When Slightly Foxed was young, only a few issues old in fact, the writer Christopher Hawtree came to us with the story of P. Y. Betts and her childhood memoir People Who Say Goodbye. We loved the book, and a piece about it by Christopher appeared in Issue 7. Now, several years later, we’re delighted to have the chance to issue People Who Say Goodbye as a Slightly Foxed Edition.

P. Y. Betts was one of those mysteriously disappearing authors, successful early on as a short-story writer and contributor to Graham Greene’s prestigious but short-lived magazine Night and Day, which was scuppered by a libel suit in 1937. In the 1930s she also published French Polish, a funny and sharply observed novel about a girls’ finishing school. She was then heard of no more until, fifty years later, the writer Christopher Hawtree came across her name in the British Library and ran her to ground, living contentedly alone on a remote smallholding in Wales. Encouraged by a publisher, she took up her pen again and wrote People Who Say Goodbye.

The unconventional course of P. Y. Betts’s literary life seems all of a piece with her character. There is a humorous, clear-eyed detachment about her view of the world and those around her – no doubt inherited from her energetic, forthright mother and her father, a laid-back character always ready with a joke, who refused to kow-tow to his superior in-laws – that tells you she was always going to be her own person; someone, indeed, whose voice is as wonderfully alive and individual today as it was seventy years ago.

She was born in 1909, in a house on the edge of Wandsworth Common. Up the road was a military hospi

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhen Slightly Foxed was young, only a few issues old in fact, the writer Christopher Hawtree came to us with the story of P. Y. Betts and her childhood memoir People Who Say Goodbye. We loved the book, and a piece about it by Christopher appeared in Issue 7. Now, several years later, we’re delighted to have the chance to issue People Who Say Goodbye as a Slightly Foxed Edition.

