I was born on 26 January 1962 in a small upstairs bedroom at 8 Fairview Road, Norbury, South London. Towards the end of that year the world held its collective breath as, courtesy of the Cuban Missile Crisis, it teetered on the brink of nuclear oblivion. I have always wondered if the two events were connected. The year 1962 also saw the first publication of Betty Hope’s Survive with Me by R.G.G. Price, illustrated by Ionicus. I found my copy earlier this year in the local Oxfam shop, lurking between a suntan-oiled copy of The Da Vinci Code and an early example of Jamie Oliver’s literary oeuvre entitled, I think, It’s Beans on Toast, Mate. Mr Price’s book was clearly lost. Equally clearly the Oxfam shop needed to sort out how it arranged its books. I’m all in favour of serendipity, but if books in Oxfam shops are being shelved willy-nilly, surely the country’s in a far worse state than even that nice Mr Cameron would have us believe.

Struck by the coincidence of our birth years, I picked up Mr Price’s book, and I am glad that I did. One glance at the cover and I knew that this was going to be a subversive gem. On the left is an illustration of Betty Hope, a cheery woman in her late forties. In her arms is a collection of things that might prove useful in a domestic emergency – a first-aid box, a kettle, a bag of groceries, a pair of shoes with sensible heels, a hot-water bottle and a Union Jack on a pole. On the right, illustrating just what sort of domestic emergency we’re dealing with, is a meticulously cross-hatched picture of an atomic mushroom cloud.

Inside the book we are soon introduced to Betty and her family. Her husband Jim is a costing clerk at Universal Valve and is ‘keen on hobbies’. Sylvia, her daughter, is 16 and ‘very fond of dancing and riding pillion’. Andy is a year older and works in a garage, and Tony is still at school. Tony came seventeenth in his class last term, ‘hel

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI was born on 26 January 1962 in a small upstairs bedroom at 8 Fairview Road, Norbury, South London. Towards the end of that year the world held its collective breath as, courtesy of the Cuban Missile Crisis, it teetered on the brink of nuclear oblivion. I have always wondered if the two events were connected. The year 1962 also saw the first publication of Betty Hope’s Survive with Me by R.G.G. Price, illustrated by Ionicus. I found my copy earlier this year in the local Oxfam shop, lurking between a suntan-oiled copy of The Da Vinci Code and an early example of Jamie Oliver’s literary oeuvre entitled, I think, It’s Beans on Toast, Mate. Mr Price’s book was clearly lost. Equally clearly the Oxfam shop needed to sort out how it arranged its books. I’m all in favour of serendipity, but if books in Oxfam shops are being shelved willy-nilly, surely the country’s in a far worse state than even that nice Mr Cameron would have us believe.

