In my school holidays, over fifty years ago, I used to cycle from our family home into Guildford to visit the second-hand bookshops. At the top of the High Street was the vast and wonderful emporium of Thomas Thorp, where the heavily laden bookshelves looked as though they might topple over in a cloud of dust at any minute. In Quarry Street, by contrast, was the magisterial bookshop of Charles Traylen who was described in his obituary in The Times as ‘the last of a breed of grandees of the antiquarian book trade’. Situated in Castle House it was a place in which to browse and to dream, and it was here that I spent much of my time.

Our home was in the village of Worplesdon. It stood in an ancient garden where, as a member of the Home Guard, my father had performed lookout duty during the war from a crow’s nest built high up in an oak tree and from which he could see for miles around. The owners at that time were three spinster sisters, each of them called Miss Thompson. My father bought the house from them in 1947. They were cousins of P. G. Wodehouse and he used to stay there with them before the war. No doubt this accounts for the character known as Lord Worplesdon who, it will be recalled, was the husband of Aunt Agatha and once chased a young Bertie Wooster ‘a mile across difficult terrain with a hunting crop’ for smoking one of his special cigars.

The Thompsons had performed their patriotic duty during the war by growing vegetables in the garden and my parents now set about restoring it to its former glory. One of its main features was a pair of herbaceous borders separated by a lawn some six feet wide that was covered in white frost on cold mornings. It intrigued me that spiders were able during the night to spin their silky aerial skeins across the lawn from the delphiniums on one side to the phlox and hollyhocks on the other – a minimum distance of eight feet ‒ without any intermediate support. It was probably this glimpse

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn my school holidays, over fifty years ago, I used to cycle from our family home into Guildford to visit the second-hand bookshops. At the top of the High Street was the vast and wonderful emporium of Thomas Thorp, where the heavily laden bookshelves looked as though they might topple over in a cloud of dust at any minute. In Quarry Street, by contrast, was the magisterial bookshop of Charles Traylen who was described in his obituary in The Times as ‘the last of a breed of grandees of the antiquarian book trade’. Situated in Castle House it was a place in which to browse and to dream, and it was here that I spent much of my time.

