A life is made up of a great number of small incidents and a small number of great ones: an autobiography must therefore, unless it is to become tedious, be extremely selective, discarding all the inconsequential incidents in one’s life and concentrating upon those that have remained vivid in the memory.

The first part of this book takes up my own personal story precisely where my earlier autobiography, which was called Boy, left off. I am away to East Africa on my first job, but because any job, even if it is in Africa, is not continuously enthralling, I have tried to be as selective as possible and have written only about those moments that I consider memorable.

In the second part of the book, which deals with the time I went flying with the RAF in the Second World War, there was no need to select or discard because every moment was, to me at any rate, totally enthralling.

RD

The Battle of Athens – the Twentieth of April

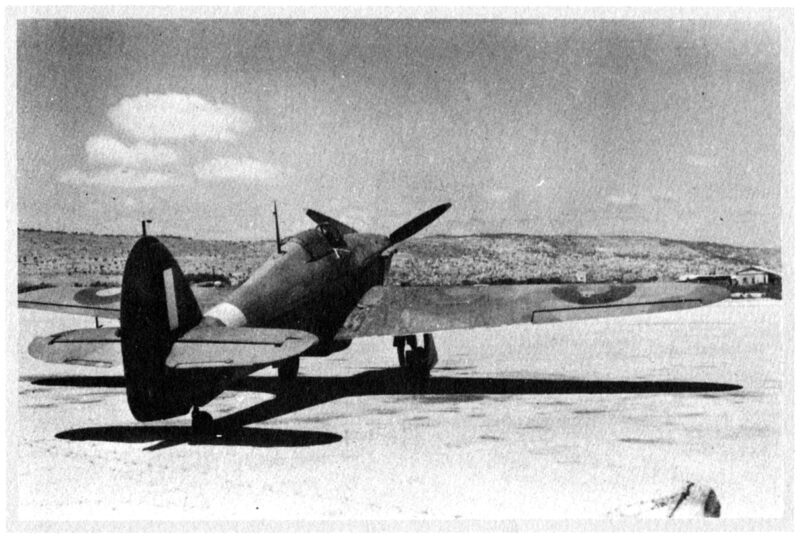

The next three days, 17, 18 and 19 April 1941, are a little blurred in my memory. The fourth day, 20 April, is not blurred at all. My Log Book records that from Eleusis aerodrome

on 17 April I went up three times

on 18 April I went up twice

on 19 April I went up three times

on 20 April I went up four times.

Each one of those sorties meant running across the airfield to wherever the Hurricane was parked (often 200 yards away), strapping in, starting up, taking off, flying to a particular area, engaging the enemy, getting home again, landing, reporting to the Ops Room and then making sure the aircraft was refuelled and rearmed immediately so as to be ready for another take-off.

Twelve separate sorties against the enemy in four days is a fairly hectic pace by any standards, and each one of us knew that every time a sortie was made, somebody was probably going to get killed, either the Hun or the man in the Hurricane. I used to figure that the betting on every flight was about even money against my coming back, but in reality it wasn’t even money at all. When you are outnumbered by at least ten to one on nearly every occasion, then a bookmaker, had there been one on the aerodrome, would probably have been willing to lay something like five to one against your return on each trip.

Like all the others, I was always sent up alone. I wished I could sometimes have had a friendly wing-tip alongside me, and more importantly, a second pair of eyes to help me watch the sky behind and above. But we didn’t have enough aircraft for luxuries of that sort.

Sometimes I was over Piraeus harbour, chasing the Ju 88s that were bombing the shipping there. Sometimes I was around the Lamia area, trying to deter the Luftwaffe from blasting away at our retreating army, although how anyone could think that a single Hurricane was going to make any difference out there was beyond me. Once or twice, I met the bombers over Athens itself, where they usually came along in groups of twelve at a time. On three occasions my Hurricane was badly shot up, but the riggers in 80 Squadron were magicians at patching up holes in the fuselage or mending a broken spar. We were so frantically busy during these four days that individual victories were hardly noticed or counted. And unlike the fighter aircraft back in Britain, we had no camera-guns to tell us whether we had hit anything or not. We seemed to spend our entire time running out to the aircraft, scrambling, dashing off to some place or other, chasing the Hun, pressing the firing-button, landing back at Eleusis and going up again.

