Somewhere in the badlands of Utah is a canyon called Davis Gulch. Centuries ago, the Ancestral Pueblo carved a dwelling in its rock, now inscribed with the words ‘NEMO 1934’. This is the last known signature of the vagabond Everett Ruess.

The epithet ‘vagabond’ was his own, and rarely has the term been so richly deserved. An aspiring artist and writer from a bohemian home in Los Angeles, Ruess set out at the age of 16 on an uncompromising quest to seek out beauty and solitude in the rugged wilderness of the American south-west. Over the next four years he travelled the mountains, deserts and canyon-lands of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah, alone but for the company of his burro and occasionally a dog. At the age of 20 he disappeared. ‘NEMO’ might have been a reference to Captain Nemo from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea – another notable seeker of solitude – or else the Greek for ‘No Man’, as employed by Odysseus.

A Vagabond for Beauty (1983), edited by W. L. Rusho – a federal government employee who became fascinated with Ruess’s story – is a compilation of the young man’s diary entries, letters to his parents, brother and friends, fragments of prose and poetry, and linoleum landscape prints that he produced in the four years leading up to his disappearance. The book fell into my hands in a suitably serendipitous manner, dropped through my letterbox by a neighbour who knew I was on the look-out for forgotten or unusual travel books.

Straightaway I was hooked. I’ve also travelled in solitude, walking for weeks and months on end, but no sooner have I been immersed in true wilderness than I’ve found myself on the other side, looking back with a bittersweet blend of relief and disappointment. With Ruess there was no looking back. His commitment awed and alarmed me in

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inSomewhere in the badlands of Utah is a canyon called Davis Gulch. Centuries ago, the Ancestral Pueblo carved a dwelling in its rock, now inscribed with the words ‘NEMO 1934’. This is the last known signature of the vagabond Everett Ruess.

