I have a childhood memory of being ill in bed, bored and grumpy until my mother came up with an idea of genius. This must have been in late 1953 or 1954 because we had a children’s version of The Ascent of Everest and, like most people at the time, were captivated by the con- quest of the world’s highest mountain. My mother showed me how to position my knees under the eiderdown, roped two miniature naked pink plastic figures together with blue wool and we re-enacted the ascent. Through the Khumbu icefall, up the South Col and the Hillary Step and on to the summit. The magic of those names.

It was a game that kept me entranced for hours and inspired my lifelong interest in the literature of mountaineering, despite a deep-rooted dislike both of heights and of being cold and uncomfortable. Sherpa Tenzing Norgay was my hero, and in all my ascents, he, naked and bright pink, reached the summit first.

And so it began. Over the years I read about Mallory and Irvine, followed Eric Shipton’s exploits in the Himalayas, felt the hair on the back of my neck prickle as I struggled off a Peruvian mountain with Joe Simpson, broken leg and all. But only later did I find a copy of No Picnic on Mount Kenya (1952) by Felice Benuzzi, though I already knew of the book. My parents had both been stationed in Kenya during the Second World War – it was where they met and married – and I remember hearing them reminisce about the stir Benuzzi’s adventure had caused during the war.

Felice Benuzzi was an officer in the Italian Colonial Service in Abyssinia. He was captured by the British in 1941 and ended up in a POW camp in Nanyuki at the foot of Mount Kenya. Benuzzi was an experienced mountaineer, with climbs in the Dolomites and the Alps to his credit, and when he caught a glimpse of the summit of Mount Kenya emerging from its enc

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI have a childhood memory of being ill in bed, bored and grumpy until my mother came up with an idea of genius. This must have been in late 1953 or 1954 because we had a children’s version of The Ascent of Everest and, like most people at the time, were captivated by the con- quest of the world’s highest mountain. My mother showed me how to position my knees under the eiderdown, roped two miniature naked pink plastic figures together with blue wool and we re-enacted the ascent. Through the Khumbu icefall, up the South Col and the Hillary Step and on to the summit. The magic of those names.

