When Richard Hughes looked back at how he wrote his first and most successful novel, he described the process rather beguilingly. In 1926, when he was 26, he retired for the winter ‘to the little Adriatic island town of Capodistria, where the exchange was then so favourable that I could live on next to nothing – which is all I had – and where the only language spoken was Italian, of which (at first at any rate) I knew not a word, so that I could work all day in the Café della Loggia undisturbed by the chatter’. He wrote in this semi-operatic self-exile with such meticulous care that just one chapter was completed before his winter was over. ‘This may seem slow going but I had decided my book was to be a short one and it is always what a writer leaves out of his book, not what he puts in, that takes the time.’

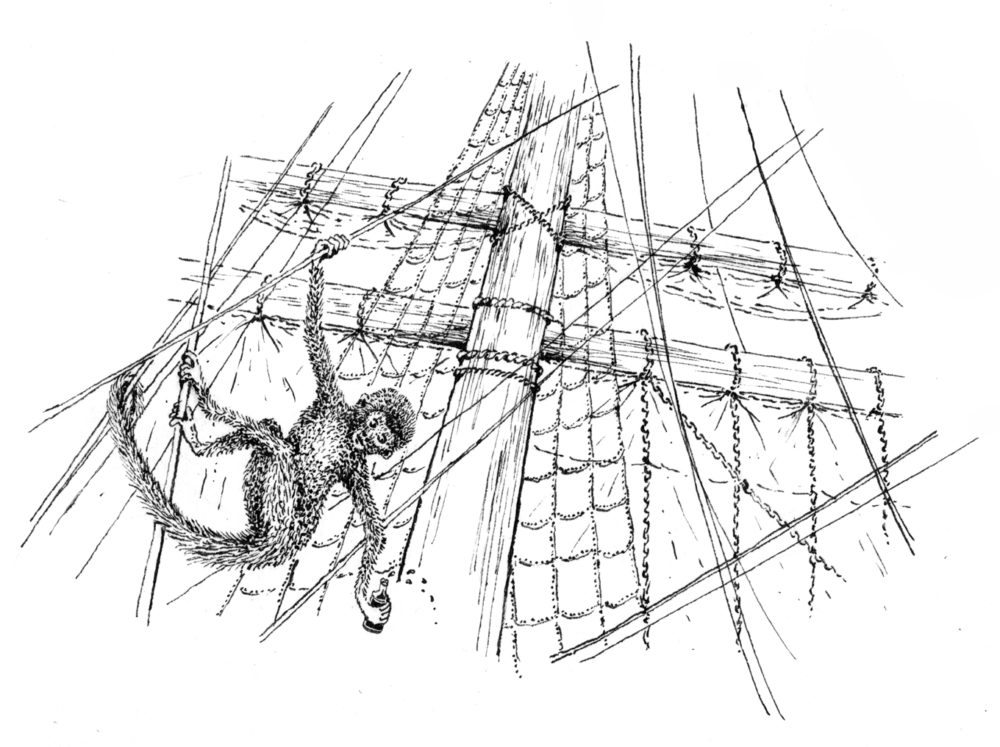

The book was A High Wind in Jamaica (1929) and it is indeed a short book, but one that grips and fizzes with ideas, images and energy. Thirty-five years ago, as an inexperienced schoolteacher, I had the task of interesting a class of 16-year-olds in it, and I thought it would be ideal fare for them. Set around the middle of the nineteenth century, the novel takes the outward form of an adventure story. The ingredients are a group of children and their life on a decayed plantation, then an earthquake, a hurricane, a sailing ship, the high seas, the capture of the children by pirates and a final rescue and return to normality in England. The passing incidents include some farcical goings-on with pirates dressed as women, a ludicrous quayside auction of the pirates’ booty, some uproarious banqueting, a fight between a goat and a pig, another between a tiger and a lion – or an attempt to stage one – and a chase after a drunken monkey in the ship’s rigging. So far, so Pirates of the Caribbean; but there

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhen Richard Hughes looked back at how he wrote his first and most successful novel, he described the process rather beguilingly. In 1926, when he was 26, he retired for the winter ‘to the little Adriatic island town of Capodistria, where the exchange was then so favourable that I could live on next to nothing – which is all I had – and where the only language spoken was Italian, of which (at first at any rate) I knew not a word, so that I could work all day in the Café della Loggia undisturbed by the chatter’. He wrote in this semi-operatic self-exile with such meticulous care that just one chapter was completed before his winter was over. ‘This may seem slow going but I had decided my book was to be a short one and it is always what a writer leaves out of his book, not what he puts in, that takes the time.’

