The first stories I can remember reading in my early childhood were, it seems, mainly about rabbits. But it was the illustrations rather than the words in Beatrix Potter’s and Alison Uttley’s books that I remember most vividly. After this there is a gap in my memory, though I suspect that Enid Blyton’s prolific volumes filled much of that period. It was not until my mid-teens that I entered the exciting and adventurous worlds of Rider Haggard and Conan Doyle (not Sherlock Holmes but Brigadier Gerard was my comic hero).

Much later, after I began writing biographies, I came across several children’s writers I now admire. While working on a life of the artist Augustus John, I discovered that Kathleen Hale, the creator of Orlando the Marmalade Cat, had worked as his secretary in the early 1920s. ‘I felt a frisson whenever he came into the building,’ she wrote. The work of dealing with unpaid bills and unanswered letters was enlivened at times by what she called ‘lots of silly fun’. Out of curiosity, ‘I allowed him to seduce me,’ she added. ‘The sex barrier down, this aberration only added a certain warmth to our friendship.’ I felt something of this warmth and humour when I eventually came to read about her cat with the gooseberry eyes.

One of the significant characters in my biography of Bernard Shaw was Mrs Edith Bland. She appears on my pages as an advanced woman who abstained from corsets, rolled her own cigarettes and called spectacularly for glasses of water at moments of drama at the Fabian Society. This ‘most attractive and vivacious member of the Fabians’ fell in love with Shaw and would accompany him on marathon walks across London which she hoped would end up in his lodgings and which he was determined would lead them to the British Museum. I found myself liking her so much that I began reading her books – the books for children written under her maiden name, Edith Nesbit. According to Julia Briggs’s biography, her publisher was uncertain as to whether her books with their mixture of magic and social comedy were actually for children or aimed at parents who could read them aloud to their children. My belief is that they are perfect for those who, like me, are in their second childhood.

