In January 1954, a vignette appeared in the New Yorker’s ‘Talk of the Town’ section, introduced only vaguely as a missive from ‘a rather long-winded lady’. The piece – like all ‘Talk’ stories then, unsigned – was a lightly sardonic first-person account of a woman’s disastrous experience in a dress shop. It might not have been world-changing, but it did stand out from the usual ‘Talk’ pieces, which were often impersonal, mannered little things, written in the royal ‘we’. The Long-Winded Lady, though, idiosyncratic from the beginning, spoke only for herself. ‘Well, there you are,’ she signed off, ‘in case you’ve paid any attention.’

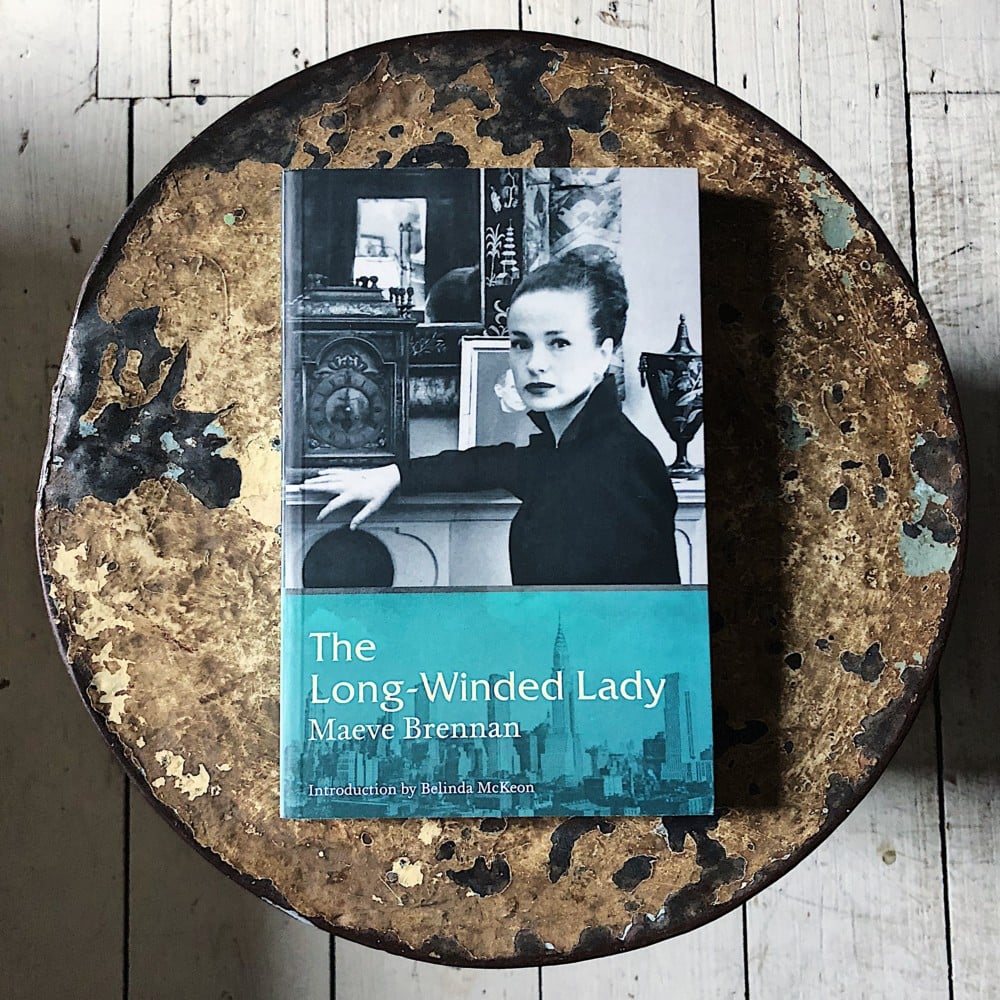

Such pieces, ostensibly slight essays on life in Manhattan, continued to appear, on and off, until 1981. They were always unsigned, and introduced only with a phrase like ‘Our friend the long-winded lady has written to us as follows’, but when in 1969 a collection was assembled for publication, the writer’s identity was revealed. She was, it turned out, Maeve Brennan, an Irish author of short stories and a New Yorker staff writer.

