Some months ago I became a British citizen. This wasn’t such a stretch for a native of the States, but it put me in mind of other transplanted people and I have been rereading some old favourites to celebrate. Perversely, the most resonant thing I’ve read isn’t British at all: a tale written in French by a Belgian who became American and settled on an island near my family’s summer home in the northern state of Maine. It is a quiet piece of literary grisaille called Un homme obscur, ‘An Obscure Man’.

The author, Marguerite Yourcenar, is immortal in the Francophone world and in America, but she is oddly under-appreciated in Britain. She became peculiarly immortelle in 1980 as the first woman to be elected to the Académie française. Her vaguely oriental-sounding nom-de-plume is a rearrangement of the letters of her name at birth – de Crayencour. Born an aristocrat in Brussels in 1903, she became a plain American citizen in 1951 and settled permanently in a remote part of Maine, near the uttermost end of New England. Her home was a white cottage called La Petite Plaisance above Seal Cove, on the island she referred to throughout her life as L’Île des Monts Déserts. To the natives this is Mount Desert Island, variously pronounced like the dry empty place or the last course at dinner.

Also at this time Yourcenar published the work that has become her most famous, Les Mémoires d’Hadrien, an historical novel delving into the mind of the Roman emperor Hadrian (see Slightly Foxed, No. 2). In 1968 came a complementary novel, much darker in tone and thus fittingly entitled L’Oeuvre au noir, and in English The Abyss; set in sixteenth-century Europe, it comprises a long meditation on the abuses of power over intellect and the irrepressible power of the intellect to endure. In a much smaller novella begun in 1934, Yourcenar wrote about a man similarly buffeted by the wind

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inSome months ago I became a British citizen. This wasn’t such a stretch for a native of the States, but it put me in mind of other transplanted people and I have been rereading some old favourites to celebrate. Perversely, the most resonant thing I’ve read isn’t British at all: a tale written in French by a Belgian who became American and settled on an island near my family’s summer home in the northern state of Maine. It is a quiet piece of literary grisaille called Un homme obscur, ‘An Obscure Man’.

The author, Marguerite Yourcenar, is immortal in the Francophone world and in America, but she is oddly under-appreciated in Britain. She became peculiarly immortelle in 1980 as the first woman to be elected to the Académie française. Her vaguely oriental-sounding nom-de-plume is a rearrangement of the letters of her name at birth – de Crayencour. Born an aristocrat in Brussels in 1903, she became a plain American citizen in 1951 and settled permanently in a remote part of Maine, near the uttermost end of New England. Her home was a white cottage called La Petite Plaisance above Seal Cove, on the island she referred to throughout her life as L’Île des Monts Déserts. To the natives this is Mount Desert Island, variously pronounced like the dry empty place or the last course at dinner. Also at this time Yourcenar published the work that has become her most famous, Les Mémoires d’Hadrien, an historical novel delving into the mind of the Roman emperor Hadrian (see Slightly Foxed, No. 2). In 1968 came a complementary novel, much darker in tone and thus fittingly entitled L’Oeuvre au noir, and in English The Abyss; set in sixteenth-century Europe, it comprises a long meditation on the abuses of power over intellect and the irrepressible power of the intellect to endure. In a much smaller novella begun in 1934, Yourcenar wrote about a man similarly buffeted by the winds of his time, though in this instance a man of no distinction: un homme obscur. This young nobody named Nathanaël simply ‘lets life flow over him’. His tale – watery, dreamy and set on islands like Yourcenar’s home and mine – forms part of a triptych called Comme l’eau qui coule, or Two Lives and a Dream. Nathanaël is born in England, into the Dutch ship-building community of early seventeenth-century Greenwich. At 15, he stows away on a ship, and after various Caribbean adventures – sexual and piratical and generally maturing – he finds himself bound for the north-east of North America. Yourcenar’s descriptions of the coast of Maine are remarkably evocative, and capture a place at once close in my mind and frustratingly distant in space:The sea that summer was almost always calm and, in certain latitudes, virtually empty. The farther north they went, the more sultry humidity gave way to fresh breezes; the transparent sky became milky whenever a thin layer of mist covered it; on the banks of the mainland or of the islands (it was not always easy to tell one from the other), impenetrable forest descended to the sea shore.The ship eventually lands on an unnamed island which, it is clear to me, is Mount Desert Island, whose outline and appearance are as sharp in my mind as on any map. ‘Steep and rocky, covered in its low areas with pines and oaks, its six or seven mountains could be seen from afar . . . An arm of the sea reached far into the island from the south, forming a vast natural port marvellously sheltered from the wind.’ This can only be Soame Sound, a unique arm of water, the only proper fjord on the American Atlantic seaboard, very near the place where Yourcenar herself came to live. Later, Nathanaël’s ship is wrecked on another small island which he learns is called the Île Perdue. This is in fact the name given on Samuel de Champlain’s 1607 map of Penobscot Bay to the group of islands that includes my own home. It is indescribably exciting and poignant to be so far away from a place so obscure, and yet so easily brought back by this book. The feeling isn’t like being born in London and reading Dickens in Maine; that can happen any day, and is entirely different from this unlikely recollection. Yourcenar fled the distracting salons of Europe to write in quietude, the very opposite of someone like Balzac. I swapped my Île Perdue for this cosmopolitan island where I can make a living, but from the rich clarity of Yourcenar’s tale I am acutely aware of what I have left behind. For a time, Nathanaël lives among the island’s precarious settlement of Europeans. From a sparse archaeological record we know that such people did somehow survive on the islands of Maine, at least for a few years at the start of the 1600s, living out their obscure lives. Yourcenar deftly evokes their rooted rootlessness, a strange state I know well – happy here, but missing there, and no longer sure what’s where. Nathanaël falls into a sort of love with a girl called Foy. Their attraction is depicted almost as the natural consequence of spring emerging on the island, and is more sensual and corporeal than emotional. High is the irony, then, when Foy’s body begins to decay with tuberculosis, and she dies in October. ‘It was at the time when the forests, scorched by the summer sun, produced great masses of reds, dark purples, and golden yellows. Nathanaël told himself that the queens for whom they draped the churches of London had far less beautiful obsequies than these.’ Maine’s early autumn landscape is indeed coruscatingly colourful, but somehow also mournful – a swansong, a brilliant pall. And if Christopher Wren could have seen the cathedral woods of interlocking perpendicular pines, monuments of an ancient and enduring obscurity, he would have looked around himself in wonder. With Foy’s death, Nathanaël quickly comes to loathe the Île Perdue; he jumps aboard a passing ship and leaves. After several years in which he wanders back through England and Holland, through dank Northern European winters, he too begins to succumb to tuberculosis. To quarantine himself, he becomes the gamekeeper on an otherwise uninhabited Friesian island on the northern coast of Holland, an island so flat and windswept and treeless it is barely more than a sandbar:

