An Edwardian villa in Brighton, 1957

It is cold and chaotic because we have only just moved in. Home from school, I go into my bedroom, turn on my little white portable radio and flop down on my bed. The date must be 10 or 11 May, for that is when Jean Rhys’s play based on her novel Good Morning, Midnight was first broadcast on the BBC Third Programme. I have never heard of Jean Rhys but, as I listen to the play, I become involved. I feel instant kinship with the protagonist, which is odd because she is a sad, rather desperate, ageing woman alone in Paris and I am a lively, gregarious schoolgirl. I decide that what this writer has captured so brilliantly is mood. The play evokes a sort of melancholy which I recognize as existing in everyone to a greater or lesser degree. GMM becomes a shorthand symbol in my diary not only for this mood but also for the ability to express it. I have wanted to be a writer since the age of 10: now I am determined. I try in vain to find out more about the writer of the play and discover a story in a very old Penguin New Writing. Then someone tells me she is dead.

Good Morning, Midnight is in fact the fourth in a series of novels that draw largely on Jean Rhys’s own life. Sasha Jansen is a lonely, ageing alcoholic who, at the instigation of a worried friend, goes to spend a recuperative fortnight in Paris, where she had lived during her brief marriage. Now she wanders the streets, ‘remembering this, remembering that’. She has been so damaged by men that when happiness is within her grasp she is unable to prevent herself seeking revenge with a futile gesture of self-destruction.

Charing Cross Road, London, 1967

I am now a young woman. I have been living it up in Paris. I still intend to write, but life is full of fun and no GMM symbol has appeare

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAn Edwardian villa in Brighton, 1957 It is cold and chaotic because we have only just moved in. Home from school, I go into my bedroom, turn on my little white portable radio and flop down on my bed. The date must be 10 or 11 May, for that is when Jean Rhys’s play based on her novel Good Morning, Midnight was first broadcast on the BBC Third Programme. I have never heard of Jean Rhys but, as I listen to the play, I become involved. I feel instant kinship with the protagonist, which is odd because she is a sad, rather desperate, ageing woman alone in Paris and I am a lively, gregarious schoolgirl. I decide that what this writer has captured so brilliantly is mood. The play evokes a sort of melancholy which I recognize as existing in everyone to a greater or lesser degree. GMM becomes a shorthand symbol in my diary not only for this mood but also for the ability to express it. I have wanted to be a writer since the age of 10: now I am determined. I try in vain to find out more about the writer of the play and discover a story in a very old Penguin New Writing. Then someone tells me she is dead.