This revelation was a shame, I reckon. It’s hard now to take these odd little pieces – quasi-anonymous, after all – in the manner in which they were intended. Brennan’s life – which in tabloid-headline form runs something like ‘ultra-elegant model for Holly Golightly ends up mad bag lady’ – casts a long shadow over her work, particularly this side of the Atlantic, where none of her books was published in her lifetime. It’s arguable, in fact, that the subsequent biography of her, as much as the work itself, was responsible for the mini-revival she underwent at the turn of the millennium. You can see why. ‘Mad, destitute writer’ makes good copy. Add to that the Breakfast at Tiffany’s glamour, and the tragic-downfall articles write themselves.

I was lucky to come across the essays when I was too young to know about the New Yorker, never mind Maeve Brennan. To me, they were just prose snapshots of city life taken by an archetype with which – having been raised in a busy city myself – I was familiar: the quietly eccentric urban solitary. And that first impression lingers. I see her in every city I visit.

In the earliest pieces, the Long-Winded Lady is a two-dimensional comedic persona, that of a well-heeled suburbanite shopping her way around the nicer parts of Manhattan. But as the essays keep coming, the character deepens. A noticeable change occurs in 1960, when Brennan, aged 43, goes through a divorce and, after time spent away, returns to the city alone. The humour turns brittle, and melancholy, hitherto repressed, starts to predominate. The Long-Winded Lady from this point comes very close indeed to reflecting her writer’s character and its vicissitudes.

Keeping to her parts of Manhattan – Midtown and Greenwich Village mainly – the Long-Winded Lady eavesdrops on ‘the most cumbersome, most reckless, most ambitious, most confused, most comical, the saddest and coldest and most human of cities’, as Brennan calls it in her note to the 1969 collection. Sometimes she watches the world from her window or, if her current room has one (she moves a lot), her balcony. Mostly she’s out, though, ambling through the most vital, open streets in the world. She hears that a wooden farmhouse is being transported from Uptown to Greenwich Village and goes to see it (‘Charles Street is a nice street, a good place for a house to move to’). She visits the local haberdashery to inspect the damage from a fire whose smoke she saw the night before. She watches a parade, or a protest. She shops for shoes or books or, once, ‘one of those plain glass orange squeezers’. Her favourite activity, though, is watching the goings-on in ‘small, inexpensive restaurants’, which she believes are ‘the home fires of New York City’.

‘It is not the strange or exotic ways of people that interest her,’ Brennan writes in the same note, ‘but the ordinary ways, when something that is familiar to her shows.’ Her style is built upon this ordinariness, and it’s one of the reasons she was referred to – when referred to at all – as Chekhovian. Her metaphors, like his, manage to be both rich and remarkably close to their occasion: a man enters a restaurant with a bundle

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn January 1954, a vignette appeared in the New Yorker’s ‘Talk of the Town’ section, introduced only vaguely as a missive from ‘a rather long-winded lady’. The piece – like all ‘Talk’ stories then, unsigned – was a lightly sardonic first-person account of a woman’s disastrous experience in a dress shop. It might not have been world-changing, but it did stand out from the usual ‘Talk’ pieces, which were often impersonal, mannered little things, written in the royal ‘we’. The Long-Winded Lady, though, idiosyncratic from the beginning, spoke only for herself. ‘Well, there you are,’ she signed off, ‘in case you’ve paid any attention.’

