We had walked the white sands of Luskentyre in a wild wind that left grains in our hair and salt on our lips. The shadows of clouds skimmed across the face of Taransay, indigo over the water. Somebody had scuffed the word ‘Scotland’ with their shoe on the shore. We added ‘Atlantis’, with an arrow pointing west.

It was time to find some warmth again so we wound our way slowly along the single-track road, steering around the sleeping, scratching or munching sheep, until we came to the little bay. We soon had a fire going in the hollow grate of the cottage, and sighed as the rain rattled on the panes. There was one dark bookcase in the corner. The shelves held worn volumes about the sea, birds, fish, islands and weaving. Here on the Isle of Harris in the Outer Hebrides they were the things that mattered, along with the peat stacked like black playing-cards out on the machair, and the stones, grey and gnarled as old bones.

Some of the books I already knew: Night Falls on Ardnamurchan by Alasdair Maclean, a poet’s journal of his father’s hard crofting life on a remote peninsula, almost an island itself; Off in a Boat, the book Neil Gunn wrote when he gave up his job as a distillery excise-man and set off to sail and to write full-time. And Sea Room, Adam Nicolson’s account of the Shiant Isles, those jagged citadels out to the east of Harris, which he had been given as a twenty-first birthday present.

But now, what was this? Island Going by Robert Atkinson – a paperback reprint of a book published in 1949. Neither author nor title were known to me. I liked the precise but somehow breezy sub-title: ‘To the Remoter Isles, Chiefly Uninhabited, off the North-West Corner of Scotland’. I took a look at the first few pages. Aha! The book barely started and here was a sentence so good I had to read it out loud:

It was a fine morning with heat to come, and when that was over, and the day nearly gone, the hills of Lanark gave back the afterglow of sunset, the whitewashed walls of cottages were pink and old dead grass was the colour of flowering heather.

Just look at the placing of those commas, and listen to the lilt of the words as the sentence nears its end. Here, I knew at once, was a skilful writer who took joy in what he made.

The book proved to be about two students barely out of their teens who go off to look for a bird: to be e

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWe had walked the white sands of Luskentyre in a wild wind that left grains in our hair and salt on our lips. The shadows of clouds skimmed across the face of Taransay, indigo over the water. Somebody had scuffed the word ‘Scotland’ with their shoe on the shore. We added ‘Atlantis’, with an arrow pointing west.