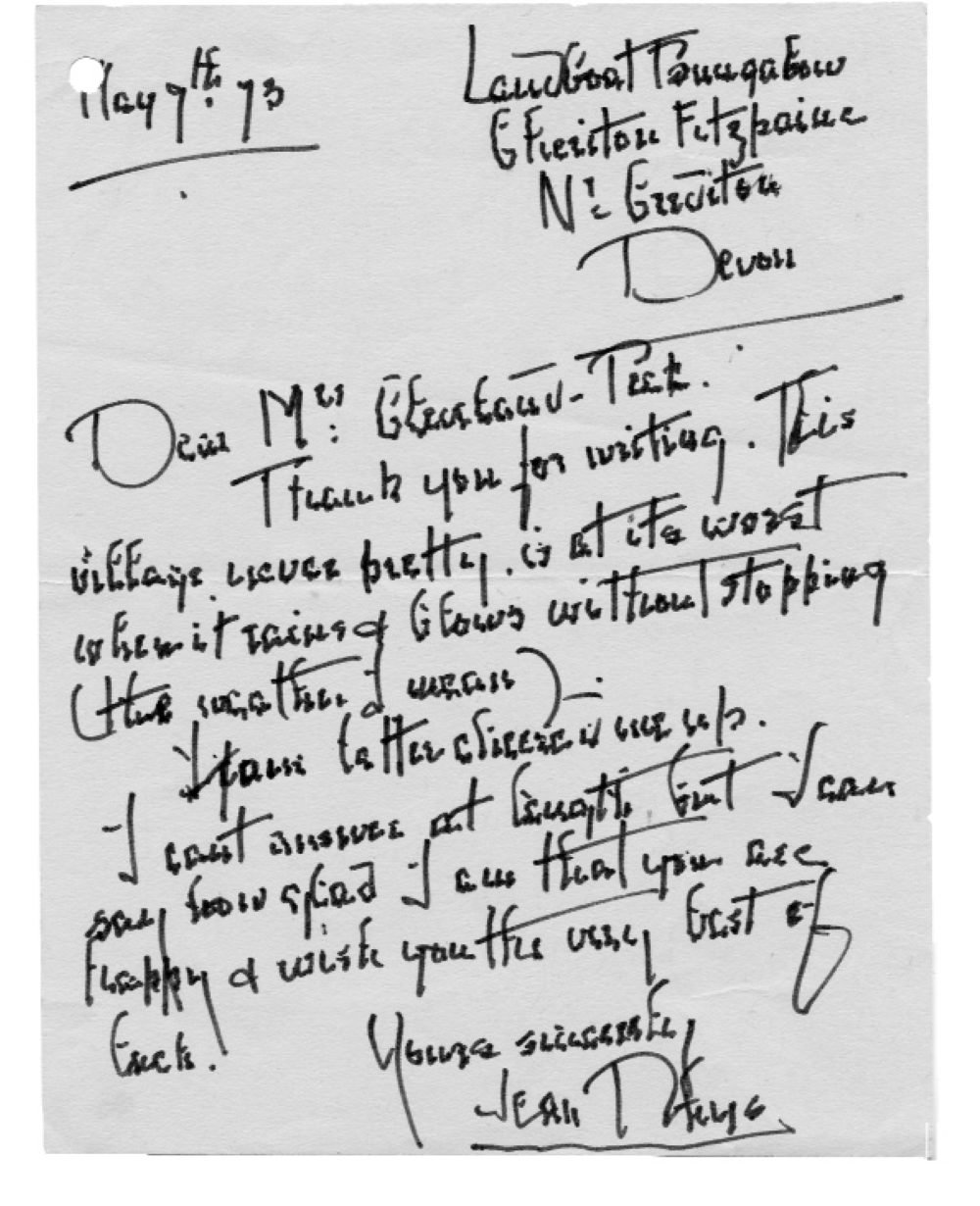

Good Morning, Midnight is in fact the fourth in a series of novels that draw largely on Jean Rhys’s own life. Sasha Jansen is a lonely, ageing alcoholic who, at the instigation of a worried friend, goes to spend a recuperative fortnight in Paris, where she had lived during her brief marriage. Now she wanders the streets, ‘remembering this, remembering that’. She has been so damaged by men that when happiness is within her grasp she is unable to prevent herself seeking revenge with a futile gesture of self-destruction. Charing Cross Road, London, 1967 I am now a young woman. I have been living it up in Paris. I still intend to write, but life is full of fun and no GMM symbol has appeared in my diary for a long time. Today I am wearing a new suit, pale grey and beautifully cut. I feel happy to be alive. Suddenly I see a window display of books by Jean Rhys. My feelings are mixed: delight at learning that she is alive after all and that I will be able to read more of her, but also a vague regret that my secret writer is now public property. The books, however, do not disappoint me. Voyage in the Dark, set in 1914, tells the story of Anna, a 19-year-old Creole from the West Indies who is now a chorus girl in London and whose experiences mirror Jean’s own. Once again I feel a sense of recognition, although it would be hard to say of what exactly. Anna is innocent and childlike and soon falls in love with a man she picks up. We know he will never marry her, and when he finally tires of her she drifts into a life of prostitution and finally suffers an abortion. The sections in which Anna slips back to the warmth of her Caribbean childhood are pure poetry, evoking the scents and sounds of a longed-for past; while the life of chorus girls in cold and bleak England – their language, their jokes, snatches of songs, the atmosphere of their dingy rooms – is captured perfectly. Jean Rhys apparently cut her texts again and again until the words expressed the essentials of the experiences she wanted to portray. I recognize this as a supreme skill, as something I desperately want to be able to do myself. Two other books, Quartet and After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, deal with the lives of women who are very similar to Sasha and Anna. Ashurstwood, a village in Sussex, 1970s I live in the country, happily married with three tiny children. I still want to write but life is . . . full. Eventually my husband fixes a little attic room reached by a staircase so steep that no dog or child can follow, and I creep up there to write. But nothing I write satisfies me. It is here (for I still use my attic room) that I write my first letter to Jean Rhys. I have read all the books, and Wide Sargasso Sea, published in 1966, has brought Jean international recognition. The book is inspired by Mr Rochester’s mad wife in Jane Eyre. Antoinette Cosway, the daughter of a Creole family, lives in the lush and sensual West Indies at a time when relations between ex-slaves and the whites are tense. Their house is burned down and her mother goes mad and dies. Shortly afterwards Antoinette is married off to an Englishman glad of her dowry. She soon realizes that he does not love her and eventually crosses from sadness to madness. The end of the story, of course, is in another book. In a way the psychological mysteries of all Jean Rhys’s preceding female characters are explained by the background they share with Antoinette. Here the sense of alienation and loneliness is conveyed with such wonderful imagery and in such lyrical language that it is little wonder Wide Sargasso Sea is hailed as Jean Rhys’s masterpiece and that her name now features in standard reference books. Not only does she reply to my letter, she also tells me that it has cheered her up. She does say that she cannot answer at length but she says nothing to deter me from writing again. Thus begins a sporadic correspondence throughout which her letters, often no more than short messages wishing me luck, keep my hopes of writing alive. Cheriton Fitzpaine, Devon, 13 August 1978 Tomorrow I am to visit Jean. Several letters have gone back and forth planning this meeting and now I am here. One of the villagers puts me up for the night and over breakfast she and her husband tell me in conspiratorial voices that in the village Jean is known as Mrs Hamer (she had married her third husband, Max Hamer, in 1947) and is generally thought of as a witch. I am shocked and tell them that she is one of our greatest writers. They counter by saying that she lives in the ‘uneducated’ (their term) part of the village. I sense antipathy and decide to go out