Such pieces, ostensibly slight essays on life in Manhattan, continued to appear, on and off, until 1981. They were always unsigned, and introduced only with a phrase like ‘Our friend the long-winded lady has written to us as follows’, but when in 1969 a collection was assembled for publication, the writer’s identity was revealed. She was, it turned out, Maeve Brennan, an Irish author of short stories and a New Yorker staff writer.

This revelation was a shame, I reckon. It’s hard now to take these odd little pieces – quasi-anonymous, after all – in the manner in which they were intended. Brennan’s life – which in tabloid-headline form runs something like ‘ultra-elegant model for Holly Golightly ends up mad bag lady’ – casts a long shadow over her work, particularly this side of the Atlantic, where none of her books was published in her lifetime. It’s arguable, in fact, that the subsequent biography of her, as much as the work itself, was responsible for the mini-revival she underwent at the turn of the millennium. You can see why. ‘Mad, destitute writer’ makes good copy. Add to that the Breakfast at Tiffany’s glamour, and the tragic-downfall articles write themselves.

I was lucky to come across the essays when I was too young to know about the New Yorker, never mind Maeve Brennan. To me, they were just prose snapshots of city life taken by an archetype with which – having been raised in a busy city myself – I was familiar: the quietly eccentric urban solitary. And that first impression lingers. I see her in every city I visit.

In the earliest pieces, the Long-Winded Lady is a two-dimensional comedic persona, that of a well-heeled suburbanite shopping her way around the nicer parts of Manhattan. But as the essays keep coming, the character deepens. A noticeable change occurs in 1960, when Brennan, aged 43, goes through a divorce and, after time spent away, returns to the city alone. The humour turns brittle, and melancholy, hitherto repressed, starts to predominate. The Long-Winded Lady from this point comes very close indeed to reflecting her writer’s character and its vicissitudes.

Keeping to her parts of Manhattan – Midtown and Greenwich Village mainly – the Long-Winded Lady eavesdrops on ‘the most cumbersome, most reckless, most ambitious, most confused, most comical, the saddest and coldest and most human of cities’, as Brennan calls it in her note to the 1969 collection. Sometimes she watches the world from her window or, if her current room has one (she moves a lot), her balcony. Mostly she’s out, though, ambling through the most vital, open streets in the world. She hears that a wooden farmhouse is being transported from Uptown to Greenwich Village and goes to see it (‘Charles Street is a nice street, a good place for a house to move to’). She visits the local haberdashery to inspect the damage from a fire whose smoke she saw the night before. She watches a parade, or a protest. She shops for shoes or books or, once, ‘one of those plain glass orange squeezers’. Her favourite activity, though, is watching the goings-on in ‘small, inexpensive restaurants’, which she believes are ‘the home fires of New York City’.

‘It is not the strange or exotic ways of people that interest her,’ Brennan writes in the same note, ‘but the ordinary ways, when something that is familiar to her shows.’ Her style is built upon this ordinariness, and it’s one of the reasons she was referred to – when referred to at all – as Chekhovian. Her metaphors, like his, manage to be both rich and remarkably close to their occasion: a man enters a restaurant with a bundle of newspapers ‘which had been opened and folded back carelessly so they looked half inflated and as though they might start to rise, like a soufflé, at any minute’. Chekhovian too is the way she matter-of-factly deals with the peculiarities of ordinary perception, as when describing the view from a restaurant window that’s partly below street level: ‘you see . . . halves of men and women, whole children, and dogs complete from nose to tip of tail’. Where she differs from Chekhov, though, is in her inevitable return to introspection. This is how that observation ends: ‘It is both soothing and interesting to watch people without being able to see their faces. It is like counting sheep.’ This is less like Chekhov and more like a character in Chekhov. That’s the better way to think about it: the Long-Winded Lady pieces are not so much stories as soliloquies. Hers is the only consciousness we really inhabit.