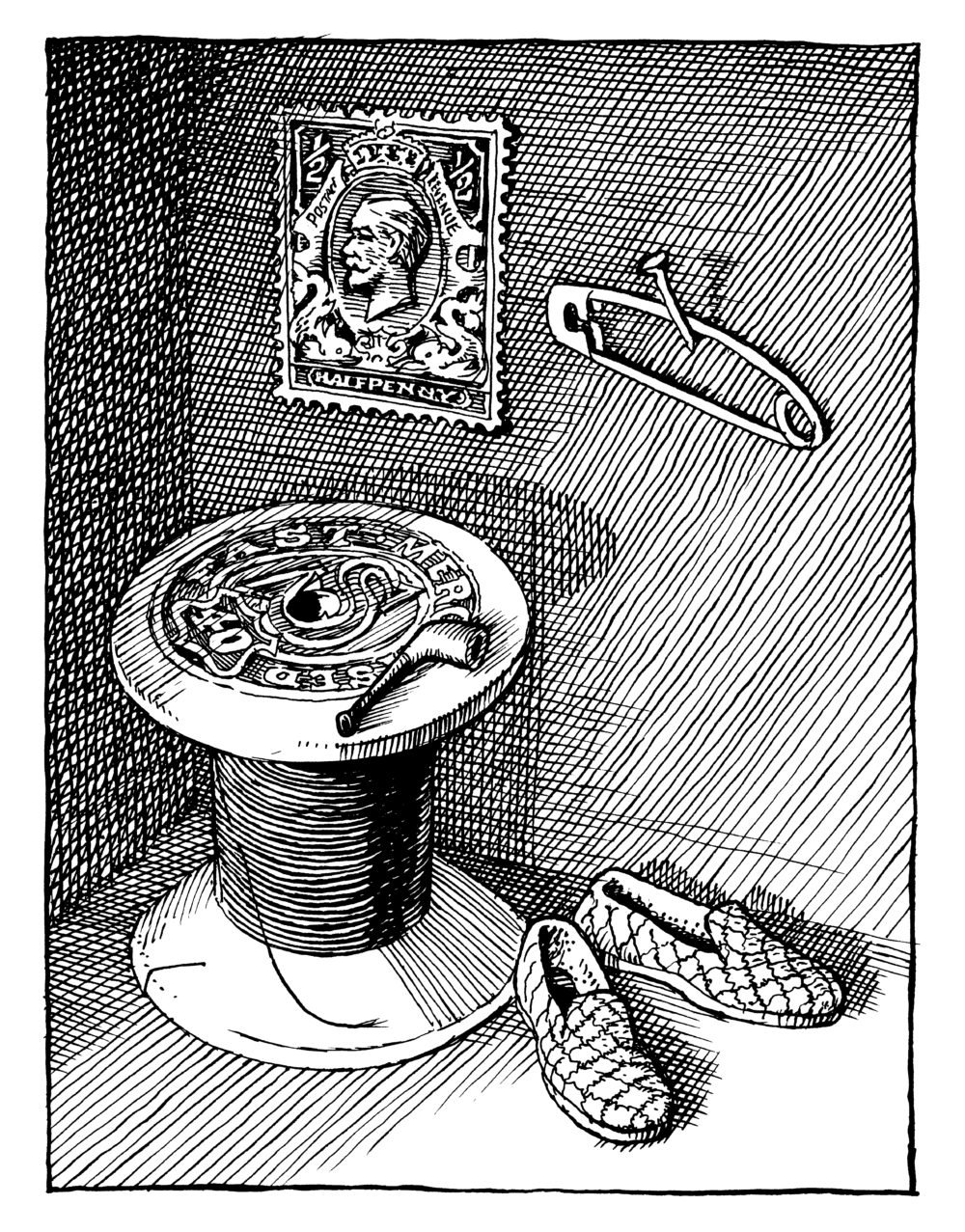

In my late seventies I have finally found for myself – that is without the aid of my biographical subjects – a children’s writer whose satire on adult behaviour is subtly developed and perfectly suited to readers of all ages. This is Mary Norton, whose quintet of novels about the Borrowers was written for the most part during the 1950s. These tiny people, who mimic what they sometimes call ‘Human Beans’, like to think of us giants as having been put on earth to manufacture useful small objects for them. There are, for example, safety-pins (which become coat-hangers), cotton reels (on which to sit), stamps (which are placed as wonderful portraits and landscapes on their walls), toothbrushes (parts of which make excellent hairbrushes) and thimbles (from which they drink tea). All of these items and many more are borrowed or, as the giants would call it, ‘stolen’.

We never see the Borrowers (or only very occasionally after drinking several glasses of Fine Madeira). But we are aware of the number of objects that vanish all the time. Something is always missing and it is this disappearance which, despite their near-invisibility, proves the existence of these Borrowers. It’s elementary, my dear reader. As Sherlock Holmes explained: ‘When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.’

These improbable beings have something in common with the inhabitants of the Island of Lilliput, where Gulliver was shipwrecked in the first part of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (Mary Norton brings in the word ‘shipwreck’ to alert us to this connection). The Lilliputians were some six inches high (slightly taller, I calculate, than the Borrowers), and by recording their wars and social customs on such a diminished scale, Swift’s satire made devastating ridicule of them – which is to say of us. (Another children’s book, T. H. White’s Mistress Masham’s Repose, ingeniously imagines the further fate of Swift’s Lilliputians.)

The three characters in Mary Norton’s first book, The Borrowers, represent a recognizable human family. The head of the family is Pod, a most talented borrower, able when young to ‘walk the length of a laid dinner-table after the gong was rung, taking a nut or sweet from every dish, and down by a fold of the table-cloth as the first people came in at the door’. His wife Homily is an ingenious cook, very house-proud – but fearful of the world outside. Their daughter Arrietty, in her early ’teens, fears nothing – not even cats. She longs to explore ‘the great out-doors’, to bask in the sunlight, to run through the grass, swing on twigs like the birds: in short, to be free from the gloominess of her secret life under the floors and behind the wainscots of Firbank Hall, the great Georgian house where she lives with her parents. It is a hidden, safe existence, like the lives of humans in towns and cities during the Second World War.

In ‘the golden age’, when this mansion was full of wealthy people and there was much to borrow, many little people lived there: the Rain-Barrels, the Linen-Presses and the Boot-Racks, the Brown Cupboard Boys, the rather superior Harpsichords and the Hon. John Studdingtons (who lived behind a portrait of John Studdington). Pod himself belonged to the Clock family, though Homily’s mother was a mere Bell-Pull – which was why she was never invited to the Overmantels’ parties. These aristocratic Overmantels were a stuck-up lot who lived in the wall high up behind the mantelpiece in the morning-room where the Human Beans ate their first meal of the day. The Overmantel women were conceited tweedy creatures who admired themselves in bits of the overmantel mirror; the men were serious whisky drinkers and tobacco smokers. They lived on an eternal breakfast: ‘toast and egg and snips of mushroom; sometimes sausage and crispy bacon with sips of tea and coffee’.