for a walk. Jean has often told me how she dislikes this village and I begin to see why. As I stroll around, the thing that strikes me is how time, at home an inadequate struggle of a thing, is here so heavy and languid. I decide to locate Jean’s house so that I will be on time this afternoon. I know it is called Landboat Bungalow, a name I enjoyed writing on the envelopes of my letters to her, imagining a cottage moored in an ocean of ripening corn. It turns out to be in a mean row of rural dwellings, one of which (not Jean’s) is quite derelict. I look beyond; Devon is beautiful. This, however, is no picture-book scene – it is rural poverty, stinging nettles and cold, restless rain. At the appointed hour my heart is beating fast as I push open the green metal gate. I am greeted by Jean’s daughter, Maryvonne. ‘She is very like her,’ I think, never having seen ‘her’. Then I am shown into the sitting-room and I am seeing her. She is tiny, propped up in an armchair, face elaborately made-up, eyes big and blue. She must have been beautiful, but now she is gnarled, bent, reptilian and very, very old. I glance around. The house has been newly decorated and there are books, rugs and some colourful paintings, but there is no escaping the fact that Jean does not live in any great style. This is not how I imagined her surroundings. She speaks and her voice is another surprise; what the French call une voix cassée with, underneath, the strange West Indian accent she never lost and which cost her her career as an actress – ‘You and your drawly voice’. Maryvonne takes the bottle of champagne I have brought. She doesn’t want to open it but Jean persuades her, saying champagne always does you good. Maryvonne then leaves us and we talk about Paris. Jean sounds exactly like a character from her books. ‘At first we lived somewhere behind the Galeries Lafayette, rue Lamartine I think it was . . .’ She and her first husband, the Dutchman John Lenglet, were always hard-up. Then they moved to Montparnasse. ‘Café de la Rotonde, Le Dôme – they say the old café life has ended but I can’t believe it somehow . . .’ She says there was something about the whole atmosphere of Paris that made her want to write. ‘You just breathed it in . . . In Paris art matters, it is really considered important, but in London only money matters.’ Then she goes on to say that in London she never read anything, though as a child she had read a lot. But in Paris she found she learned to read French quite quickly and there was something about French writing that she liked. It didn’t go on and on like so many English books, it seemed to the point. I ask her which books and she says Colette and then adds, ‘Later I read Hemingway who had a certain influence on me.’ We drift on to other subjects – Dominica, the cold, how she tries to winter somewhere else, Venice or London. Maryvonne comes back with Jean’s nurse. They say that Jean must not get too tired but Jean starts talking about some photographs that have been taken of her and which she hates. She points to some copies of Vogue and says that writing has not brought her nearly as much excitement as being beautiful. I can see how dreadfully this matters to her: how she hates being old and frail. We drink the last of the champagne and I say goodbye. She looks vague and tired. I thank her and she says she doesn’t know what I’m thanking her for. In fact I am thanking her for being the sort of writer who makes a reader want to write.*

Jean died in May 1979. Although I prefer to remember just our one pleasant afternoon with champagne, I have since read about Jean’s life in many books, including Carole Angier’s masterly biography. Sometimes I recognize her clearly, sometimes she is a hideous stranger. Parts of her life were hard: betrayal, abortions, poverty, a baby dead, starvation, a husband in prison, a daughter abandoned, homelessness, loneliness, incompetence, rages, drunkenness . . . She once said that she would have preferred a life of only average happiness to the greatest literary triumphs, but she didn’t have a choice – she was a writer. The experiences of her life were her raw material and she devoted the best of herself to turning them into literature. That’s what writers do. And that is what communicated itself to me on that evening long ago when, as a schoolgirl, I first heard Good Morning, Midnight on the radio.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 4 © Patricia Cleveland-Peck 2004

About the contributor

Patricia Cleveland-Peck did end up as a professional writer and is the author of children’s books, adult non-fiction books and two radio plays. Her first stage play was performed at York in May 2004.