That isn’t to say her world is full of stick figures, though. People are merely observed and briefly noted, yet how vivid they are. In the phrase used by Ford Madox Ford, they are quickly ‘got in’. Ford, to illustrate this point, uses a Maupassant sentence: ‘He was a gentleman with red whiskers who always went first through a doorway.’ ‘That gentleman’, Ford writes, ‘is so sufficiently got in that you need no more of him to understand how he will act.’ The same could be said of many of the Long-Winded Lady’s characters. Take for example ‘The Man Who Combs His Hair’ (1964): ‘There is a man around this neighbourhood who is always combing his hair. Once I saw him borrow a comb from a very small shoeshine boy. Then, while he combed his hair, combing it with one hand and smoothing it with the other, he bent and looked into the child’s face as though the little face were a mirror – only a mirror, and nothing more than that.’

Her sensitivity to people, and her ability to vivify them with only a brief sketch, must have had something to do with my delay in grasping one of the essential – and terrifying – facts about the Long-Winded Lady: she is only ever alone. No matter how many fellow New Yorkers she observes, she’s never actually with any of them. She dines alone, drinks alone, shops alone, walks alone, lives alone. She talks only to the odd stranger (almost always reluctantly), and shop, hotel, bar and restaurant staff. Even in a piece about a New Year’s Eve gathering – fourteen of whose attendees she names and evidently knows well – she seems apart, an observer watching alone.

It’s hard to think of anyone other than maybe Rilke or Pessoa whose work this sort of loneliness pervades so strongly. And yet this is someone at the very centre of cosmopolitan society: a New Yorker staff writer who has romances with some of the magazine’s biggest names and is friends with Capote, Gerald and Sara Murphy (on whom Fitzgerald based the Divers of Tender Is the Night), Edward Albee . . .

Her friend Roger Angell’s verdict – ‘She wasn’t one of us; she was one of her’ – approaches it. It’s not so much a physical as an inner apartness – one that, usually, she’s comfortable with. Look at the Long- Winded Lady’s peculiar attitude towards seeing celebrities on the streets: ‘I like recognizing them . . . and knowing that by just being where I am they make me invisible.’ That apartness is also there, though less comfortably, in her occasional bitterness when describing groups or couples enjoying themselves. Of a woman strolling with her boyfriend, she writes: ‘Her hair had been bleached and dyed so often that it was weathered to a rough rust-pink, and it hung stiffly down her back like a mane, or like wig hair before it has been brushed and combed and curled into shape.’ She goes on: the couple ‘were the same height (five feet four or so) and about the same weight (a hundred and sixty pounds)’. There’s something fearful about such a cruel eye. It makes the beholder herself seem fragile and exposed.

The Long-Winded Lady reserves her sympathy almost exclusively for animals, trees and those lower in society. ‘I like pigeons,’ she writes. ‘I cannot imagine where they get their pampered air, but they have it and I like them for having it.’ She gives ‘a cheer for the clean- ing lady’ who, telling the press of coming across a bag of jewels, said, ‘My eyes popped out . . . I couldn’t resist first trying on a few rings and bracelets.’ And when beggars ask her for money, she gives it.

She’s also gentle (though slightly mocking in a collegial way) with fellow solitaries. She admires, for example, a woman she encounters while shopping, who hums while she browses: ‘Every time she saw something that interested her, her humming rose a little, and by the time she went off to the fitting room, with several dresses, she had almost achieved a soft chant of triumph.’

Towards the city itself – which, directly or indirectly, is her work’s focus – the Long-Winded Lady is fiercely ambivalent. It’s clear that she loves it. Yet she seems to love it against her will – particularly in her middle and later years, when Manhattan was the chaotic site of one of the biggest building booms in history. Midtown especially suffered at the hands of so-called urban renewal: whole areas were demolished to make way for skyscrapers – areas Brennan knew well, and had often lived in. As early as 1955 the Long-Winded Lady was prophesying (correctly): ‘All my life, I suppose, I’ll be scurrying out of buildings just ahead of the wreckers.’