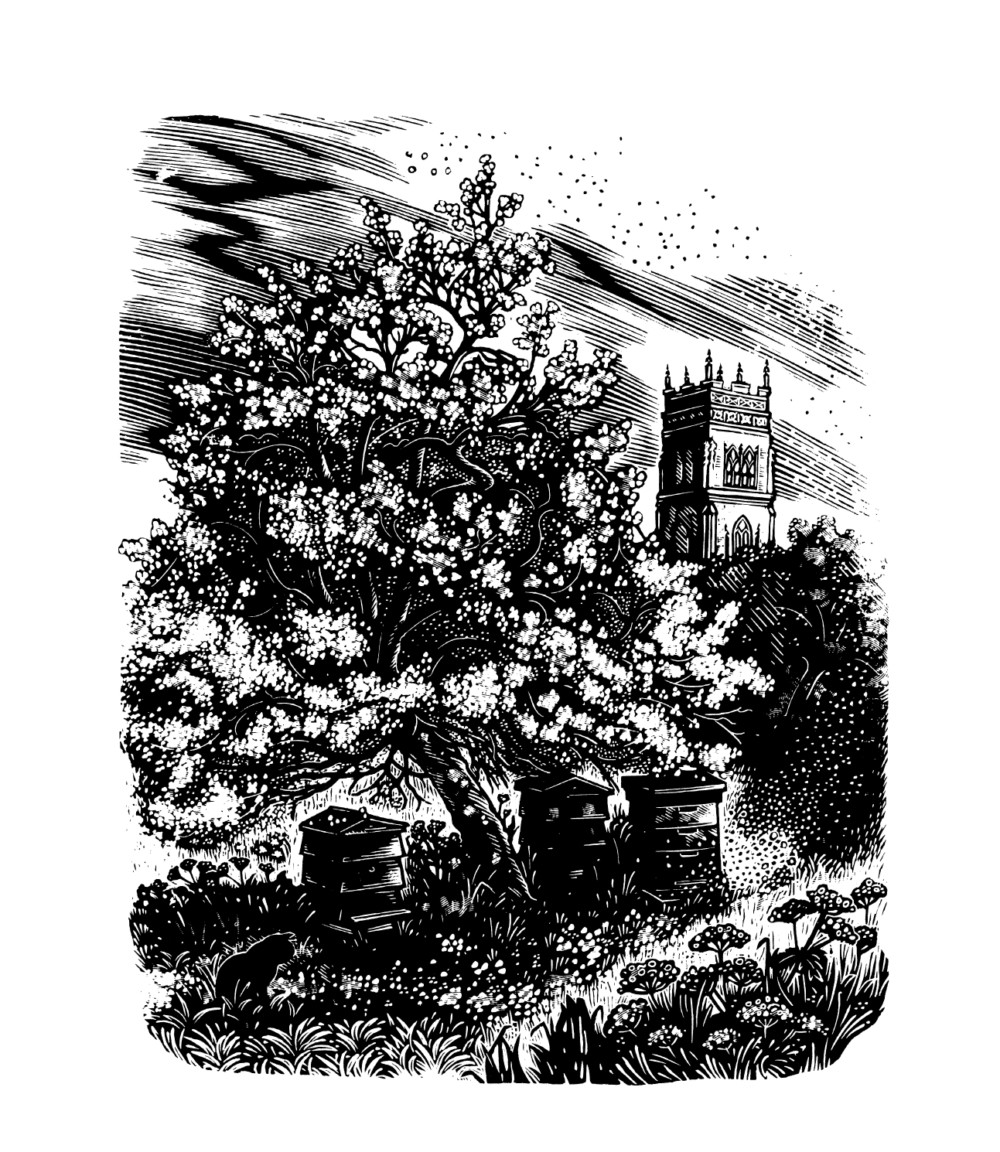

Our home was in the village of Worplesdon. It stood in an ancient garden where, as a member of the Home Guard, my father had performed lookout duty during the war from a crow’s nest built high up in an oak tree and from which he could see for miles around. The owners at that time were three spinster sisters, each of them called Miss Thompson. My father bought the house from them in 1947. They were cousins of P. G. Wodehouse and he used to stay there with them before the war. No doubt this accounts for the character known as Lord Worplesdon who, it will be recalled, was the husband of Aunt Agatha and once chased a young Bertie Wooster ‘a mile across difficult terrain with a hunting crop’ for smoking one of his special cigars. The Thompsons had performed their patriotic duty during the war by growing vegetables in the garden and my parents now set about restoring it to its former glory. One of its main features was a pair of herbaceous borders separated by a lawn some six feet wide that was covered in white frost on cold mornings. It intrigued me that spiders were able during the night to spin their silky aerial skeins across the lawn from the delphiniums on one side to the phlox and hollyhocks on the other – a minimum distance of eight feet ‒ without any intermediate support. It was probably this glimpse into the world of these miniature scaffolders that caused me on one of my visits to Traylen’s bookshop to fasten on a copy of Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Life of the Bee, translated from the French by Alfred Sutro and published by George Allen in 1901. I snapped it up for ten shillings, took it home on my bike, began to read and was transported. Bees have fascinated mankind since earliest times, as evidenced by rock paintings across Africa and elsewhere. The bibliography of bees goes back a long way too and Maeterlinck provides a brief survey from Aristotle and Pliny down to his own day. Real scientific study began in the seventeenth century with the discoveries of the Dutch savant Jan Swammerdam who dissected bees under a microscope and finally settled the sex of the queen, ‘hitherto looked upon as a king’; and by the end of the nineteenth century great strides had been made in the practice of beekeeping by the invention of movable and artificial wax combs and the honey extractor. However The Life of the Bee is not a scientific study or a treatise on practical beekeeping but a study of the bees and their culture written by a man who had observed them during twenty years of beekeeping. ‘The reader of this book’, he says, ‘will not gather therefrom how to manage a hive; but he will know more or less all that can with any certainty be known of the curious, profound and intimate side of its inhabitants’; and he writes ‘as one speaks of a subject one knows and loves to those who know it not’. Each episode in the life of the hive is described, including the laws, the habits, the peculiarities and the events that produce and accompany it: the formation and departure of the swarm; the foundation of the new hive; the birth, combat and nuptial flight of the young queens; the massacre of the males; and the return of the sleep of winter. Maeterlinck is not content to rest there. What he sets out to do is explain why they behave as they do: that is, with extravagant care for the hive and each other on the one hand and yet with savage cruelty and recklessness on the other. He seeks to identify a unifying principle that explains why, for example, they offer the queen loving care and protection while she is laying her eggs but then cynically abandon her when she has ceased to be fertile; or why they tolerate the presence in the hive of several hundred males – those ‘foolish, clumsy, useless, noisy creatures, who are pretentious, gluttonous, dirty, coarse, totally and scandalously idle, insatiable, and enormous’ – only one of whom will be chosen to impregnate the new queen, and then, at the appropriate time, ‘coldly decree the