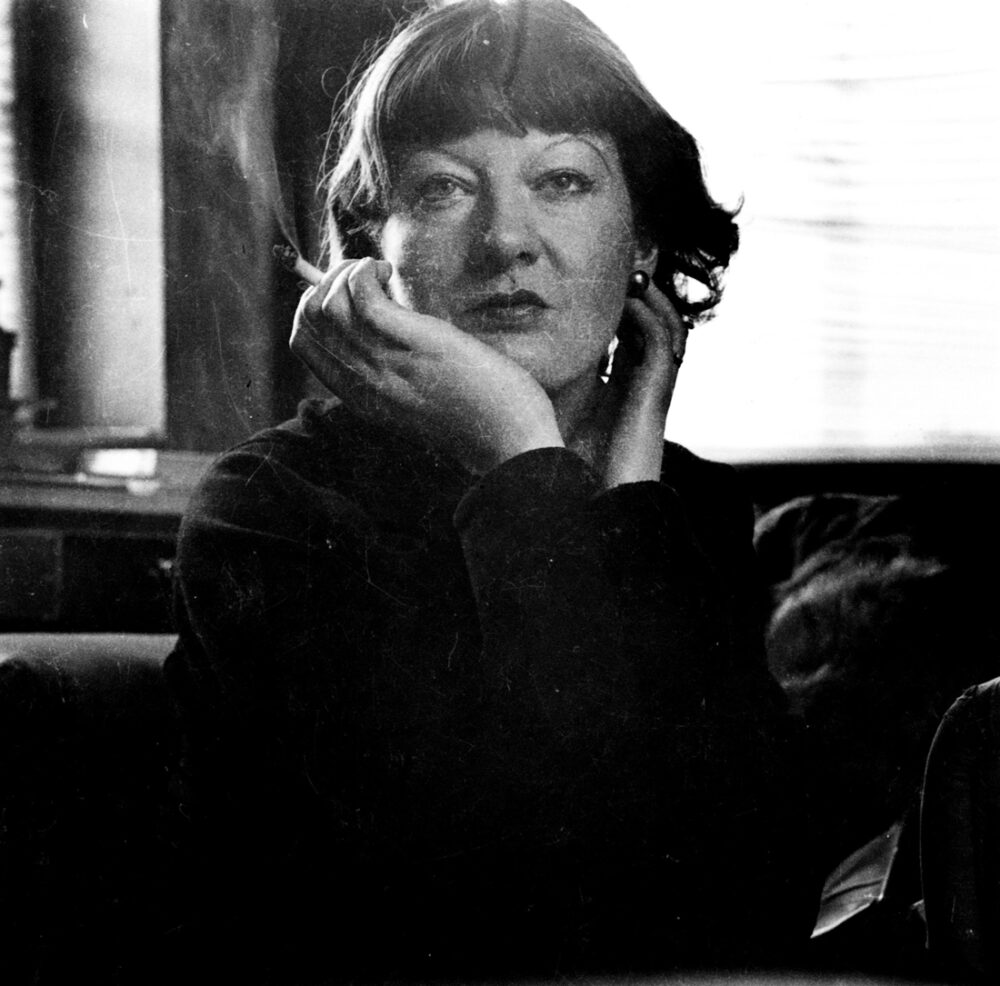

Julia Strachey was a writer of rare talent and originality who, in a lifetime of writing, managed to complete and publish only two novels and a number of sketches and short stories. I knew nothing of her until I happened to come across a Penguin reprint of those novels, Cheerful Weather for the Wedding and An Integrated Man. I was immediately bowled over by their brilliance and originality, and was surprised to discover that, in effect, they are all there is. What stopped this gifted writer from finishing and publishing more?

It’s not that her work wasn’t in demand. When Cheerful Weather for the Wedding was published in 1932, it met with a very warm reception. The literary editor of the New Yorker was so impressed that he wrote to Julia and offered to publish anything she cared to send him. Her response was to send nothing for a quarter of a century, until in 1958 she obliged with a sketch, which was duly published – but not until Julia had fought at length, and successfully, to have every single editorial alteration to her piece reversed. Clearly this was not a woman with a strong sense of how to build a literary career.

