwaves or in the lecture theatre, to take the time to stop and listen. He was especially keen to encourage the young: ‘It is our duty to help them to appreciate the beauties of nature and especially the songs of the birds,’ he wrote. Memoirs of a Birdman concludes with the words ‘Here ends the Birdman’s story for the time being.’ For me, though, this book represents much more than just the reflections of a ‘fanatic with a one-track mind’, as he describes himself. It has inspired me to delve deeper, to understand more, and to share my admiration for one of the greatest ambassadors of natural sounds the world has ever seen.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 43 © Cheryl Tipp 2014

About the contributor

Cheryl Tipp is Curator of Natural Sounds at the British Library. Her recent online publications include Listening to Lost Voices (Noch, 2013) and Edward Avis and the Art of Mimicry (Caught by the River, 2013).