To the dismay of many professional biographers (and, one hopes, some of their readers), the Biography sections of most bookshop chains these days seem to display not the well-researched and elegantly written lives of interesting people, but celebrity memoirs or ‘auto’biographies of the more or less famous. Since many celebrities are famous merely for being famous, their stories are often not very interesting. A new lease of life, however, has been given to the memoir racket by the so-called ‘misery memoir’, or ‘Mis-lit’, which relates the story of a wretched childhood full of hardship, abuse and general awfulness, all recorded in graphic detail. The popularity of these books is a mystery to me. Perhaps it lies in the inspiration of heroic victory over early disadvantage. More likely, I suspect, reading about other people’s misery has become the ideal spectator sport.

If one were searching for the perfect antidote to Mis-lit one would find it triumphantly in Gerald Durrell’s My Family and Other Animals. First published in 1956 and in print ever since, the book is surely one of the most enjoyable English memoirs of the second half of the twentieth century. Every page is a celebration of the colours, sounds, smells, tastes and tactile sensations of the then unspoilt island of Corfu where the Durrell family arrived in March 1935 and where they lived until their expulsion from Eden in 1939 on the outbreak of war. It is beautifully written, with some astonishingly vivid and exact descriptions, whether of capturing a water snake in a stream or watching a lizard in its progress across a nocturnal ceiling, and it gets away, effortlessly, with all sorts of things one isn’t meant to get away with, not least the antics and tics of Funny Foreigners.

The twin prongs of its success are the joyful evocation of fauna and flora on this idyllic island and the acutely observed social comedy. Durrell was expert in both. Though the Durrell

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inTo the dismay of many professional biographers (and, one hopes, some of their readers), the Biography sections of most bookshop chains these days seem to display not the well-researched and elegantly written lives of interesting people, but celebrity memoirs or ‘auto’biographies of the more or less famous. Since many celebrities are famous merely for being famous, their stories are often not very interesting. A new lease of life, however, has been given to the memoir racket by the so-called ‘misery memoir’, or ‘Mis-lit’, which relates the story of a wretched childhood full of hardship, abuse and general awfulness, all recorded in graphic detail. The popularity of these books is a mystery to me. Perhaps it lies in the inspiration of heroic victory over early disadvantage. More likely, I suspect, reading about other people’s misery has become the ideal spectator sport.