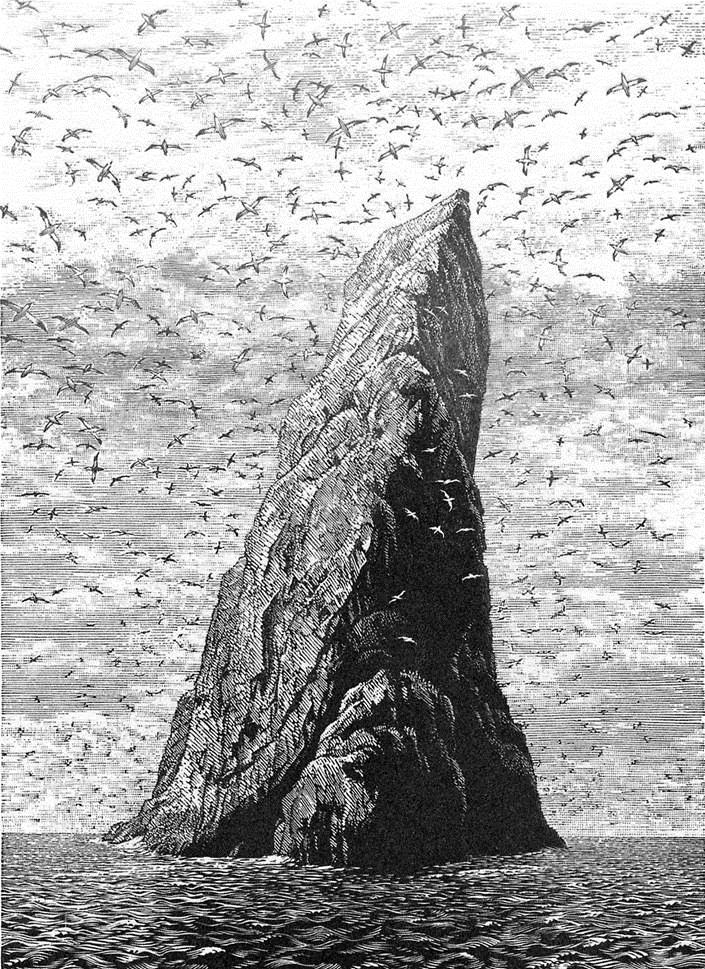

It was time to find some warmth again so we wound our way slowly along the single-track road, steering around the sleeping, scratching or munching sheep, until we came to the little bay. We soon had a fire going in the hollow grate of the cottage, and sighed as the rain rattled on the panes. There was one dark bookcase in the corner. The shelves held worn volumes about the sea, birds, fish, islands and weaving. Here on the Isle of Harris in the Outer Hebrides they were the things that mattered, along with the peat stacked like black playing-cards out on the machair, and the stones, grey and gnarled as old bones. Some of the books I already knew: Night Falls on Ardnamurchan by Alasdair Maclean, a poet’s journal of his father’s hard crofting life on a remote peninsula, almost an island itself; Off in a Boat, the book Neil Gunn wrote when he gave up his job as a distillery excise-man and set off to sail and to write full-time. And Sea Room, Adam Nicolson’s account of the Shiant Isles, those jagged citadels out to the east of Harris, which he had been given as a twenty-first birthday present. But now, what was this? Island Going by Robert Atkinson – a paperback reprint of a book published in 1949. Neither author nor title were known to me. I liked the precise but somehow breezy sub-title: ‘To the Remoter Isles, Chiefly Uninhabited, off the North-West Corner of Scotland’. I took a look at the first few pages. Aha! The book barely started and here was a sentence so good I had to read it out loud:Just look at the placing of those commas, and listen to the lilt of the words as the sentence nears its end. Here, I knew at once, was a skilful writer who took joy in what he made. The book proved to be about two students barely out of their teens who go off to look for a bird: to be exact, Leach’s Fork-tailed Petrel, which the author describes jauntily as ‘like a true ornithologist’s child, cumbrously museum-named and not far removed from the class of lesser yellow-bellied fire-eater’. It is known in Europe only on the remotest, rockiest outcrops of the British Isles. We start ‘in January or February 1935’ with their first expedition to Handa, not far from Cape Wrath. Twelve years later, lots of other islands and a war intervening, we are offered an aerial epilogue as the author takes a flight across the seas even as far as Rockall. But it isn’t just the admirable prose style and the adventurous expeditions that make Island Going so attractive. We come to enjoy the company of the narrator and his pipe-smoking floppy fringed friend John Ainsley, to share with them the many ups and downs of their journeys, the uncertainty about whether they will get a boat to take them out to the furthest isles, the rough weather and bare shelter they find there. There had been a revolution in travel writing at around the time Robert Atkinson and his companion went in search of their fork-tailed treasure. In 1937 Robert Byron’s The Road to Oxiana was published. It was irreverent, sardonic, full of sly humour, self-aware. It was no solemn guidebook, no textbook of dry facts. It shared with the reader the setbacks, the frustrations, the ennui that inevitably accompanies all travel. But it also discussed knowledgeably the things seen on the way: its readers knew they were in the presence of a confident, acute intelligence. Byron’s book of travels in Persia and Afghanistan was not just a discerning and pioneering study of certain Islamic architecture, but a radical new form of travel literature, seen by some as its Ulysses. Robert Atkinson’s book was somewhat in this new style, but without the rather lofty snobbishness sometimes found in Byron. Yes, in essence it was about bird-watching on remote Scottish islands. But it was also about so much more than that: the madcap way that he and his friend drove hundreds of miles in barely roadworthy old crocks; the gentle persistence with which they charmed bemused boat-owners into taking them through storm-tossed seas to rocks rising sheer from the waves; the makeshift shelters they put up on these uninhabited islands; the poignant remains of former human occupation that they recorded; and most of all their genuine and humane curiosity about the puffins, gulls, petrels, seals, sheep and even mice that they encountered. The reader is filled with wonder at their determination, their zest, their knack for improvisation. We are also introduced to the friends they made in the Far North, memorable characters, lightly drawn. There is the retired schoolmistress who writes a weekly column of news from Ness, the headland community at the tip of Lewis, for the local paper the Stornoway Gazette, and who can be relied upon to know what boats are going where. There is the fisheries manager who fixes them up with ships heading their way, looks after their expiring cars, and remains calm and kindly no matter how impractical their ideas. We meet the postmaster of St Kilda (population: three or