My Log Book records that on 17 April we lost Flight-Sergeant Cottingham and Flight-Sergeant Rivelon and both their aircraft.

On 18 April Pilot Officer Oofy Still went out and did not return. I remember Oofy Still as a smiling young man with freckles and red hair.

That left us with twelve Hurricanes and twelve pilots with which to cover the whole of Greece from 19 April onwards.

As I have said, 17, 18 and 19 April seem to be all jumbled up together in my memory, and no single incident has remained vividly with me. But 20 April was quite different. I went up four separate times on 20 April, but it was the first of these sorties that I will never forget. It stands out like a sheet of flame in my memory.

On that day, somebody behind a desk in Athens or Cairo had decided that for once our entire force of Hurricanes, all twelve of us, should go up together. The inhabitants of Athens, so it seemed, were getting jumpy and it was assumed that the sight of us all flying overhead would boost their morale. Had I been an inhabitant of Athens at that time, with a German army of over 100,000 advancing swiftly on the city, not to mention a Luftwaffe of about 1,000 planes all within bombing distance, I would have been pretty jumpy myself, and the sight of twelve lonely Hurricanes flying overhead would have done little to boost my morale.

However, on 20 April, on a golden springtime morning at ten o’clock, all twelve of us took off one after the other and got into a tight formation over Eleusis airfield. Then we headed for Athens, which was no more than four minutes’ flying time away.

I had never flown a Hurricane in formation before. Even in training I had only done formation flying once in a little Tiger Moth. It is not a particularly tricky business if you have had plenty of practice, but if you are new to the game and if you are required to fly within a few feet of your neighbour’s wing-tip, it is a dicey experience. You keep your position by jiggling the throttle back and forth the whole time and by being extremely delicate on the rudder-bar and the stick. It is not so bad when everyone is flying straight and level, but when the entire formation is doing steep turns all the time, it becomes very difficult for a fellow as inexperienced as I was.

Round and round Athens we went, and I was so busy trying to prevent my starboard wing-tip from scraping against the plane next to me that this time I was in no mood to admire the grand view of the Parthenon or any of the other famous relics below me. Our formation was being led by Flight-Lieutenant Pat Pattle. Now Pat Pattle was a legend in the RAF. At least he was a legend around Egypt and the Western Desert and in the mountains of Greece. He was far and away the greatest fighter ace the Middle East was ever to see, with an astronomical number of victories to his credit. It was even said that he had shot down more planes than any of the famous and glamorized Battle of Britain aces, and this was probably true. I myself had never spoken to him and I am sure he hadn’t the faintest idea who I was. I wasn’t anybody. I was just a new face in a squadron whose pilots took very little notice of each other anyway. But I had observed the famous Flight-Lieutenant Pattle in the mess tent several times. He was a very small man and very soft-spoken, and he possessed the deeply wrinkled doleful face of a cat who knew that all nine of its lives had already been used up.

On that morning of 20 April, Flight-Lieutenant Pattle, the ace of aces, who was leading our formation of twelve Hurricanes over Athens, was evidently assuming that we could all fly as brilliantly as he could, and he led us one hell of a dance around the skies above the city. We were flying at about 9,000 feet and we were doing our very best to show the people of Athens how powerful and noisy and brave we were, when suddenly the whole sky around us seemed to explode with German fighters. They came down on us from high above, not only 109s but also the twin-engined 110s. Watchers on the ground say that there cannot have been fewer than 200 of them around us that morning. We broke formation and now it was every man for himself. What has become known as the Battle of Athens began.