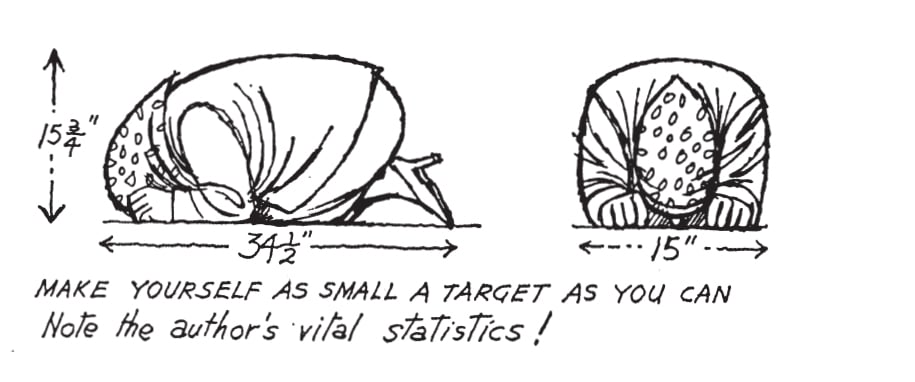

Struck by the coincidence of our birth years, I picked up Mr Price’s book, and I am glad that I did. One glance at the cover and I knew that this was going to be a subversive gem. On the left is an illustration of Betty Hope, a cheery woman in her late forties. In her arms is a collection of things that might prove useful in a domestic emergency – a first-aid box, a kettle, a bag of groceries, a pair of shoes with sensible heels, a hot-water bottle and a Union Jack on a pole. On the right, illustrating just what sort of domestic emergency we’re dealing with, is a meticulously cross-hatched picture of an atomic mushroom cloud. Inside the book we are soon introduced to Betty and her family. Her husband Jim is a costing clerk at Universal Valve and is ‘keen on hobbies’. Sylvia, her daughter, is 16 and ‘very fond of dancing and riding pillion’. Andy is a year older and works in a garage, and Tony is still at school. Tony came seventeenth in his class last term, ‘helped by good marks for welding’. Betty herself is the matriarch of the happy clan and a County Champion at hat trimming. On top of all this they live in ‘a very nice part’ with good bus services and, as Betty herself puts it, ‘there is nothing we would rather do than go on just as we are’. One fine summer evening as the family sit in the garden, Betty says how lucky they are to be alive at such a blessed time. The conversation then turns to recent wonderful inventions and advances, with votes being cast for plastics, the telly, statistics, and gas ovens in crematoriums, before young Tony pipes up with ‘What about bombs?’ A brief romp through the history of bombs ensues and ends up with Sylvia asking whether ‘we didn’t think the idea of delivering the old H-bomb as the warhead of a rocket wasn’t dreamville’. Safe and snug in their garden, with no cloud on the horizon, and the scent of tobacco plants and stocks in the air, the Hopes all agreed that it was indeed wonderful. The rest of the book deals with just what to do when ‘The Bomb’ does go off. Given such an unfortunate turn of events, ‘We are all very keen on winning through,’ says Betty. Well, who wouldn’t be? First advice concerns the ‘hidey-hole’. Betty chooses the diningroom as this is decorated in pastel shades ‘which will be restful’. It also contains a big table which they can all sleep under. Tips then follow on heating, cooking, hygiene, the whitewashing of windows, and the use of sandbags and their decoration. A whole chapter is devoted to the etiquette of dress within the shelter and ends with an illustration of an anti-fallout bowler hat (obtainable from ‘better class shops in London’s West End’). What to do to pass the time in the shelter is another major concern. But as Betty so admirably has it, ‘One thing we don’t intend is to get the blues.’ On one wall she’s arranged red, white and blue paper butterflies that spell out, ‘There’ll always be an England’. Patience, rummy, bagatelle and Twenty Questions all find favour, as does singing. But, unfortunately, ‘the room is too small to show holiday films on the wall’. However, it is not until Chapter 7 that the full horror of atomic war is addressed in terms that would move any member of the British public. Its simple title says it all. ‘Are we to abandon our pets?’ The year 1962 marked the height of the Cold War. As the year went on, however, things started to get much, much warmer. The Cuban Missile Crisis was triggered by the US discovering that the Russians were siting missiles on Cuba that were capable of carrying atomic warheads to the American mainland. What’s often forgotten is that this in itself was probably a reaction to the positioning of US missiles in Turkey that could reach the USSR. In short it was the year when Armageddon was a real possibility. Britain, like the rest of the world, could do little more than watch. And worry. Unless, of course you were R. G. G. Price. Then you could write a book that not only laughed in the face of the impending apocalypse, but did so with charm and wit. The illustrations by Ionicus complement the writing perfectly. What little information I can glean on Mr Price reveals him to have been a regular writer for Punch, best remembered for his 1957 book A History of Punch. Ionicus was the pseudonym of Joshua Armitage who himself contributed cartoons to Punch for forty years and produced, among other things, 58 cover illustrations for the Penguin series of P. G. Wodehouse. Apparently he chose the name Ionicus because the very first cartoon he had had published had featured a concert hall with Ionic columns. That both Mr Price and Ionicus could respond to the potential atomic googly of a mushroom cloud in the shrubbery with such a straight bat may well be in part explained by the fact