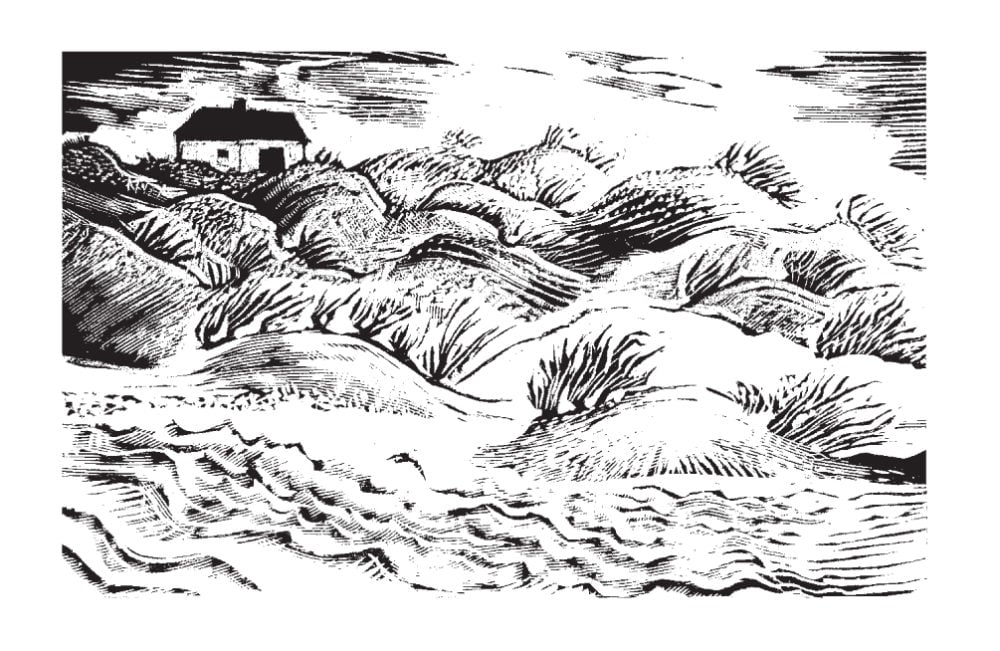

Between the house and the sea, which could only be glimpsed, the dunes formed enormous waves, moulded, it seemed, from the actual waves that had sculpted them. They were stable, if anything can be; yet felt as if they moved invisibly, shrinking here and expanding there. A sort of mist of sand raced and scraped across them, chased by the same wind which scatters the mist from the waves. Tufts of isolated dune grass trembled gently in the strong wind. No, it wasn’t the Île Perdue, which had been composed of rocks, shingle, barrens, and trees attached to the rocks by their roots, as if with great clutching hands on which the veins stood out.The island in Maine suddenly re-intrudes into the text, much more strongly than a mere memory: it has physical force and strength – those veined hands, clutching rocks. This happens to me: I sometimes feel the loss of home quite forcefully, in the insufficient similarity of this great island to my own tiny one. It can be a bleak, reeling sensation, a palpable displacement which I expect Yourcenar herself knew well, too. Perhaps to ward off this feeling, or to placate the gods who send it, she sacrifices Nathanaël by setting him utterly adrift. She places him on an island which is barely an island, more sea than sand, shifting and unstable – with his life ebbing out of him like a tide. ‘Here, everything was undulating or flat, shifting or liquid, pale yellow or pale green’ – a stark contrast to the vivid colours of Maine arrayed for Foy’s funeral, on an island which, though lost, was as solid a place as Nathanaël ever lived in. But now he is adrift: ‘the clouds themselves heaved about like sails. He had never felt himself at the centre of such tremulousness.’ In the end, Nathanaël does not fare well. I think I’m doing substantially better myself, integrated as I am as a subject of Her Majesty the Queen. I passed that daft citizenship test, and swore to defend the realm in time of war or other adversity, and was even awarded a solid glass paperweight at my swearing-in ceremony by a jolly chap with a South African accent and a Goanese name. After a celebratory British breakfast with my mates in a café – HP sauce on the bacon, Heinz 57 on the eggs – I felt no different, certainly not significant. But also not adrift. Yourcenar reminds me that my Île Perdue can never be lost, nor entirely displaced by Britain. And I, un homme obscur, am more or less at home in either place.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 21 © Pegram Harrison 2009

About the contributor

Pegram Harrison returns to Maine whenever he can, and otherwise lives in an odd angle of this isle called Islington.