I find it almost impossible to describe vividly what happened during the next half-hour. I don’t think any fighter pilot has ever managed to convey what it is like to be up there in a long-lasting dog fight. You are in a small metal cockpit where just about everything is made of riveted aluminium. There is a plexiglass hood over your head and a sloping bullet-proof windscreen in front of you. Your right hand is on the stick and your right thumb is on the brass firing-button on the top loop of the stick. Your left hand is on the throttle and your two feet are on the rudder-bar. Your body is attached by shoulder-straps and belt to the parachute you are sitting on, and a second pair of shoulder-straps and a belt are holding you rigidly in the cockpit. You can turn your head and you can move your arms and legs, but the rest of your body is strapped so tightly into the tiny cockpit that you cannot move. Between your face and the windscreen, the round orange-red circle of the reflector-sight glows brightly.

Some people do not realize that although a Hurricane had eight guns in its wings, those guns were all immobile. You did not aim the guns, you aimed the plane. The guns themselves were carefully sighted and tested beforehand on the ground so that the bullets from each gun would converge at a point about 150 yards ahead. Thus, using your reflector-sight, you aimed the plane at the target and pressed the button. To aim accurately in this way requires skilful flying, especially as you are usually in a steep turn and going very fast when the moment comes.

Over Athens on that morning, I can remember seeing our tight little formation of Hurricanes all peeling away and disappearing among the swarms of enemy aircraft, and from then on, wherever I looked I saw an endless blur of enemy fighters whizzing towards me from every side. They came from above and they came from behind and they made frontal attacks from dead ahead, and I threw my Hurricane around as best I could and whenever a Hun came into my sights, I pressed the button. It was truly the most breathless and in a way the most exhilarating time I have ever had in my life. I caught glimpses of planes with black smoke pouring from their engines. I saw planes with pieces of metal flying off their fuselages. I saw the bright-red flashes coming from the wings of the Messerschmitts as they fired their guns, and once I saw a man whose Hurricane was in flames climb calmly out on to a wing and jump off. I stayed with them until I had no ammunition left in my guns. I had done a lot of shooting, but whether I had shot anyone down or had even hit any of them I could not say. I did not dare to pause for even a fraction of a second to observe results. The sky was so full of aircraft that half my time was spent in actually avoiding collisions. I am quite sure that the German planes must have often got in each other’s way because there were so many of them, and that, together with the fact that there were so few of us, probably saved quite a number of our skins.

When I finally had to break away and dive for home, I knew my Hurricane had been hit. The controls were very soggy and there was no response at all to the rudder. But you can turn a plane after a fashion with the ailerons alone, and that is how I managed to steer the plane back. Thank heavens the undercarriage came down when I engaged the lever, and I landed more or less safely at Eleusis. I taxied to a parking place, switched off the engine and slid back the hood. I sat there for at least one minute, taking deep gasping breaths. I was quite literally overwhelmed by the feeling that I had been into the very bowels of the fiery furnace and had managed to claw my way out. All around me now the sun was shining and wild flowers were blossoming in the grass of the airfield, and I thought how fortunate I was to be seeing the good earth again. Two airmen, a fitter and a rigger, came trotting up to my machine. I watched them as they walked slowly all the way round it. Then the rigger, a balding middle-aged man, looked up at me and said, ‘Blimey mate, this kite’s got so many ’oles in it, it looks like it’s made out of chicken-wire!’

I undid my straps and eased myself upright in the cockpit. ‘Do your best with it,’ I said. ‘I’ll be needing it again very soon.’

I remember walking over to the little wooden Operations Room to report my return and as I made my way slowly across the grass of the landing field I suddenly realized that the whole of my body and all my clothes were dripping with sweat. The weather was warm in Greece at that time of year and we wore only khaki shorts and khaki shirt and stockings even when we flew, but now those shorts and shirt and stockings had all changed colour and were quite black with wetness. So was my hair when I removed my helmet. I had never sweated like that before in my life, even after a game of squash or rugger. The water was pouring off me and dripping to the ground. At the door of the Ops Room three or four other pilots were standing around and I noticed that each one of them was as wet as I was. I put a cigarette between my lips and struck a match. Then I found that my hand was shaking so much I couldn’t put the flame to the end of the cigarette. The doctor, who was standing nearby, came up and lit it for me. I looked at my hands again. It was ridiculous the way they were shaking. It was embarrassing. I looked at the other pilots. They were all holding cigarettes and their hands were all shaking as much as mine were. But I was feeling pretty good. I had stayed up there for thirty minutes and they hadn’t got me.