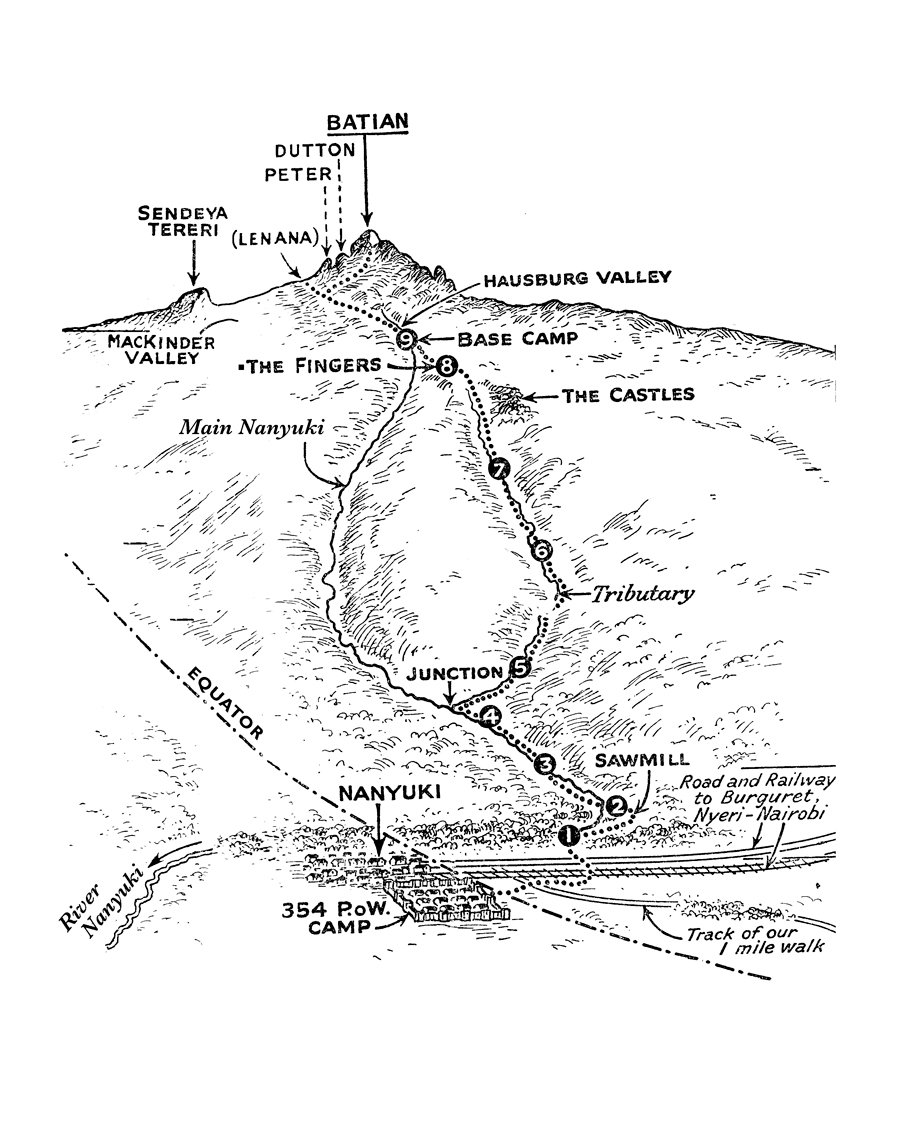

It was a game that kept me entranced for hours and inspired my lifelong interest in the literature of mountaineering, despite a deep-rooted dislike both of heights and of being cold and uncomfortable. Sherpa Tenzing Norgay was my hero, and in all my ascents, he, naked and bright pink, reached the summit first. And so it began. Over the years I read about Mallory and Irvine, followed Eric Shipton’s exploits in the Himalayas, felt the hair on the back of my neck prickle as I struggled off a Peruvian mountain with Joe Simpson, broken leg and all. But only later did I find a copy of No Picnic on Mount Kenya (1952) by Felice Benuzzi, though I already knew of the book. My parents had both been stationed in Kenya during the Second World War – it was where they met and married – and I remember hearing them reminisce about the stir Benuzzi’s adventure had caused during the war. Felice Benuzzi was an officer in the Italian Colonial Service in Abyssinia. He was captured by the British in 1941 and ended up in a POW camp in Nanyuki at the foot of Mount Kenya. Benuzzi was an experienced mountaineer, with climbs in the Dolomites and the Alps to his credit, and when he caught a glimpse of the summit of Mount Kenya emerging from its encircling wreath of cloud, the vegetative state of captivity he describes took on a new dimension. Escape was a possibility – not to attempt the 1,000-mile hike to neutral Portuguese East Africa, but to climb the beautiful, snow-capped peak that sits on the Equator with one face looking towards each hemisphere, and then return to the camp. It would be an adventure, a way to snap the shackles of imprisonment.In order to break the monotony of life one had only to start taking risks again, to try to get out of this Noah’s Ark, which was preserving us from the risks of war but isolating us from the world, to get out into the deluge of life. If there is no means of escaping to a neutral country . . . then, I thought, at least I shall stage a break in this awful travesty of life. I shall try to get out, climb Mount Kenya and return here.Having seen the peak, Benuzzi began his preparations. Finding companions wasn’t easy – some competent climbers thought he was completely insane. But eventually he assembled a team of three – himself, Giuàn Balletto who was a doctor and fellow climber, and Enzo Bassotti, not a mountaineer but needed as a third man to stay at base camp while the other two made the final assault on the peak. Equipment, including home-made crampons and ice-axes, warm clothes and food, was ‘liberated’, bartered for, made or otherwise acquired and plans were set in motion. Benuzzi and his companions rejected the idea of bribing the guards to make their escape: they considered that to be ‘low’. This is one instance of the faint flavour of Boy’s Own adventuring that surrounds the whole escapade. However, it is underpinned throughout by a more spiritual, thoughtful atmosphere. It is this juxtaposition that gives Benuzzi’s book so much of its appeal. Adventure sure enough, but with a more profound soul. Once out of the camp, via the vegetable garden where they were allowed to work, the escapees had to get through an inhabited area, walking at night. After that the danger was nature itself. Mount Kenya is home to big and dangerous animals – elephant, rhino, leopard and the like. Benuzzi and his companions had seen a small-scale map taken from a book, and they had a profile of the mountain from the side they couldn’t see, the trademark label from a tin of Kenylon Meat and Vegetable Rations, a brand made by Oxo. It was not a well- equipped expedition by any means, but what mattered to the trio was the sense of being in control of their own destiny.