four) who sells postcards to visiting boats but also sends out messages in bottles to take their chances on the waves. We go with them to North Rona, in the far seas beyond Caithness, to the lighthouse on the Flannan Isles with its miniature railway for hauling stores from the jetty; to the Shiants and, triumphantly, to Sula Sgeir, further out even than North Rona, an outcrop of dark rock sheltering a gannetry, and with the barest clinging of a few hardy weeds. And also what they had come so far to see: a colony of Leach’s Fork-Tailed Petrels. Robert Atkinson served in the navy during the war, unsurprisingly given his seafaring exploits. So did some of his friends: not all returned. A few later chapters in the book, after the war, take us back to some of the places he had visited before, tell us about the fates of the Hebridean friends they had made, note the changes that have come, and also the things that stay perennially the same. I closed the book with that mixture of quiet satisfaction and wistfulness that always remains with the reader who has found an unexpected delight. I was now seized with the need to find out what else the author had written. Surely someone so naturally gifted could not have remained content with just one book, I thought. And I was also so taken by his character that I wanted to find out what happened to him next. At first it seemed that very little was known of him. I’d gathered that he had published one much later book, Shillay and the Seals (1980), about seal-watching on a little-known island off Harris. This at any rate showed that he had not lost his old interests in later life. Here, however, was a more reflective, less tumultuous author, now in his sixties, content to stay for days observing and recording the slow lumbering of the seals on the their rocky roosts, or their slitherings into the sea. But was that all? What had happened in between? Robert Atkinson was a not uncommon name, and the British Library catalogue offered me a bewildering choice of possibilities. Further burrowing revealed that the Robert Atkinson of Island Going was known to the British Library as Robert Atkinson 1915—, that dash still left uncompleted today. And it turned out he had written four books: less than I might have hoped, but still at least there was something more. In fact, there had been a book before the one I had found. It was about a trip to Southern Spain by three Cambridge undergraduates ‘to get the first close-up photograph of the Griffon Vulture at nest’. The expedition described in Quest for the Griffon (1938) had been made just over a year before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and the book’s reception had perhaps been overshadowed by the subsequent glut of volumes telling of a darker Spain, completely changed from the one the trio had traversed. It was easy to see, too, that this first book had not quite the same ease and brio as Island Going. But for all that it was still engaging and great fun to read, with some of the same insouciance, youthful high spirits and quiet determination. The foreword gave a snippet of information about the author, for it was written from ‘Rocky Lane, Henley-on-Thames’. He told us, too, that he had wanted to go in quest of the Griffon ever since, as a prep-school boy, he had seen a picture of it. Robert Atkinson’s third book was altogether different. In 1955 he had contributed to The Countryman Library series, published by Rupert Hart-Davis. Other titles included Keeping Pigs, Eggs for Money and two optimistic-sounding guides, on Wine Growing in England and Figs out of Doors. His own subject was less exotic: Growing Apples. The dustjacket offered another small piece of biographical information: ‘Mr Atkinson, a successful grower himself, who is continuing to plant apples . . .’ it began. Readers as obsessive as I am in pursuit of the work of an author they admire will understand that I had to get this title too. There was a dedication, ‘To Patsy, for much help and encouragement’, and a few black-and-white photographs of what might indeed be Patsy on a tractor. But none of himself. And that was the end of the quest so far: a few more books, a few more facts, but the author himself still remaining strangely elusive. Thinking back to the day I discovered his writing, reading by the fire in a rainwashed Hebridean cottage, I can’t help wondering where Robert Atkinson, always setting out for another, further isle, went next. If anyone could make it to Atlantis, he could.It was a fine morning with heat to come, and when that was over, and the day nearly gone, the hills of Lanark gave back the afterglow of sunset, the whitewashed walls of cottages were pink and old dead grass was the colour of flowering heather.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 50 © Mark Valentine 2016

About the contributor

Mark Valentine and his wife Jo recently spent time on the Isle of Harris, photographing and making notes about that endangered species, the rural postbox.