Some bird books, the ones you take with you across mountains, into bogs or through jungles, are small in size, compact and easy to stuff into backpack or pocket, offering ready reference in all locations and in all weathers. C. A. Gibson-Hill’s British Sea Birds is not of that kind. A large hardback, too cumbersome to take into the field, intended for the shelf in library or study, it is a work of education and of celebration. It was written by a man who loved birds for others who shared his passion, to enlighten and delight; and it merits the highest compliment one can pay to such a book – it makes one want to go out and see the birds for oneself, to get to know them as he did.

I found British Sea Birds in a second-hand bookshop in York and, enchanted by it, tried to find out something about the author, whose name was entirely unfamiliar to me. A little research uncovered something of the remarkable history of Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill. A doctor by training, a naturalist and ornithologist by passionate inclination, he spent most of his life in Singapore working as a zoologist and museum curator; but he was also an able historian, a gifted photographer and a tireless traveller and writer – a man who was, as Singapore’s Straits Times said in an appreciation published after his death, ‘outstanding in many fields’.

Gibson-Hill, who was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1911, qualified as a doctor in 1938, and immediately sought a medical post in some remote place where he could devote himself to natural history. He managed to find such a position on tiny Christmas Island in the eastern Indian Ocean, and arrived there in the summer of 1939, having travelled largely overland, via Afghanistan, India and Indochina, on foot or by bullock-cart. Barred from active service in the Second World War by his acute short-sightedness, Gibson-Hill remained in the East and was in Singapore with his wife Margaret (also a doctor) when the

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inSome bird books, the ones you take with you across mountains, into bogs or through jungles, are small in size, compact and easy to stuff into backpack or pocket, offering ready reference in all locations and in all weathers. C. A. Gibson-Hill’s British Sea Birds is not of that kind. A large hardback, too cumbersome to take into the field, intended for the shelf in library or study, it is a work of education and of celebration. It was written by a man who loved birds for others who shared his passion, to enlighten and delight; and it merits the highest compliment one can pay to such a book – it makes one want to go out and see the birds for oneself, to get to know them as he did.