As knights of old crossed perilous seas, fought fiery dragons and even each other, for the love of their princesses, so nowadays mountaineers armed with ice-axes and ropes, crampons and pitons, make dangerous and wearisome journeys and endure every hardship for the sake of their mountains. And in winning their beloved, many of them lose their lives.No lives were lost on this expedition, but they came pretty close. Following the glacial streams up the mountain, they passed through forests of bamboo and giant heather. Benuzzi manages to create a sense of wonder rather than a litany of hard slog, though make no mistake, hard slog it was:

Every step led to new discoveries, and we were continually in a state of amazed admiration and gratitude. It was as though we were living at the beginning of time, before men had begun to give names to things.Bassotti, unwell at the start, suffered from the altitude – Mount Kenya rises to over 17,000 feet – and everything took longer than anticipated, with dire implications for their food supplies. But they finally managed to establish a base camp for their attempt on the summit. Faced with an unknown route and icy blizzards, Benuzzi and Balletto failed in their attempt to summit the Batian peak, the highest point on the mountain. But despite the fact that their food was almost exhausted, they decided to have a go at the lower Lenana point. It was here that they would place their home-made Italian flag, proof of what they had achieved, later to be retrieved and acknowledged, somewhat grudgingly, by the British.

If anyone wonders what it meant to us to see the flag of our country flying free in the sky after not having seen it so for two long years, and having seen for some time previous to this only white flags, masses of them, I can only say that it was a grand sight indeed.When climbing Lenana, the two had spotted a hut that pointed to what they correctly guessed was the established route to the summit. They were tempted to explore the hut, for it might contain some desperately needed food, and have one last shot at Batian. But they would have had no way of leaving money for the food – if there was any – and they felt that to use a British hut and steal its contents would be ‘unsporting’. The standards of a bygone era. The story of the descent is as much of an epic as the ascent. The three struggled on, getting nearer to food, but also to captivity after seventeen days of liberty. Once back, they were sentenced to twenty- eight days in the cells, though the commandant let them out after seven, in recognition of their sporting effort. But in what seems to me a very mean move the British then moved them to another POW camp, one for hard cases, where they would have no view of their mountain, and, presumably, no temptation to escape. They were to endure three more long years of captivity. Felice Benuzzi wrote No Picnic on Mount Kenya twice, once in Italian and once in English, not using a translator in the usual way. When the war was over he was reunited with his family and went on to have a distinguished career as a diplomat. He died in 1988. The home-made kit from the expedition was eventually rescued from where they had left it on Mount Kenya and is now in the mountain- eering museum in Chamonix. The flag they raised on Point Lenana was returned to Benuzzi, who donated it to the museum in Turin, and a spot on the mountain was named Benuzzi Col in honour of their adventure. But the best memorial to Benuzzi and his companions is the power of their story of mountaineering adventure and what it says about human resilience.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 70 © Margaret von Klemperer 2021

About the contributor

Maragert von Klemperer grew up in the UK but has lived and worked as an arts journalist in South Africa for many years. Now retired, she loves walking among mountains, but not climbing them.