At school I loved our history lessons. I spent hours drawing plans of castles and battles, and was a binge reader of historical fiction by anyone from Rosemary Sutcliff and Henry Treece to Mary Renault and Robert Graves. A little later I enjoyed exploring first-hand evidence from the past and I particularly remember some volumes in the school library called They Saw It Happen. The third of these English historical anthologies, covering the years 1689–1897, was especially well-known to us because it had been compiled by bufferish Mr Charles-Edwards and suede-shoed Mr Richardson from our very own History Department.

Reading that anthology now I can see how conventional its historical pedagogy was for the 1950s. These eye-witness accounts, while entertaining and informative, read cumulatively like 1066 and All That with a straight face. The two schoolmasters gorge themselves on accounts of British military victories, doings at court and great men, giving only token coverage to such juicy social and political issues as the railways (a Good Thing), radical politics (mobs), empire (heroic) and slavery and child labour (thoroughly Bad Things).

Humphrey Jennings’s anthology of historical witness to English history, Pandaemonium – which existed in typescript years before the third volume of They Saw It Happen appeared – stretches across almost exactly the same period. Yet it is a very different proposition. Jennings has not the slightest interest in the bloody exploits of Marlborough, Anson, Nelson and Wellington, or in the intrigues of Walpole and Disraeli. He focuses instead on what was, for him, the defining driver of change in English destiny: ‘the coming of the machine’.

Jennings was born in 1907, a contemporary of W. H. Auden, John Betjeman, Graham Sutherland, Michael Tippett and Carol Reed. He enjoye

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAt school I loved our history lessons. I spent hours drawing plans of castles and battles, and was a binge reader of historical fiction by anyone from Rosemary Sutcliff and Henry Treece to Mary Renault and Robert Graves. A little later I enjoyed exploring first-hand evidence from the past and I particularly remember some volumes in the school library called They Saw It Happen. The third of these English historical anthologies, covering the years 1689–1897, was especially well-known to us because it had been compiled by bufferish Mr Charles-Edwards and suede-shoed Mr Richardson from our very own History Department.