By the time The Borrowers begins, there is only one rich person and a couple of servants left in the house; and only the single Clock family of three small people. It follows that there is less to borrow, but also less chance of being seen. Nevertheless Arrietty has been seen by a 9-year-old boy and, to her parents’ horror, makes friends with him. He brings the Clocks all sorts of terrific furniture from an old dolls’ house in the attic; in payment for this Arrietty reads to him as he lies on his back in the garden, she standing on his shoulder, speaking into his ear and telling him when to turn the page. She improves his reading and at the same time educates herself, learning much about the mysterious world in which they all exist. But this coming together between giants and little people breaks the first rule of the Borrowers. There are good and bad people, artful and honest giants but, as Pod explains to Arrietty, they cannot be trusted: ‘Steer clear of them – that’s what I’ve always been told. No matter what they promise you. No good never really came to no one from any human being.’

And so it proves. The boy’s friendship accidentally leads to the Borrowers being seen by other humans who bring in a cat, a policeman and a rat-catcher carrying his vast equipment of poisons, snares and bellows with lethal gas – in addition to some terriers and a ferret. In the chaos, Pod, Homily and Arrietty escape to the great outdoors, its beauty and its danger, where they have many adventures Afield, Afloat and Aloft. Wherever they go, the same rules about humans apply. Though some are friendly, others seem frightened by such tiny travesties of themselves and wish to eliminate them, while a few try to capture them in order to make money. Such is the human condition. There is a reference in these adventures to Henry Fielding’s mock-heroic farce Tom Thumb, who was sadly eaten by a cow, a Tragedy of Tragedies that brought tears of rare laughter to Jonathan Swift.

What reignites the ingenuity and humour of these volumes is the creation of a supreme Borrower of Borrowers, the amazing Spiller. He doesn’t know how old he is and has no memory of his family beyond his mother telling him at breakfast: ‘A dreadful spiller, that’s what you are, aren’t you?’ So Dreadful Spiller he remains: an outdoors borrower who, with his earth-dark face and bright black eyes, is a master of concealment, melting into the background, disappearing fast and becoming invisible. He is a miraculous hunter. He owns a couple of boats – an old wooden knife-box which he cleverly guides along the river for long journeys carrying strange borrowed cargoes, and the bottom half of an aluminium soap-case, slightly dented, for more modest expeditions. He is fearless, but suddenly shy when saving the lives of the Clock family. His teasing smile greatly attracts Arrietty, for whom he embodies the whole wide out-of-doors world.

Spiller leads the Clocks to Homily’s brother’s family, which enables Mary Norton to balance self-reliance against family life (so many people, so many rules, so much for show and so little for use). ‘Poor Spiller,’ thinks Arrietty. ‘Solitary they called him . . . Perhaps that’s what’s the matter with me.’ Mary Norton is not sentimental about families. She seems to prefer the individual enterprise of Spiller and Arrietty who are both loners.

Four of Mary Norton’s Borrowers’ books were published within nine years. Then, after an interval of twenty-one years (and ten years before her death), she brought out her final volume, The Borrowers Avenged, in 1982. It begins where The Borrowers Aloft ended – as if no time has passed. Having made a complicated escape from an attic prison by balloon (an achievement overlooked by Richard Holmes in his book of balloons, Falling Upwards), the Clocks are led by Spiller on an adventurous journey to an ancient, overgrown rectory. Here, amid danger, excitement and surprise, they encounter new and old friends and enemies. One question remains: what will be the future for Arrietty? Will it be with Spiller, the borrower who belongs to the outdoors, or Peagreen, an attractive young borrower with a charming smile, who was abandoned by the Overmantels and belongs to the indoor life? Perhaps this could be decided through a new literary prize written in competition by admiring borrowers of Mary Norton’s characters.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 42 © Michael Holroyd 2014

About the contributor

Michael Holroyd has written the Lives of Bernard Shaw, Augustus John, Lytton Strachey and himself. He is half Swedish and partly Irish – which may account for some of his literary judgements (Mary Norton spent her last years in Ireland).