that 1962 was only seventeen years after the end of the Second World War. Death and destruction on a massive scale were not just some hypothetical possibility, or a dim and distant memory, but a very real part of a commonly experienced, and survived, past. And Hiroshima and Nagasaki weren’t just names from history books. To put this all into some kind of temporal perspective, count back seventeen years from now and you’re in the days when Nintendo launched the Gameboy, John Major set up his cones hotline, and Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ topped the charts. So seventeen years isn’t that long ago. The point that I’m trying, somewhat clumsily, to make is that when you’ve already lived through the world being torn apart by war, you’re more likely to step back from the prospect of oblivion and take it all with a pinch of salt. And a large helping of satire. Which is not to say that Mr Price shied away from the grim realities of what he was writing about; it’s just that he wrote about them in such a gentle and helpful way that even the most rabid of Cold War warriors and the most paranoid of Cold War worriers would surely smile. Chapter 13 is entitled ‘Some Things to Watch out for’:If you should happen to be out of doors when the bomb goes off, and four minutes is not very much time to get out of a butter queue and back home, you may notice it getting hotter. This is heat flash. It decreases very quickly with the distance from the centre of the explosion. TURN YOUR BACK. The bright light can make eyes sore and the less exposed skin there is to blister the better.A little later in the chapter comes a sweet little drawing of how to make yourself as small a target as possible to minimize the effects of ‘rays’. Accompanying the picture is the advice, ‘Dark glasses will not stop rays, though, of course, if you feel they suit you wear them by all means.’ If only Mr Price and Ionicus were around today. Then we might be able to put our current paranoia about terrorism into perspective. Instead, the only publication that deals with the problems that may arise from ‘The War on Terror’ is one put out by the government. This is the 22-page publication, entitled ‘Preparing for Emergencies’, which was sent to ‘every household in the country’ a while ago. For some reason I didn’t get one. I took that as a hint. But I rang up and ordered a copy anyway. It is a prettily designed little leaflet in which, so as not to alarm you too unduly, key words and phrases are highlighted in blue type. The only exception to this is on p. 9 where a murky pink tone is used to pick out the words ‘keep calm’. Throughout, reassuringly round-cornered boxes contain sections of advice on ‘Bombs’ , ‘Burns’, ‘Bleeding’ and ‘Broken Bones’. There are also very useful hints on what to do in the event of a ‘chemical, biological or radiological (CBR) incident’. Apparently the first thing you should do is ‘Move away from the immediate source of danger’. Which is definitely worth knowing. However there is no advice on what to do with your pets. The introduction to the leaflet features a quote from a lady who holds the position of Chief Executive of the Emergency Planning Society. Unfortunately her name is Debbie. Which to my mind, and you can call me an unreconstructed Debbie-ist if you like, somewhat undermines the seriousness of the message. But the very existence of an Emergency Planning Society is reassuring. As is the fact that ‘The material used in this publication is constituted from 75% post-consumer waste and 25% virgin fibre’. Having said all this, the big drawback of the leaflet is that it is a leaflet. Hold it in your hands and it is as insubstantial as a random selection of pizza flyers stapled together. Unfortunately this means that it is all too easy to misplace or inadvertently discard. Or even advertently discard. Betty Hope’s Survive with Me, however, is an altogether more substantial bill of fare. And, I would argue, a far more useful one. Even in the current crisis. After all, surely the best way to combat paranoia is with perspective – and maybe just a dusting of parody. The very last page in Survive with Me features an illustration of an atomic mushroom cloud with the Hope family sitting cheerily atop it clutching a Union Jack. Underneath this is the caption, ‘Above all, keep smiling!’ Oh Mr Price, where are you now that your country really needs you?

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 13 © Rohan Candappa 2007

About the contributor

Having survived the Cuban missile crisis rohan candappa went on to write a satire on the build-up to the second Gulf war entitled The Curious Incident of the WMD in Iraq and has recently published Viva Cha!, the definitive guide to the parallels between the lives of Prince Charles and Che Guevera.