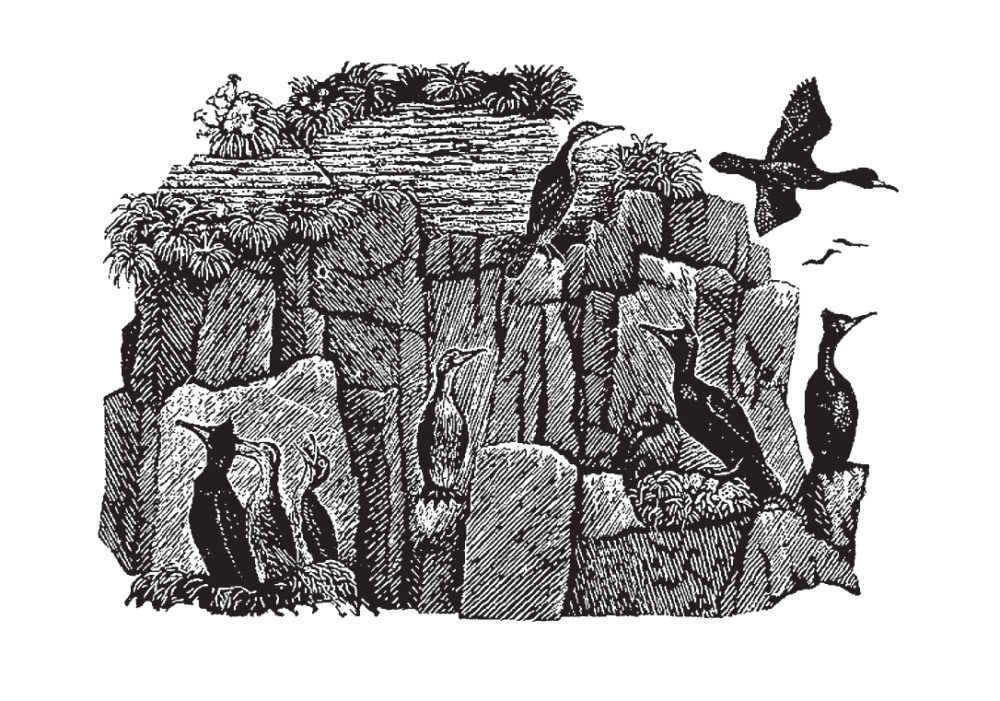

I found British Sea Birds in a second-hand bookshop in York and, enchanted by it, tried to find out something about the author, whose name was entirely unfamiliar to me. A little research uncovered something of the remarkable history of Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill. A doctor by training, a naturalist and ornithologist by passionate inclination, he spent most of his life in Singapore working as a zoologist and museum curator; but he was also an able historian, a gifted photographer and a tireless traveller and writer – a man who was, as Singapore’s Straits Times said in an appreciation published after his death, ‘outstanding in many fields’. Gibson-Hill, who was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1911, qualified as a doctor in 1938, and immediately sought a medical post in some remote place where he could devote himself to natural history. He managed to find such a position on tiny Christmas Island in the eastern Indian Ocean, and arrived there in the summer of 1939, having travelled largely overland, via Afghanistan, India and Indochina, on foot or by bullock-cart. Barred from active service in the Second World War by his acute short-sightedness, Gibson-Hill remained in the East and was in Singapore with his wife Margaret (also a doctor) when the city fell to the Japanese in February 1942. Margaret escaped and returned to Britain, but Gibson-Hill, who had been acting curator of the Raffles Museum as the Japanese closed in, was interned with other civilians in Changi Jail. During his three and a half years of confinement Gibson-Hill wrote, lectured, organized entertainments (until the Japanese put a stop to them), ran the prison kitchen, and made plans for what he would do after the war. Among those plans was the writing of two books on British marine birds: the birds of the sea, and the birds of the coast. It was that project that he pursued, a free man once more, through the summer of 1946. (He had reached Britain following his release by travelling from Singapore to Cairo, then going on to Durban to join a whaler which took him to the South Atlantic – where he paused to study the birds of South Georgia – before finally completing his journey as medical officer on an oil tanker.) Gibson-Hill’s British Sea Birds appeared in 1947 (its companion, Birds of the Coast, followed two years later). It is a beautiful hardback book, adorned with a colour photograph of a Puffin on the cover which is repeated as a frontispiece. Its 144 pages contain what Gibson-Hill calls ‘short biographies’ of twenty-four sea birds that regularly breed in the British Isles. Some have biographies of their own (‘The Gannet’, ‘The Fulmar’), others are gathered into groups (‘The Scavenging Gulls’, ‘The Guillemots’). The author was very much a field naturalist, and accordingly British Sea Birds takes you where its author went, out among the birds, into their world. Gibson-Hill’s birds, captured in his fresh, lucid prose and exquisite photographs, are not dead specimens, anatomized by a detached scientific gaze. They fly free from every page, carrying the salt breeze and the sound of the waves with them. British Sea Birds is a practical field guide, giving all necessary details of appearance and behaviour, but Gibson-Hill goes further, capturing in vivid, well-chosen details the elusive character of the birds: the Puffin’s ‘nautical roll’, the ‘strained, rapacious set’ of the head of the Herring Gull, the ‘erratic wandering course’ followed by Storm Petrels across the face of the waves, ‘like large-winged butterflies or small bats’. His pen-portrait of the Kittiwake, the ‘smallest, most marine and most attractive’ of the British gulls, is affectionate and precise:It has roughly the shape and colouring of a small Herring Gull, but it is softer and gentler in its lines. Sitting birds have a delicate, demure appearance that is quite lacking in the larger species. Even in repose the Herring Gull has the look of a brigand, while a nesting Kittiwake might be a well-pleased young woman, newly married.

By way of contrast, the Great Black-backed Gull has ‘the aloofness and easy carriage of an individual always sure of getting its own way’. This proud and rapacious bird, Gibson-Hill writes, ‘makes considerable slaughter among the sea birds round it, but it kills, not half apologetically as the smaller species seem to, but as though all its actions are covered by a divine mandate’.

The man who wrote those words had lived through the siege and capitulation of Singapore and had only lately returned to a warbattered Britain from captivity at the hands of the Japanese. Unsurprisingly, British Sea Birds is not free from the shadows cast by war. When Great Skuas are disturbed, Gibson-Hill writes, they respond with ‘a systematic attack’, swooping ‘straight at one’s head from a considerable height’:

There is little doubt that they aim at frightening the intruder rather than injuring him; the effect is like that of Japanese dive-bombing. One is not likely to be hit, but the difficulty lies in assuring oneself in advance that one is not going to be.

Dark memories are at work there, despite the light, deprecatory tone. And when the author writes of Cormorants that ‘One only has to see them, slowly winging their way home against the red glow of a fading sun, to realize why Milton gave Satan the shape of a cormorant’, it is not difficult to hear further echoes of war: a recollection, perhaps, of other dark, threatening shapes purposefully crossing the sky at dusk.

It is notable, however, that when the war is consciously evoked in British Sea Birds it is to suggest not trauma or fear but resilience. The setting for the book, after all, is the British coast, the natural rampart of land and sea which had kept the invader at bay through the long years of conflict. Any disruption the war had brought to the birds themselves was short-lived and insignificant: a number of Gannet colonies, Gibson-Hill remarks, ‘were used for bombing practice, but the damage does not seem to have been serious’. The message is that whatever turmoil the war may have brought, it was temporary: the patterns of natural life continued regardless.

By the summer of 1947 Gibson-Hill was back in Singapore. For him, as for so many of the expatriate servants of Empire, it was Britain that was a remote and little-known land: his only real home was in a country and among a people not his own. He was a prominent figure in colonial Singapore, becoming Director of the Raffles Museum in 1957; but by the early 1960s independence was approaching, and with it the loss for Gibson-Hill of career, home and social position. In addition, he feared that his already poor eyesight was deteriorating further, and that he, the indefatigable and precise observer and recorder of the world around him, was going blind. The impending loss of everything that mattered to him seems to have been too much to bear, and on 18 August 1963 he killed himself with an overdose of sleeping tablets.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 34 © Ralph Harrington 2012

About the contributor

Ralph Harrington is a historian who has long been interested in birds. His own contribution to British bird-watching took place during a field trip on the Isle of Purbeck in 1977 when, over stimulated by the sight of a Dartford Warbler, he wandered off into the Dorset countryside, became lost, and had to be rescued by the police.