It isn’t hard to see why Cheerful Weather so impressed its early readers. A cool, darkly comic account of an upper-middle-class wed- ding day in Dorset, it is brisk, deftly managed, sharply observed and crisply written, without a word wasted. But, more than that, there is something in its tone that is unique – something ‘airy and translucent’, as one critic put it. Strachey herself said, rather cryptically, that her aim was to convey a ‘phosphorescent’ impression, and there is a strange luminosity about some of the descriptive passages, in which the author focuses her attention so fixedly on something that it seems to develop a faint unearthly glow. Here she is on a pot of ferns:

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inJulia Strachey was a writer of rare talent and originality who, in a lifetime of writing, managed to complete and publish only two novels and a number of sketches and short stories. I knew nothing of her until I happened to come across a Penguin reprint of those novels, Cheerful Weather for the Wedding and An Integrated Man. I was immediately bowled over by their brilliance and originality, and was surprised to discover that, in effect, they are all there is. What stopped this gifted writer from finishing and publishing more?

It’s not that her work wasn’t in demand. When Cheerful Weather for the Wedding was published in 1932, it met with a very warm reception. The literary editor of the New Yorker was so impressed that he wrote to Julia and offered to publish anything she cared to send him. Her response was to send nothing for a quarter of a century, until in 1958 she obliged with a sketch, which was duly published – but not until Julia had fought at length, and successfully, to have every single editorial alteration to her piece reversed. Clearly this was not a woman with a strong sense of how to build a literary career. It isn’t hard to see why Cheerful Weather so impressed its early readers. A cool, darkly comic account of an upper-middle-class wed- ding day in Dorset, it is brisk, deftly managed, sharply observed and crisply written, without a word wasted. But, more than that, there is something in its tone that is unique – something ‘airy and translucent’, as one critic put it. Strachey herself said, rather cryptically, that her aim was to convey a ‘phosphorescent’ impression, and there is a strange luminosity about some of the descriptive passages, in which the author focuses her attention so fixedly on something that it seems to develop a faint unearthly glow. Here she is on a pot of ferns:The transparent ferns that stood massed in the window showed up very brightly, and looked fearful. They seemed to have come alive, so to speak. They looked to have just that moment reared up their long backs, arched their jagged and serrated bodies menacingly, twisted and knotted themselves tightly about each other, and darted out long forked and ribboning tongues from one to the other; and all as if under some terrible compulsion . . . they brought to mind travellers’ descriptions of the jungles in the Congo – of the silent struggle and strangulation that vegetable life there consists in.Strachey writes as if seeing those ferns for the first time, and her gaze is intense and appalled; she senses the menace lurking in the everyday objects that gather around us. The dominant figure in Cheerful Weather is not the reluctant bride, who is quietly getting drunk – or her rejected suitor, who is rather more noisily getting drunk – but Mrs Thatcham, the bride’s mother, a human whirlwind who is typically to be found

rushing around the room on tiny feet, snapping off dead daffodil heads from the vases, pulling back window curtains, or pulling them forward, scratching on the carpet with the toe of her tiny shoe where a stain showed up. All this with a sharp anxiety on her face as usual – as though she had inadvertently swallowed a packet of live bumble-bees and was now beginning to feel them stirring about inside her.

At ten minutes to one the postman had appeared . . . And certain cows, those that had lost their calves, on perceiving his red bicycle from afar, charged joyfully across the field in a bunch, imagining he was bringing back to them their stolen children. When they had realized their mistake, they had stood and trumpeted shrilly as usual for half an hour. Then luncheon – and a massed rendezvous of flies! . . . After lunch the cows had suddenly begun to bellow again. The flies, however, had dropped off to sleep.And here, later, are the flies again:

All of a sudden the flies on the window-pane woke up and started to rage together with a venomous zizzing. One amongst them began to boom deafeningly and to throw its scaly body repeatedly against the glass. Others, too, began to boom in the same echoing manner, and soon all of them together were hurl- ing their scaly bodies against the pane. One could imagine that packets of tintacks were being showered again and again at the glass.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 69 © Nigel Andrew 2021

About the contributor

Nigel Andrew is a writer, reviewer and blogger. He has recently written The Mother of Beauty (2019), about the golden age of English church monuments and other matters of life and death.