simultaneous and general massacre’ of every one of them. Fundamental to their behaviour is what he calls ‘the essential trait in the nature of the bee’: namely, that it is a creature of the crowd. When the bee leaves the hive to go foraging it behoves it, under pain of death, to return at regular intervals ‘and breathe the crowd as the swimmer must return and breathe the air’. If it does not, and however abundant the food or favourable the temperature, it will die within a few days. From the hive it derives an ‘invisible aliment’ that is as necessary to it as honey. This craving, he says, helps to explain ‘the almost perfect but pitiless society’ of the hive where ‘the individual is entirely merged in the republic’ and the republic in turn is invariably sacrificed ‘to the abstract and immortal city of the future’. This spirit of the hive explains all the behaviour of bees, he concludes, including the allocation of work among them. It allots their respective tasks tothe nurses who tend the nymphs and the larvae, the ladies of honour who wait on the queen, and never allow her out of their sight; the house-bees who air, refresh or heat the hive by fanning their wings, and hasten the evaporation of the honey that may be too highly charged with water; the architects, masons, waxworkers and sculptors who form the chain and construct the combs; the foragers who sally forth to the flowers in search of the nectar that turns into honey, of the pollen that feeds the nymphs and the larvae, the propolis that welds and strengthens the buildings of the city, or the water and salt required by the youth of the nation.Skilfully, almost as if telling a story, Maeterlinck unravels the secrets of the hive and transmits his fascination and curiosity to the reader. Each chapter is broken down into short sections and this reduces a complex subject to simplicity and clarity. It is not merely a pleasure to read; in places it is gripping. He was, of course, a skilled writer and in 1911 was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature ‘in appreciation of his many-sided literary activities’. It is not surprising, therefore, that he is able to rise to the occasion. His description of the nuptial flight, for example, is almost as breathtaking for the reader as for the virgin queen and her tragic consort:

She rises still. A region must be found unhaunted by birds, that else might profane the mystery. She rises still; and already the ill-assorted troop below are dwindling and falling asunder. The feeble, infirm, the aged, unwelcome, ill fed, who have flown from inactive or impoverished cities – these renounce the pursuit and disappear in the void. Only a small, indefatigable cluster remain, suspended in infinite opal. She summons her wings for one final effort; and now the chosen of incomprehensible forces has reached her, has seized her, and, bounding aloft with united impetus, the ascending spiral of their intertwined flight whirls for one second in the hostile madness of love.Maeterlinck carried out numerous experiments with bees and made notes of his observations. He is credited by modern science with being the first to discover that bees communicate with one another. Scientists have now shown how they communicate, namely by a series of dance steps. He also suggested that the survival of the human race might depend on the survival of the bees, and scientists have now endorsed this view. Anyone wishing to read more deeply into the subject can do so by referring to such works as M. L. Winston’s Biology of the Bee (1987); but for the ordinary reader The Life of the Bee provides a perfect introduction. It is a little gem.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 56 © Nicholas Asprey 2017

About the contributor

Nicholas Asprey has now retired after 45 years in practice at the Chancery Bar and has taken up writing articles on subjects of interest to him. He is a Governing Bencher of the Inner Temple and a member of the Library Committee and has served as Editor of the Inner Temple Yearbook.