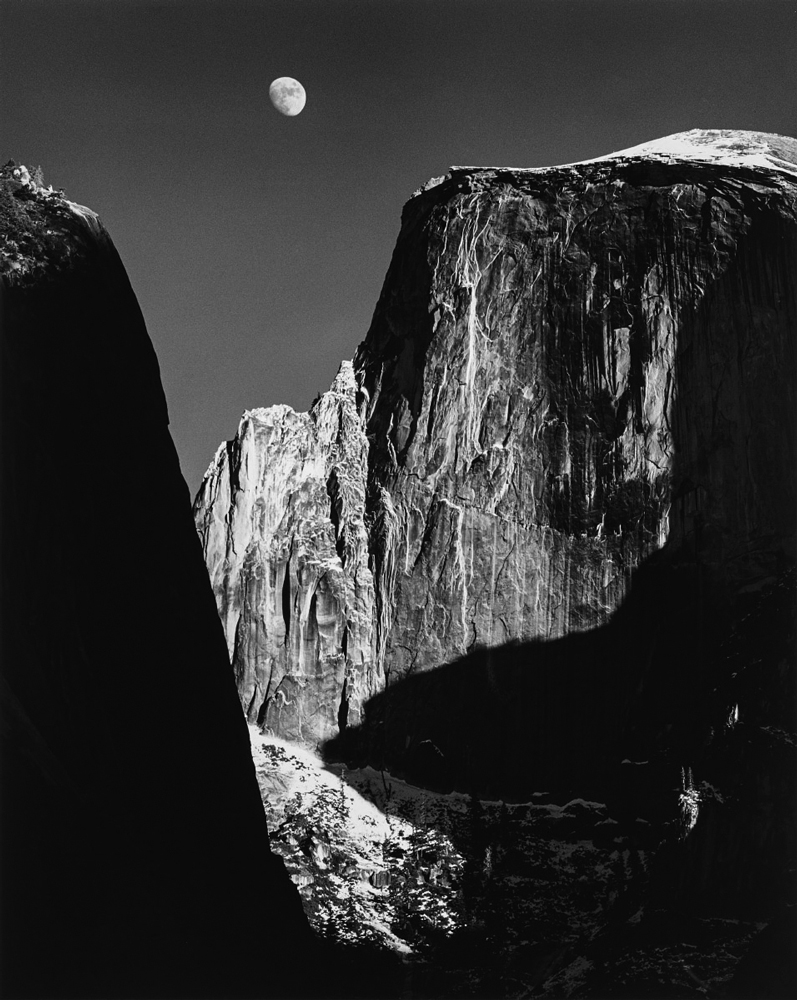

The epithet ‘vagabond’ was his own, and rarely has the term been so richly deserved. An aspiring artist and writer from a bohemian home in Los Angeles, Ruess set out at the age of 16 on an uncompromising quest to seek out beauty and solitude in the rugged wilderness of the American south-west. Over the next four years he travelled the mountains, deserts and canyon-lands of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah, alone but for the company of his burro and occasionally a dog. At the age of 20 he disappeared. ‘NEMO’ might have been a reference to Captain Nemo from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea – another notable seeker of solitude – or else the Greek for ‘No Man’, as employed by Odysseus. A Vagabond for Beauty (1983), edited by W. L. Rusho – a federal government employee who became fascinated with Ruess’s story – is a compilation of the young man’s diary entries, letters to his parents, brother and friends, fragments of prose and poetry, and linoleum landscape prints that he produced in the four years leading up to his disappearance. The book fell into my hands in a suitably serendipitous manner, dropped through my letterbox by a neighbour who knew I was on the look-out for forgotten or unusual travel books. Straightaway I was hooked. I’ve also travelled in solitude, walking for weeks and months on end, but no sooner have I been immersed in true wilderness than I’ve found myself on the other side, looking back with a bittersweet blend of relief and disappointment. With Ruess there was no looking back. His commitment awed and alarmed me in equal measure. His first letters home read like snippets from The Boy’s Own Annual – ‘I slept in the middle of a pocket in the sand dunes, building my fire just at dusk . . . I had a jolly time yesterday, tramping up and down the beach’ – but one of the joys of this book is witnessing the growth not only of a man but of a writer. He gets better over time, restlessly reworking thoughts and descriptions, honing and improving his prose as if whittling sticks by the campfire. Ruess’s type of vagabonding has nothing to do with shiftlessness; he takes his vocation seriously and uses the freedom it affords to apply himself with discipline to the craft, and the daily graft, of writing. For sure, he can be overindulgent: ‘Once more I am roaring drunk with the lust of life and adventure and unbearable beauty.’ But it is precisely this lack of filter and this romantic extravagance that result in some of the rawest and most luminous nature writing I’ve ever read. Ruess really means it. ‘As I stalked down from the high perched plain, lightning flashed out from the darkening sky; thunder rolled and reverberated in the narrow canyon,’ he writes after witnessing a desert storm. ‘A vivid arrow flare of piercing brilliancy struck down at the red cliffs, ricocheting with a sickening whine, like a hurtling shell.’ Time and again, the sublime strikes him with the force of lightning, making his prose so electrically charged it can be painful. ‘I have seen almost more beauty than I can bear,’ he writes in one of his letters. Elsewhere he describes ‘such utter and overpowering beauty as nearly kills a sensitive person’. This acute sensitivity to beauty places Ruess in a long line of ecstatic American experience-seekers from Walt Whitman to Allen Ginsberg and Edward Abbey. Paul Kingsnorth, who wrote the introduction to a new edition of A Vagabond for Beauty in 2021, describes him as ‘a young, green nature mystic . . . one of those gifted with an aerial through which could flow the divine presence from the Earth itself. This sounds overblown, maybe, but that makes it no less real.’ Despite his predilection for solitude, Ruess was part of West Coast literary and artistic circles that included the poet Robinson Jeffers, the painter Edward Weston (‘a very broad-minded man’), and the photographers Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange, all of whom were moved and inspired by the landscapes of the American West even as man was encroaching on the wilderness. That frontier had long since gone, and the beauty and solitude Ruess described were vanishing even as he wrote about them. The fact of his youthful disappearance also draws inevitable comparisons with Chris McCandless (a.k.a. Alexander Supertramp) who died in Alaska in 1992, immortalized by Jon Krakauer in Into the Wild (1996). Like McCandless, Ruess was dissatisfied with American society, consciously turning his back on the corruption of civilization. He mostly avoided the company of the region’s white traders and settlers and – after initial ungracious impressions (‘The Navajo live in filth’) – increasingly came to admire the Navajos, Hopis, Pueblos and Utes who had lived in these harsh desert landscapes for generations. ‘I have often stayed with the Navajos,’ he writes in 1934. ‘I’ve known the best of them, and they are fine people. I have ridden with them on their horses, eaten with them and even taken part in their ceremonies. Many are the delightful encounters, and many the exchange of gifts.’ He started to learn the Navajo language, attended a traditional Hopi Snake Dance and joined archaeological digs at Ancestral Pueblo sites. Which brings us to his last known whereabouts at the rock dwelling in Davis Gulch, where he carved that enigmatic inscription before vanishing forever. Of the many theories about his disappearance, two involve Native Americans: perhaps he married a Navajo woman and renounced his white identity; or perhaps he was murdered by Jack Crank, a notorious Navajo outlaw. Alternatively, he was killed by white cattle-rustlers after stumbling on a crime and needing to be silenced. One witness claimed that a local drunk had bragged about shooting the ‘goddamned artist kid’ and throwing his body in the Colorado River, but no one believed he was capable of it; when W. L. Rusho interviewed this man in 1982 he was suffering from memory loss and seemed to know nothing about it. Or did Ruess choose to die in solitude and commit suicide? Many of his statements could certainly be interpreted this way. ‘[H]e who has looked long on naked beauty may never return to the world,’ he wrote, and: ‘I’ll never stop wandering. And when the time comes to die, I’ll find the wildest, loneliest, most desolate spot there is.’ Given that he vanished soon afterwards, some have taken him at his word. But what romantically minded adolescent hasn’t made similar claims? Unlike many vagabonds, Ruess wasn’t running away from stifling family expectations or an unhappy home. The letters he exchanged with his family are loving and conversational, and both his parents seemed to be relaxed – even remarkably supportive – about their son’s unconventional urge to wander the world alone. It is hard to imagine him killing himself, knowing the heartbreak it would bring. But deserts are strange places. They bring dreams and visions. In the end, we will never know the twists his mind might have taken. Perhaps the likeliest explanation is that he fell into a ravine or broke his leg in the middle of nowhere, dying of injuries or thirst. His bones would have been carried off by vultures and coyotes. In this, his body would have shared a similar fate to that of Edward Abbey, who asked his eco-anarchist friends to wrap his corpse in an old sleeping-bag and dump it (illegally) in the Sonoran Desert where it would never be found. Seven years before that occurred, Abbey wrote ‘A Sonnet for Everett Ruess’:Hunter, brother, companion of our days: that blessing which you hunted, hunted too, what you were seeking, that is what found you.For someone who was so young when he vanished and who never wrote a book, it is remarkable how far Ruess’s influence stretches, like a desert shadow. There is always the danger that Ruess’s life story, and the mystery of his disappearance, will overshadow his work, which would be a pity. A Vagabond for Beauty is a masterpiece, in the original sense of the word: not the culmination of someone’s ambition and the best thing they will ever make, but the piece by which they graduate from being a novice to becoming a master of their chosen craft. Already a master vagabond, Ruess was learning to master his art when his road was cut short by whatever fate befell him. Today, as the wilderness that he loved shrinks ever more rapidly, his unembarrassed worship of nature – and his exuberant love of life – feel more important and more exciting than ever.

I thought that there were two rules in life – never count the cost, and never do anything unless you can do it wholeheartedly. Now is the time to live.Rather than ‘NEMO’, this excerpt from his diary could be his epitaph.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 78 © Nick Hunt 2023

About the contributor

Nick Hunt is the author of three travel books, most recently Outlandish: Walking Europe’s Unlikely Landscapes (2021), a work of gonzo ornithology and a short-story collection. He is also co-director of the Dark Mountain Project. You can hear him in Episode 42 of our podcast, discussing the travel writing of Patrick Leigh Fermor with Artemis Cooper.