I like to think we run an open-door policy in our library at home in Norfolk. That is to say, on warm days in summer the door to the garden is actually open. Anyone’s welcome to come in for a browse. Last summer a stoat wandered in, peered dismissively at the modest shelf of my own titles, sniffed about under my desk and then ambled out. Most Julys the house ants – here long before us and so given due respect – pour out from alarming new holes in the floor, march along the tops of my editions of Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne, and shuffle in a lost and desultory way about the carpet, seeming uninterested in getting outdoors for their nuptial flights. But while I fret about the continuance of their ancient lineage, the culling is already under way. Next through the door come the bolder blackbirds and robins, hoovering the insects up in front of the shelves.

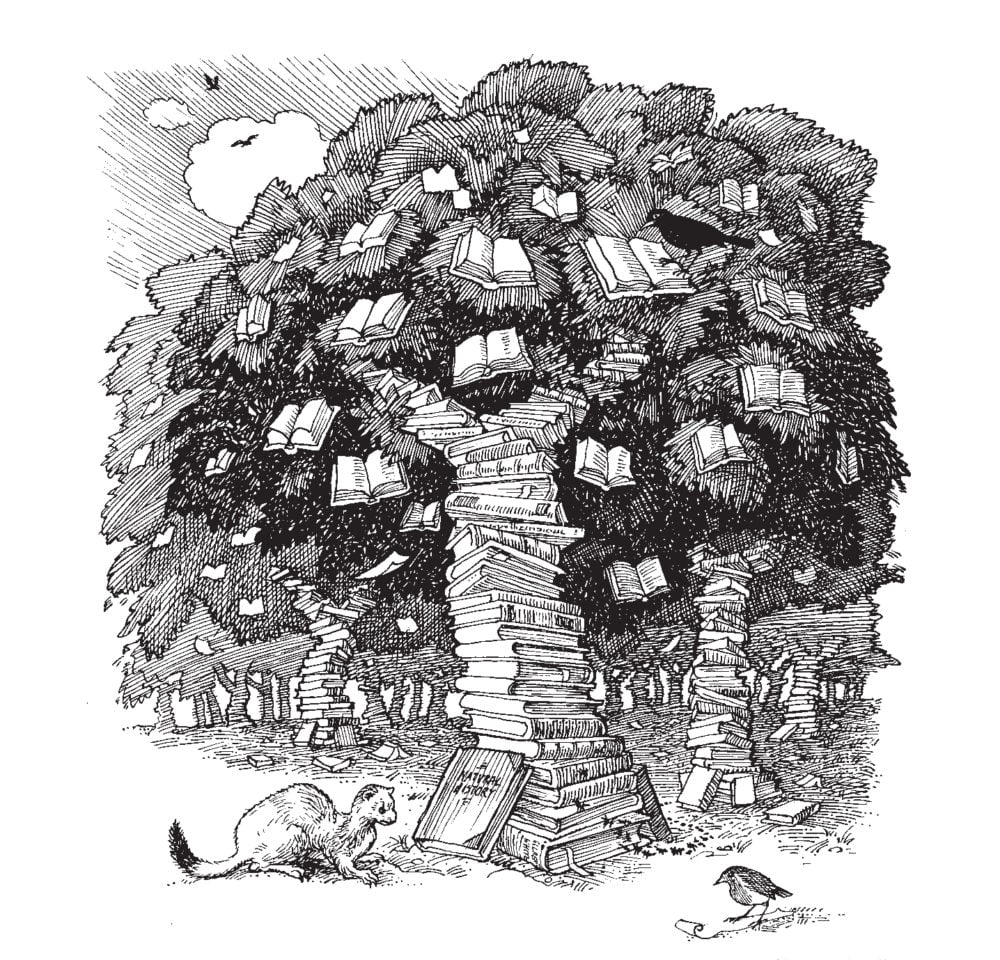

I think it’s entirely proper that the place is a working natural habitat, the word library emerging from the Latin liber, which described a bit of bark inscribed with letters, and having secondary meanings to do with the liberties of the marketplace. A collection of books begins, I guess, as a kind of landscape. You plan its geological layers, cliffs, niches, ante-chambers. Hillocks and book-quakes erupt where the mass gets critical. And your Organizing System is probably more Capability Brown than Dewey Decimal. Inside this, as I’m sure is true with all booklovers, the whole house becomes ‘landskipp’d’.

In our sixteenth-century farmhouse fiction and poetry reside chiefly in the living-room, some in a disused open hearth. Children’s books are halfway up the stairs. An entirely irrational combination of dictionaries and field guides and American non-fiction swarm in a room in the one-time outhouse that I use as an office. Almost everything else lives in what I have rather grandly called ‘the library’. In here I try to keep a semblance of order by arranging technical and academic books under subjects, and others alphabetically under author, on the dubious assumption that this ordering will mesh better with my memory. One writer I know arranges her travel books in order of the mean temperature of the region they’re set in.

And this is the point, needless to say, where the library ceases to have the immemorial structure of a landscape and edges towards the rampant wildness of an ecosystem, with an agenda of its own. An old bibliophile’s saw is that if you gaze at the spines of your books for long enough, you absorb the contents by a kind of chiromancy. I’m increasingly finding I have to gaze at the spines just to locate them. Pattern recognition, an entomologist would call it. I can never remember either the title or the authors of The Garden, the Ark, the Tower and the Temple: Biblical Metaphors of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe, but I can always find it because it is edged with a distinctive pale-blue mottle of Edenic animals and plants, and lives high in the canopy (how apt that ‘leaves’ are common to both books and boskiness). And for all one’s high intentions, orderliness seems to be wilfully disrupted by unintended and provocative conjunctions. It needed no intervention to make the philosopher and foxhunter Roger Scruton’s unimpeachably conservative memoir News from Somewhere (in which he marries a girl ‘whom I had seen poised aloft in Beaufort colours – like a painted angel in a frame’) stand in mischievous dialectic next to Alfred Schmidt’s severe The Concept of Nature in Marx. But I have no recollection of slightly tweaking the authorial alphabet so that David Hendy’s Noise: A Human History of Sound and Listening sits serendipitously adjacent to Adam Gopnik’s lyrical essays on Winter, with their description of the hiss and spark of Wordsworth’s Lake District skating. The library is having ideas here before I do.