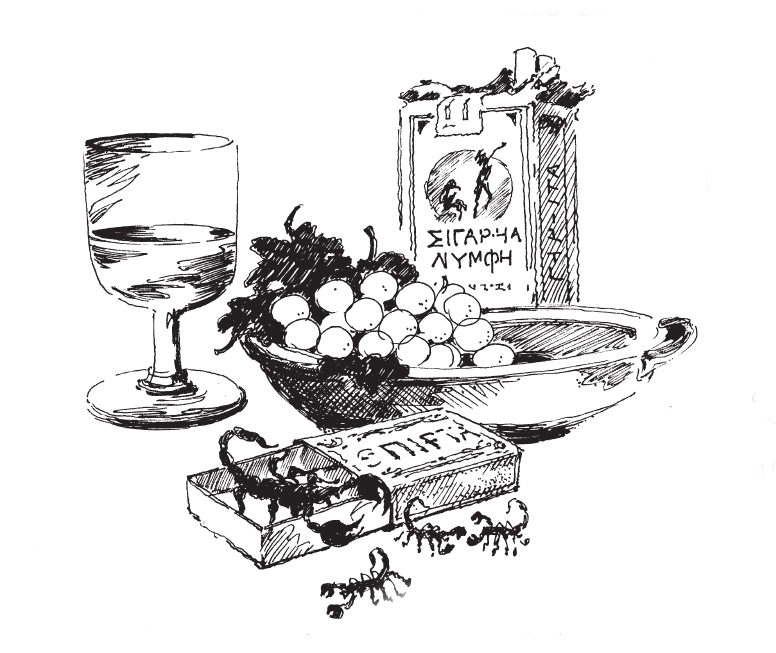

If one were searching for the perfect antidote to Mis-lit one would find it triumphantly in Gerald Durrell’s My Family and Other Animals. First published in 1956 and in print ever since, the book is surely one of the most enjoyable English memoirs of the second half of the twentieth century. Every page is a celebration of the colours, sounds, smells, tastes and tactile sensations of the then unspoilt island of Corfu where the Durrell family arrived in March 1935 and where they lived until their expulsion from Eden in 1939 on the outbreak of war. It is beautifully written, with some astonishingly vivid and exact descriptions, whether of capturing a water snake in a stream or watching a lizard in its progress across a nocturnal ceiling, and it gets away, effortlessly, with all sorts of things one isn’t meant to get away with, not least the antics and tics of Funny Foreigners. The twin prongs of its success are the joyful evocation of fauna and flora on this idyllic island and the acutely observed social comedy. Durrell was expert in both. Though the Durrell family had been for many generations Anglo-Indians (Lawrence, the eldest son, memorably described, with horror, his first encounter with England, at the age of 11), this is a consummately English book: the self-deprecating humour, the comic deflations, the making light of serious matters, the profound attention to unserious things, and the pretence that, to well-bred people on a private income, nothing really matters very much and the future can very probably take care of itself (‘“Yes, dear,” said Mother, vaguely’, is a constant refrain when a crucial decision has to be taken). The Durrells may have thrown themselves into Corfiot life with great energy and verve but they remained profoundly English. They had arrived from wet and windy Bournemouth, where their money (there are occasional references to problems with banks that don’t seem to have hampered the takingon of leases on various yellow and pink villas dotted about the island) and their patience with the Home Counties weather were running out at about the same time. Apart from the animals, the family consisted of Mother – dreamy, fond of her kitchen and her preserves, indulgent towards her children and only a fitful disciplinarian when things seemed to have gone rather too far – and four children: Lawrence, with his typewriter, advanced views, racy Bohemian friends and high literary aspirations; Gerald, the youngest, with his boyish passion for insects and birds and every kind of creature; Leslie, with his sporting guns and shooting magazines; and Margo, with her spots and sun-cream, tantalizing the local youth with her exposed limbs and with her habit of persistently getting proverbs completely wrong. In the English manner, Gerald’s reporting of their goings-on is both comic and lethal. In particular he manages to make fun of his elder brother’s literary aspirations in prose which is itself exquisitely supple, precise and lyrical, leaving the reader in no doubt that the two are equal masters. The best comic passages are those which combine the exploits of the youthful naturalist with the not always sympathetic reactions of his family who found themselves, whether they liked it or not, inside a makeshift, and seemingly rather dangerous, zoo. In a crumbling wall that surrounded the sunken garden of the daffodil-yellow villa, among the toads and geckos, the lizards and the slow-worms, tiny black scorpions lurked under the flaking plaster. Gerald found them to be ‘pleasant, unassuming creatures, with, on the whole, the most charming habits’. His family were not disposed to agree, as that lethal clause ‘on the whole’ indicates. One day he found a female scorpion covered with a mass of tiny babies. Delighted with this find, he popped it into a matchbox and went in to lunch, quite forgetting that he had left it on the mantelpiece. When lunch was finished Lawrence went out to find some matches to light his cigarette and returned to the table: ‘Oblivious of my impending doom I watched him interestedly as, still talking glibly, he opened the matchbox.’ In his account of what happened next Gerald insisted ‘that the female scorpion meant no harm’. Even so, he considered it prudent to spend the rest of the afternoon on the hillside. In addition to such gloriously comic episodes there are also the unforgettable local characters: the astonishing Rose-beetle Man with his buzzing beetles restrained by strings, piping his pastoral melodies along the dusty island roads; Spiro, the family’s eternal fixer and protector, comically prone to mispronunciation and to a prodigiously incorrect use of the plural (to him Mrs Durrell is always ‘Mrs Durrells’); and, above all, the wholly engaging figure of the doctor, Theodore Stephanides, shy, tentative, master of terrible puns, and expert naturalist and botanist. It was a time when middle-aged men could take young boys under their wing for instruction without fear of an anonymous phone-call to Childline, and one cannot help thinking that some of the delicate charm of the Durrell persona is rooted in the example of this gently civilized man, with his unforced erudition, scientific instruments and multiple specimen-boxes. In addition, a cast of loud women-in-black, sleepy shepherds pouring out an afternoon glass of krasí on a vine-shaded terrace, and pompous customs officials populate the book. And then there is Corfu itself, looked down on by Gerald with his faithful and almost-human canine companion, Roger:The island dozed below us, shimmering like a water-picture in the heat-haze: grey-green olives; black cypresses; multicoloured rocks of the sea-coast; and the sea smooth and opalescent, kingfisher-blue, jade-green, with here and there a pleat in its surface where it curved round a rocky, olive-tangled promontory. Directly below us was a small bay with a crescent-shaped rim of white sand, a bay so shallow, and with a floor of such dazzling sand that the water was a pale blue, almost white.This easy, sensually rich, endlessly instructive and surprising, sunlit childhood is the source of the magic of this book. It is the childhood each of us would have wanted and Gerald Durrell had it, together with the gift of recreating it vividly and with humour. My Family and Other Animals is a joyful celebration of life and colour and perfect living. When the Durrells arrived at their first villa, ‘The warm air was thick with the scent of a hundred dying flowers, and full of the gentle, soothing whisper and murmur of insects. As soon as we saw it, we wanted to live there – it was as though the villa had been standing there waiting for our arrival. We felt we had come home.’ That homeward journey, or nostos in Greek, was one that Gerald and Lawrence spent the rest of their lives trying to complete. After the Corfu idyll neither found it and the search continued, but My Family and Other Animals lives on, in spite of the subsequent horrors of the war years, and in spite of the depredations of the tourist industry on the island of Corfu. Durrell completed two more books about his island experiences but the first was the best – a book never to be forgotten or to be parted from.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 18 © Nicholas Murray 2008

About the contributor

Nicholas Murray is the author of two novels, a collection of poems, and five literary biographies. His book on British Victorian travellers, A Corkscrew Is Most Useful, has just been published.