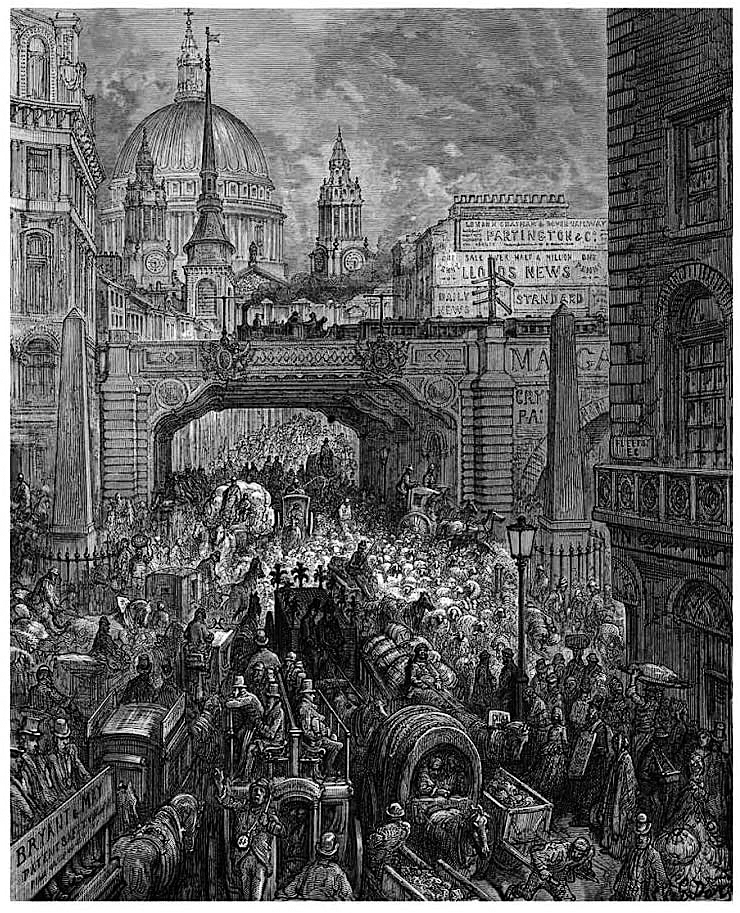

Reading that anthology now I can see how conventional its historical pedagogy was for the 1950s. These eye-witness accounts, while entertaining and informative, read cumulatively like 1066 and All That with a straight face. The two schoolmasters gorge themselves on accounts of British military victories, doings at court and great men, giving only token coverage to such juicy social and political issues as the railways (a Good Thing), radical politics (mobs), empire (heroic) and slavery and child labour (thoroughly Bad Things). Humphrey Jennings’s anthology of historical witness to English history, Pandaemonium – which existed in typescript years before the third volume of They Saw It Happen appeared – stretches across almost exactly the same period. Yet it is a very different proposition. Jennings has not the slightest interest in the bloody exploits of Marlborough, Anson, Nelson and Wellington, or in the intrigues of Walpole and Disraeli. He focuses instead on what was, for him, the defining driver of change in English destiny: ‘the coming of the machine’. Jennings was born in 1907, a contemporary of W. H. Auden, John Betjeman, Graham Sutherland, Michael Tippett and Carol Reed. He enjoyed a meteoric career in the 1930s, hardly straying more than two degrees of separation from the great ones of art – Stravinsky, Picasso, Breton, Magritte, Moore. By the 1930s he had worked as a literary critic, stage designer, documentary photographer and apprentice film director with the esteemed GPO Film Unit. He showed his paintings, published verse, fell in love with surrealism and even slipped for a time into the bed of Peggy Guggenheim (he was notably handsome). In 1936 he became one of the organizers of the ground-breaking International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries and a year later was one of the instigators of Mass Observation, the unprecedented sociological experiment that collected millions of pages of observations from daily life to create ‘the social anthropology of our time’. All these interests fed into his crowning creative achievements, the wartime documentary shorts that included Listen to Britain, Fires Were Started and Diary for Timothy. They also became vital threads in the fabric of Pandaemonium, which by this time he had begun compiling. The opening takes us to Hell, with Milton’s thunderous vision in Paradise Lost of Mammon, the devil who specialized in lucre and material greed, directing gangs of devils as they ‘rifl’d the bowels of their mother earth’ to grub out gold and other precious minerals. These are the raw materials to build Pandaemonium, the capital city of Hell, a colossal monument to wealth, luxury and material vanity. This brilliant opening quotation is followed by Jennings’s note that the building of Pandaemonium ‘began c. 1660. It will never be finished . . . [It] is the real history of Britain for the last three hundred years.’ Jennings, with the practising surrealist’s eye for the unusual, and the film-maker’s delight in intercutting and creative collage, goes on to illustrate how science and technology, once stirred into life around the time of Milton’s epic, began a rolling snowball’s progress that would crush and scatter the remnants of old thinking, and recreate the world in a vast new materialist vein. Jennings’s purpose was to convey the magnificence of it all but also, like Milton extolling the splendours of the satanic city, not to let you forget that this is Hell. The terrible cost of the Industrial Revolution, in ecological damage and human suffering, is never far from his thoughts. There is never an out-season for these matters, but few readers of Pandaemonium will miss their pertinence right now. The story is told in a succession of literary ‘images’ in chronological order and divided into four parts. The first covers the new realism with which writers and intellectuals began to think about Nature and society, as exemplified by one 1660 report to the Royal Society, in a house-style which Jennings glosses as ‘a cold, inch-byinch analysis and reportage of the effects of a thunderstorm, equally without reference to God or man’. In Jennings’s second section, titled ‘Exploitation, 1730–1790’, we read how this new thinking played out in economic terms. There is open-cast and then deep mining, there are scorching ironworks and the first factories and workhouses. This period produced Christopher Smart’s madhouse poetry, a profuse outpouring of imagery dramatizing the very war of materialism against animism, which Jennings saw as a mortal settling of accounts, the death-struggle of the old order. Over it all broods the demon of land enclosure – which we would now call privatization. Great swathes of ancient common land, essential for the subsistence of the rural poor, were being systematically stolen from them, with the dual effect of further enriching the rich, and forcing great numbers of destitute men and women into either industrial work or an eighteenth-century version of the gig economy. This realism extended to a new strain of melancholy pastoral in the arts, developed by poets such as Thomas Gray (a special interest of Jennings) and artists such as George Stubbs (a special interest of mine). Country life