But it’s the seasons of migration that really throw the wild card into the packed shelves. When I’m on a big project, I usually ferry a week’s worth of likely reference sources from their various winter quarters over to where I do the actual writing. So armfuls of paper, from thin downloaded journal articles to eighteenth-century folios, cross parts of the garden like herds of wildebeest, and are set down in the library. There’s no room for them of course, so they go on the floor in strange rows and clusters that I have never glimpsed just so before. Just at the moment I am, for a book on plants and the imagination, trying to make sense of the relation between biological mimicry and literary metaphor (both cases of ‘this stands for that’). The line of immediately pertinent texts is bookended by a heavy-framed Richard Cartwright painting of a white whale swimming in a black sea under a white cloud. The title at one end is Colonel Godfrey’s classic 1933 monograph, Native British Orchidaceae – the only book I have seen where the dedication page is dominated by a photograph of the dedicatee, Godfrey’s beloved late wife Hilda, posed amid the foliage in her garden. At the other is William Anderson’s The Green Man (rather archly sub-titled ‘An Archetype of our Oneness with the Earth’) and I ponder, prompted by their proximity, whether Hilda was a kind of Green Woman, and the degree to which foliated hybrids permeate our imaginations.

This row, in ecological jargon, would be called a ‘guild’, a set of organisms that all fill similar roles or do analogous jobs. Trees that grow in swamps form a guild. So do insects with a taste for carrion. My current books are a guild in that they are all loyally devoted to a single purpose – helping me get this chapter sorted. But they are also, ecologically speaking, an ‘association’, a community of species which live together in one place, usually in some kind of mutually beneficial relationship. The insects, plants, fungi and bacteria that make up a termite mound comprise an association. Groups of books, often for entirely sentimental reasons, have been taken out of the library’s chaotic but well-meant order and encouraged to associate. I have one small bookcase – more ant-hill than termite condominium – entirely devoted to the works of John Clare and Ronald Blythe. I thought they would be happy together not only because Ronnie has been such a champion of and prolific writer about Clare, but because they both grant huge significance to the places where things dwell – and what principle is more important in a library? One of the choicer items in the Blythe section is an inscribed edition of the lecture he delivered at the Royal Society of Arts’ Nobel Symposium in 1980, entitled ‘An Inherited Perspective’. In it he describes his shock at glimpsing John Clare’s village of Helpston from an express train, ‘first the platform name, and then the niggard features of one of the most essential native landscapes in English literature’. He had not even realized it was on a railway line.

Margaret Grainger’s collection of The Natural History Prose Writing of John Clare (1983) quotes his graphic and curmudgeonly account of the sixteen species of wild orchid that grew round Helpston. Denouncing botanical science as the ‘Dark System’, swatting aside even the Bard himself, he proclaims the natural rightness of vernacular names: ‘let the commentators of Shakspear say what they will nay shakspear himself has no authority for me in this particular the vulgar were ever I have been know them by [these names] only & the vulgar are always the best glossary to such things’. What emerges is not just a lexicon of popular names but a vivid list of the orchid’s addresses. The early marsh-orchid, one of Clare’s ‘cuckoo buds’, was ‘very plentiful before the Enclosure on a Spot called Parker’s Moor near Peasfield-hedge & on Deadmoor near Sneef green & Rotten moor by Moorclose but these places are now all under the plow’.

Clare is by no means the only writer to have ‘named’ and ascribed the identity of a plant by its dwelling-place. When Wordsworth’s famous ‘Primrose of the Rock’, once an anchor in his Lakeland life, had degenerated into a banal religious symbol, his sister Dorothy nailed it firmly back to earth in her subtitle for William’s final verses on the flower: ‘Written in March 1829 on seeing a Primrose-tuft of flowers flourishing in the chink of a rock in which that Primrose tuft had been seen by us to flourish for twenty nine seasons’. The great Romantic scholar Professor Lucy Newlyn thinks that ‘such elaborate specificity suggests she saw the poem as belonging to the “Inscription” genre, normally used to commemorate connections between people and places’. I first had contact with Lucy when she sent me a copy of her delightful paper on literary glowworms, which should by rights be living close to the book from which I have just quoted, William and Dorothy Wordsworth: All in Each Other (2013), but which for reasons of its own, has migrated to the outhouse, and a sub-sub-section of ‘special gifts’ . . .

You may begin to see where I am going in this round-the-bushes digression. Inscriptions, connections, authors, places – all prime librarious issues. Back in the book room the real problem comes when those briefly privileged titles have to go back ‘where they belong’. Some hope. They’ve acquired new acquaintances, new guild partners, so their belonging has become a serious existential problem. Frankly, I’m often tempted to give up any pretence of order, and arrange the whole lot by free association, so that the library would become a leaf-space as vivaciously mobile as a rainforest. I’d never find anything I wanted, but just imagine the new symbioses and connectivities I’d discover, by – to only marginally misuse the term for what drives evolution – natural selection.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 47 © Richard Mabey 2015

About the contributor

Richard Mabey is currently finishing Efflorescence: The Cabaret of Plants on a Visiting Fellowship at Cambridge, and is rationing himself to six titles in his room at a time ‘so that I get thirsty for oases’.