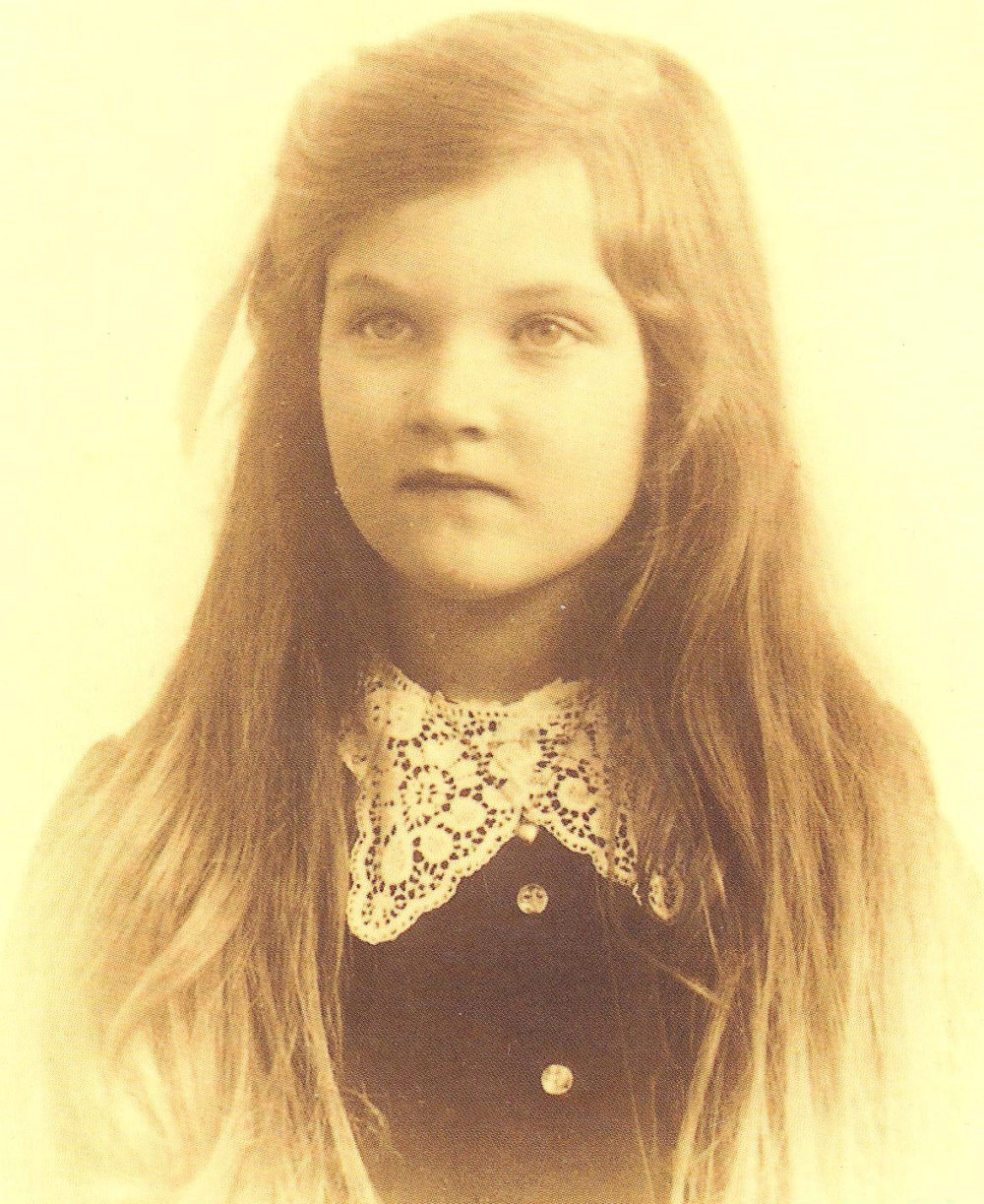

P. Y. Betts was one of those mysteriously disappearing authors, successful early on as a short-story writer and contributor to Graham Greene’s prestigious but short-lived magazine Night and Day, which was scuppered by a libel suit in 1937. In the 1930s she also published French Polish, a funny and sharply observed novel about a girls’ finishing school. She was then heard of no more until, fifty years later, the writer Christopher Hawtree came across her name in the British Library and ran her to ground, living contentedly alone on a remote smallholding in Wales. Encouraged by a publisher, she took up her pen again and wrote People Who Say Goodbye. The unconventional course of P. Y. Betts’s literary life seems all of a piece with her character. There is a humorous, clear-eyed detachment about her view of the world and those around her – no doubt inherited from her energetic, forthright mother and her father, a laid-back character always ready with a joke, who refused to kow-tow to his superior in-laws – that tells you she was always going to be her own person; someone, indeed, whose voice is as wonderfully alive and individual today as it was seventy years ago. She was born in 1909, in a house on the edge of Wandsworth Common. Up the road was a military hospital and past the house went funeral processions, several times a day at the height of the First World War.Over all loomed the great prison where, from time to time, a crowd would gather when a notice was posted on the main gate that a murderer had been be hanged. It was something the family took in its stride, but all this gave young Phyllis a sense of the fragility of life and the pain of loss that runs like an undercurrent beneath the book’s sparkling surface. Young soldiers coming to say goodbye before going off to the war, children encountered once but never forgotten, the little sewing box, lovingly repaired again and again, which her mother had inherited from a friend who died in childhood – all were reminders. The Betts household, however, was cheerfully non-conformist and deeply disapproved of by her mother’s snobbish family, including her spinster sisters Ada and Ethel, who lived on the other side of the Common. Ethel (who ‘looked weirdly like Lord Longford in drag’, as her niece decided later) had in fact once been sought in marriage, ‘though only by a curate’. Aunt Ada had received more than one proposal, and had actually been engaged to a young man described as ‘an organist at Balmoral’. But eventually both aunts had preferred the physical comforts of home, where their every whim was indulged, to the responsibilities of marriage. Chez Betts, life had a very different flavour. Phyllis’s mother took a robust attitude to what would now be called Health and Safety – described by Phyllis as her ‘learn-as-you-burn’ policy. Kitchen knives were kept sharp as razors, and from a young age Phyllis and her brother were allowed to use them for cutting up food and anything else they thought needed cutting up. They were allowed the freedom to roam and there was no nonsense about unsuitable friends. Her mother was certainly not one for euphemisms either. ‘“What happens to all those dead people who are put into graves?” I asked my mother. “They rot,” she replied, spreading dripping on toast.’ Various maids came and went, becoming family friends but then always moving on to ‘better themselves’. Another regular feature were the visits of Dr Biggs the family physician (known to her father as ‘Old Whhhen-and-Whhhatski’ because of his highly aspirated aitches) – immaculately dressed and preoccupied with the regularity of the ‘bow-els’ which he pronounced in two distinct syllables. And there was the fearful Mrs Milton, landlady of Brattle Place in Kent where, due to some mysterious family connection, the Betts spent their holidays – a virago with missing teeth and a protruding lower jaw. ‘The general effect was of a tusked boar – she could have rootled for truffles.’ Unaffected by any wind of change, Phyllis’s mother felt schools for girls were on the whole a waste of time, but when, after a few years at various cosy but unacademic establishments, including one where dictation was taken from the leaders in the Daily Mail, Phyllis failed to get into St Paul’s, her mother confronted the High Mistress, wanting to know the reason why. Which was that she had never properly been taught anything. She got in eventually with the help of two lady crammers, the Bebb sisters, whose father, an irritable figure weighed down by the superiority of a towering intellect, had once been a Senior Wrangler at Cambridge.The procession would go by, down the hill into the wintry afternoon with its faint foggy smell that gripped your throat if you were out in it. It was the smell of coal fires and winter . . . I would wait. Then faintly the bugle would sound, final and sad, the lamenting never-coming-back notes of the Last Post. It seemed to me a dark, smoky, red slash of sound against the quiet grey of the London winter evening coming down.

Typically Betts recalls that it was the Bebbs’ scurfy eyelids, rather than anything else about them, that attracted the attention of her 10-year-old self, and it is details like this that make People Who Say Goodbye such a joy – ‘the most amusing book of childhood memories I can remember reading’ as Graham Greene described it. Somehow the older woman managed to get right inside the head of the little girl whose ambition from the age of 10 was to write an encyclopaedia, but who realized when she was 12 that ‘the whole idea was absurd. Childish.’ The book is an irresistible tragi comedy – the mysterious actions and reactions of the adult world brilliantly recreated through the eyes of an observant and humorous child. What became of Phyllis after St Paul’s? I do not know. I only know that many decades later sheer chance drew out of her one of the most deliciously funny and truthful books about childhood that I have yet come across.‘What’s it like at the Bebbs’?’ my mother asked me.

‘It’s not bad . . . Most of them have scurfy eyelids where the lashes come through.’ ‘Most of what?’ ‘Most of the Bebbs.’ ‘Must be getting the wrong diet. Probably not enough greens or animal fat. You must take them some lettuces, there are more than we can eat in the garden.’

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 29 © Hazel Wood 2011

About the contributor

Hazel Wood grew up in an unconventional household, worked in Fleet Street, and is now co-editor of Slightly Foxed.