She saw first hand that such vandalism was the death of many New York neighbourhoods. Though far from perfect, these were self-sustaining, integrated communities, in which people walked to work, watched their streets, knew one another – places whose small businesses were run by the locals who owned them. Their destruction, combined with city-wide problems such as financial turmoil, the departure of industry and the middle classes, and a drug epidemic, also led to a rapid rise in crime. Between 1959 and 1971 (the bulk of her career), killings in New York more than quadrupled.

You can see the decline by looking at the films from that period. The harshly glamorous Times Square of The Sweet Smell of Success (1957) becomes, in just over a decade, the crime-ridden sleaze-pit of Midnight Cowboy (1969). By the time you get to Taxi Driver in 1976, Manhattan is close to its nadir. This isn’t just cinematic over- statement, either. In 1975, the city was at its lowest point since the Depression, almost going bankrupt. It wasn’t until 1981, the year of the Long-Winded Lady’s final letter, that it finally balanced the books and began to revive.

‘These days I think of New York as the capsized city,’ Brennan writes in the 1969 note. ‘Half-capsized, anyway, with the inhabitants hanging on, most of them still able to laugh as they cling to the island that is their life’s predicament.’ She herself was one such inhabitant – though, in the later pieces at least, she’s seldom laughing. The artful reticence and gentle mockery of the Long-Winded Lady’s early stories make way for full-throated despair, as in one of her most revealing pieces, ‘I Look Down from the Windows of This Old Broadway Hotel’ (1967). This is the centre of New York’s theatrical and entertainment area, she writes, but what joviality and good fellowship exist here are thin; the atmosphere is of shabby transience, and its heart is inimical. It is a run-down neighbourhood of cheap hotels and rooming houses and offices and agencies and studios and restaurants and bars, and of shops that pack up and disappear overnight . . . The blank windows reflect an extremity of loneliness – that mechanical city loneliness which strays always at the edge of chaos, far from solitude . . . Ordinary life used to be lived [here] . . . but it has come to be hardly more than a camping ground for strollers and travellers and tourists and transients of every kind.

‘A few people stay,’ she goes on, and in a sad reverie she imagines one: ‘an old woman living by herself in a single hotel bedroom’ who, suddenly fearful but without anyone to talk to, ‘tries to tell the room clerk of what is threatening her’. He listens, ‘but he has heard her story many times before, from other people, in other years and in other defeated places like this one’. In the light of Brennan’s own future – alone, poor, paranoid, drifting from one seedy single hotel room to another on nearby 42nd Street (which the New York Times once called ‘the worst block in town’) – it’s upsettingly prescient. But, fortunately, the Long-Winded Lady’s long-windedness offers something else on which to close. It might be my favourite of her endings, managing to be somehow both dreamlike and grounded, and with that characteristic note, in its final line, of faint, faint hope.

‘I heard’, she writes, ‘the music of a very small band – and the tune being played was small and sweet and noticeably free: elfin music.’ (That odd adjective was often used to describe Brennan herself.) Then ‘a man came into view . . . He was the band.’ After describing, minutely, this one-man band’s equipment, she writes, ‘He banged the drum and blew the trumpet and clashed the cymbals and piped on a little pipe, but although the street was fairly busy, nobody gave him any attention . . .’ Suddenly, a car, racing into the nearby car- park, brushes him. ‘I got a fright,’ writes the Long-Winded Lady, but the musician showed no sign of fright, or anxiety, or anger – not a sign of interest. He continued banging the drum, clash- ing the cymbal, blowing the trumpet; his music never faltered. Imperturbable, he advanced along his way and passed out of my sight behind the little houses just below me . . . I thought he might turn around and come back to Broadway this way, but he did not come back – at least, not while I waited.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 59 © Kristian Doyle 2018

About the contributor

KRISTIAN DOYLE is a writer who lives in Liverpool. He is currently at work on a novel.