The book was A High Wind in Jamaica (1929) and it is indeed a short book, but one that grips and fizzes with ideas, images and energy. Thirty-five years ago, as an inexperienced schoolteacher, I had the task of interesting a class of 16-year-olds in it, and I thought it would be ideal fare for them. Set around the middle of the nineteenth century, the novel takes the outward form of an adventure story. The ingredients are a group of children and their life on a decayed plantation, then an earthquake, a hurricane, a sailing ship, the high seas, the capture of the children by pirates and a final rescue and return to normality in England. The passing incidents include some farcical goings-on with pirates dressed as women, a ludicrous quayside auction of the pirates’ booty, some uproarious banqueting, a fight between a goat and a pig, another between a tiger and a lion – or an attempt to stage one – and a chase after a drunken monkey in the ship’s rigging. So far, so Pirates of the Caribbean; but there is also a dark side: the shocking accidental death of a child, a murder, a fatal betrayal and a hanging. A High Wind in Jamaica has often been compared to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies in that both stories take as their starting-point popular nineteenth-century children’s tales and give a twist to their basic premises: Golding, writing in the early 1950s, destroyed the noble innocence of R. M. Ballantyne’s young protagonists in Coral Island while, almost thirty years earlier, Hughes’s had taken another famous juvenile adventure, Treasure Island, and daringly reimagined it as a study of the mystery of the child-psyche at the approach of puberty. To my surprise the teenagers in my class were underwhelmed by the book, and many hated it altogether. I puzzled over this. Perhaps it was that most teenagers, having recently left childhood behind, didn’t appreciate having to dwell on it again, whatever the context. Moreover the children in this story appear decidedly odd. Events are largely seen through the haunted eyes of 10-year-old Emily who, by contrast with most children in fiction, is complex, egotistical, hypersensitive and far from innocent. Wary in general of moral ambiguity, my pupils found they didn’t like her, and would have preferred a more sympathetic central character, whom they could root or feel sorry for – Ralph in Lord of the Flies fitted the bill or, in another stalwart of the O-level curriculum, Snowball in Animal Farm. The students’ thumbs-down to the book might have been attributable to my falling short as a teacher, but there is a much more serious problem about A High Wind in Jamaica as a schoolroom text, which has now (as far as I know) resulted in its permanent banishment from the GCSE curriculum. Though there are three boys in A High Wind’s cast, Hughes is hardly interested in them as characters. All his concentration is on young Emily and (to a lesser extent) the other girls, Margaret, Rachel and Laura. For a man to write a story about female children from, as it were, the inside cannot in itself be held against him. But Hughes takes the extraordinary risk of introducing sex into the project. It is not explicit, yet it hovers fitfully, like a spectre, over the future of the young hostages. Margaret is 13 and becoming sexually aware. Soon after being taken aboard the pirate ship she leaves the children’s accommodation to sleep in the cabin and to spend all her time with the pirates. Her absence is not interpreted, but it subtly changes the atmosphere of the story in a way that the reader knows can never be reversed. Then there are the equally touchy questions of slavery and race. When taken hostage by the pirates, the children are passengers to England from Jamaica, where their homes have been flattened by the aforementioned hurricane. Emily and her siblings had lived on an old sugar estate, not worked since the (relatively recent) emancipation of the slaves. That is the background to the thoughts that come to her in the immediate aftermath of the storm:It was not the hurricane she was thinking of, it was the death of Tabby. That, at times, seemed a horror beyond all bearing. It was her first intimate contact with death – and a death of violence, too. The death of Old Sam had no such effect: there is, after all, a vast difference between a negro and a favourite cat.Such words in print must shock to the bone anyone in education today. You could say, as I myself did in the 1970s, no matter: the challenge is an educational one. You have to explore Hughes’s words in context – their dramatic irony, the fact that they are the callous thoughts of a child – and you should also take a historical perspective: just because something is unthinkable now does not mean it was not, once, as thinkable to some people as hopscotch or lemon pie. But what if an anti-racist parent should read this passage? What if it were taken up by racist children in the school playground? Books have been removed from library shelves for containing less incendiary statements. Far better to avoid these confrontations. There is no doubt that the long-term careers of certain books can be blighted if educators take against them. While Animal Farm’s stock has risen ever higher, and Lord of the Flies has never dropped out of print, A High Wind has shifted uneasily (and I suppose unprofitably) around the publishing map as successive publishers have reissued it and then let it fall out of print. Yet the book is a master class in how to tell a story – emotionally oblique and happy to leave its readers to do a good deal of interpretive work for themselves, and at the same time exceptionally alert to imagery, characterization, literary irony and moral subtext. That makes it sound like a dutiful series of Lit. Crit. boxes ticked. But re-reading it after more than three decades I found that A High Wind brings all its ingredients together like a perfectly cooked meal to present a tale full of texture and tastes. It is immensely satisfying. For a starter we have the compelling set-piece description of the hurricane in the section said by the author to have been the sole product of his stay in Capodistria.