They got five of our twelve Hurricanes in that battle. One of our pilots baled out and was saved. Four were killed. Among the dead was the great Pat Pattle, all his lucky lives used up at last. And Flight-Lieutenant Timber Woods, the second most experienced pilot in the squadron, was also among those killed. Greek observers on the ground as well as our own people on the airstrip saw the five Hurricanes going down in smoke, but they also saw something else. They saw twenty-two Messerschmitts shot down during that battle, although none of us ever knew who got what.

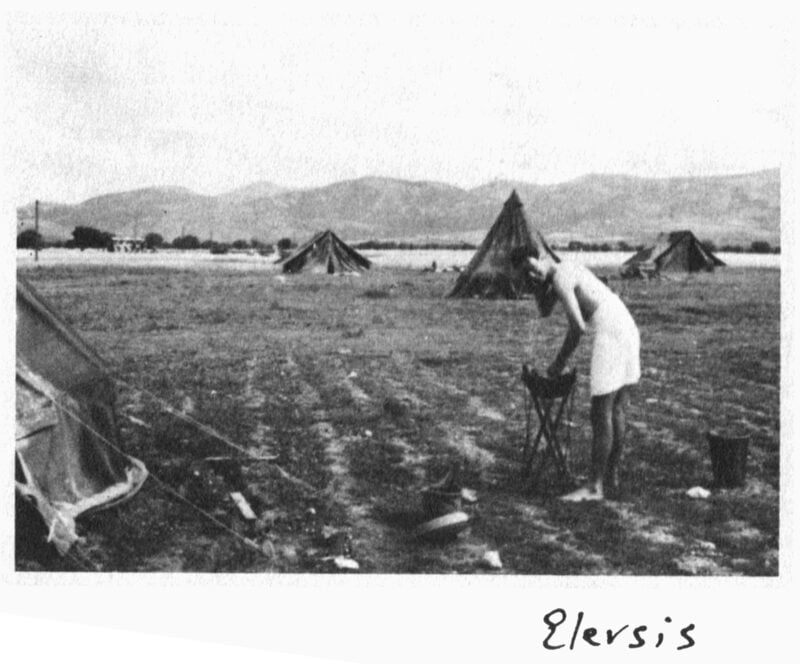

So we now had seven half-serviceable Hurricanes left in Greece, and with these we were expected to give air cover to the entire British Expeditionary Force which was about to be evacuated along the coast. The whole thing was a ridiculous farce. I wandered over to my tent. There was a canvas washbasin outside the tent, one of those folding things that stand on three wooden legs, and David Coke was bending over it, sloshing water on his face. He was naked except for a small towel round his waist and his skin was very white. ‘So you made it,’ he said, not looking up.

‘So did you,’ I said.

‘So did you,’ I said.

‘It was a bloody miracle,’ he said. ‘I’m shaking all over.

What happens next?’

‘I think we’re going to get killed,’ I said.

‘So do I,’ he said. ‘You can have the basin in a moment. I left a bit of water in the jug just in case you happened to come back.’

Extract from Going Solo © Roald Dahl 1986

Another very graphic account – in rather more detail, disarmingly frank and immediate – can be found in The Big Show by Pierre Closterman DFC. In his description of abject terror, attacking ‘No Balls’ – V1 launch sites, below treetop height, in a Spitfire – he describes his toes being curled up in his boots – the air filled with tracer from the emplacements they were attacking, ducking behind trees . . . A very compelling read – everytime! R.