The negro huts were clean gone, and the negroes crawling on their stomachs across the compound to gain the shelter of the house. The bouncing rain seemed to cover the ground with a white smoke, a sort of sea in which the blacks wallowed like porpoises. One nigger-boy began to roll away: his mother, forgetting caution, rose to her feet: and immediately the fat old beldam was blown clean away, bowling along across the fields and hedgerows like someone in a funny fairy story, till she fetched up against a wall and was pinned there, unable to move.The rest of Hughes’s meal is served up with equal panache and conviction. A great part of his attraction as a narrator is that he knows things. He can describe what it is like to encounter an octopus when diving, or to stand above a beach and witness the proximate effects of a deep-sea earthquake. He understands the nature of a sea-going schooner to be ‘one of the most mechanically satisfactory, austere, unornamented engines ever invented by Man’. He knows the effect of seasickness on a lion, the capabilities of a monkey under the influence of rum, how to make ‘that potion known in alcoholic circles as Hangman’s Blood’. There are times, after the tumultuous opening, when the narrative slows down, and nothing much appears to be happening. In fact things are happening but the adults are out of sight, or on the periphery, while the children are left to discover the pleasures of life on a sailing vessel.

The most lasting joy undoubtedly lay in that network of footropes and chains and stays that spreads out under and on each side of the bowsprit. Here familiarity only bred content. Here, in fine weather, one could climb or be still: stand, sit, hang, swing or lie: now this end up, now that: and all with the cream of the blue sea being whipt up for one’s own special pleasure, almost within touching distance.This is prose under perfect cadenced control. It sometimes rises very near poetry:

The schooner moved just enough for the sea to divide with a slight rustle on her stem, breaking out into a shower of sparks, which lit up also wherever the water rubbed the ship’s side, as if the ocean were a tissue of sensitive nerves; and still twinkled behind in the paleness of the wake.The narrative never stands still for long, however, and when the end approaches it comes quickly, and with brutal finality for the pirates. As they stand trial at the Old Bailey – not merely for piracy but for a murder they did not commit – Hughes nicely conveys the curious atmosphere of a criminal courtroom, and just how a judge might seem to an imaginative child witness (Emily, in fact): ‘dressed in his strange disguise, toying with a pretty nosegay, he looked like some benign old wizard who spent his magic in doing good’. When the trial is over Emily still doesn’t acknowledge what she has been involved in, and asks her father, ‘What was it all about? Why did I have to learn all those questions?’ But it is those questions, or rather the answers that Emily has been coached to learn by heart, that write the death warrant for the pirate captain Olson, Otto his mate, and the rest. Emily is far from stupid and by no means incapable of understanding the fatal role she has played in the trial. She simply suppresses the knowledge. Much earlier on, while still aboard Jonsen’s schooner, a wave of self-consciousness suddenly breaks over her and she cries out to herself (in an echo of another child involved with pirates), ‘Oh, why must she grow up?’ Many novelists would wrap up such a story with the conclusion that Emily, after all her extraordinary experiences, has grown up. But this is not Richard Hughes’s conception of Emily. She may know she will, she must, become an adult – but slyly, and protected by a cloak of false innocence, she will put off reaching that crux of responsibility, and will do so for as long as she possibly can. The account by Hughes of his visit to Capodistria in 1926 omits at least one significant fact: he had gone abroad in full flight from a callow and disastrous sexual affair. Perhaps that is the hidden key to this great book’s bittersweet and, I think, tragic view of the life of a child – a life inescapably innocent and guilty, outgoing and self-absorbed, clung-to and betrayed.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 42 © Robin Blake 2014

About the contributor

Robin Blake’s third novel about the Georgian coroner of Preston, Titus Cragg, will be published in the New Year. He lives partly in London and partly in the eighteenth century.