was no longer to be imagined as a pleasant, lazy dalliance: it was a matter of toil, overseen by dour taskmasters, and all in the interests of distant landowning plutocrats. The emotional significance of this is underscored by a passage from Oliver Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village:Princes or Lords may flourish or may fade; A breath can make them, as a breath has made; But a bold peasantry, the country’s pride, When once destroyed can never be supply’d.These developments may have been deplored by many in the eighteenth century, but they were rarely seen as resistible. Then a new note is struck: Revolution. Part three of Pandaemonium shows nineteenth-century people fighting back against industrialization – as Thomas Carlyle was the first to call it – with direct action that included inchoate Luddism, agitation for parliamentary reform (as at Peterloo) and Chartism. Eloquent support for these causes came from writers of all sorts. Shelley’s 372-line poem ‘The Mask of Anarchy’, written in whitehot anger at the massacre at Peterloo, and Byron’s sardonic maiden speech in the House of Lords against the bill to make the breaking of machines a capital offence, are two outstanding moments. Others are the German observer Friedrich Engels’s mistakenly optimistic observation of South Lancashire industrially transformed into a perfect seedbed for a new proletarian consciousness; Henry Mayhew’s unique first-hand reports on the lives of the poor; the sanctimonious purblindness of Charles Kingsley (‘Those who live in towns should carefully remember this . . . Never lose an opportunity of seeing something beautiful. Beauty is God’s handwriting’); and Thomas Carlyle’s prophecies ringing with doom – ‘England is dying of inanition.’ In a vivid, barbed description of his visit to the ideal factory-town of Robert Owen in 1819, Robert Southey writes that Owen’s ‘humour, his vanity, his kindliness of nature lead him to make these human machines as he calls them (and literally believes them to be) as happy as he can . . . And he jumps at once to the monstrous conclusion that, because he can do this with 2,210 persons who are totally dependent on him, all mankind might be governed with the same facility.’ William Blake’s is the most remarkable of all these revolutionary voices. If the poem denouncing ‘dark satanic mills’ could hardly have been left out, there are other less familiar Blakean passages here, including a monetized parody of the Lord’s Prayer: ‘Give us day by day our Real Taxed Substantial Money bought Bread; deliver from the Holy Ghost whatever cannot be taxed; for all is debt between Caesar and us and one another; lead us not to read the Bible but let our Bible be Virgil and Shakespeare; and deliver us from Poverty in Jesus, that Evil One.’ The final section of Pandaemonium is titled ‘Confusion’, and begins in 1851. Superficially the confusion is not very apparent. The Pax Victoriana has arrived in all its pomp, railways crisscross the land, whole reaches of the country are given over to factories, the Great Exhibition has opened in the Crystal Palace, and social complacency has set in as firmly as one of Mrs Beeton’s pink blancmanges. The mob, the recurrent cause of societal chaos, has been tamed, and now, in between betting on dogs and racing pigeons, it trots along to the Crystal Palace at a shilling a time to marvel at the wonders of mechanized industry. But for intellectuals there is sickness in the heart of the iron roses that decorate Paxton’s gigantic greenhouse. It is becoming increasingly difficult to square material progress with what has been irreparably lost. John Ruskin glooms over the railway’s destruction of landscape and wonder (‘And now the valley is gone, and the Gods with it, and now every fool in Buxton can be at Bakewell in half an hour’), and two distinctive heirs of Blake, the naturalist Richard Jefferies and the socialist and campaigner for many progressive causes, Edward Carpenter, find life terminally impoverished under, as Carpenter has it, ‘the falsehood of a gorged and satiated society’. Even Charles Darwin rues, and cannot quite account for, the loss of his youthful love of poetry, especially Shakespeare, who now ‘nauseates me’. ‘My mind’, he writes in 1881, ‘seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts’ and adds that ‘the loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness’. Jennings’s closing passage underlines this sense of loss by quoting the last page of William Morris’s A Dream of John Ball. In this novella Morris dreams of meeting John Ball and other heroes of the fourteenth-century Peasants’ Revolt, and absorbs Ball’s mantra that ‘fellowship is life and lack of fellowship is death’. Jennings got from Morris the idea that the machine interferes with human fellowship and, in one of the notes that pepper Pandaemonium’s text, he argues that this is the origin of the Victorian era’s regrettable addiction to sentimentality. ‘Banish human comradeship from life and the naked psyche looks longingly round for an image with which to identify. An image of death and tears and despair: withered grapes, funeral palls or modern machine images, which it can make symbolic of vanished warmth.’ Although there are hopeful passages in this fourth section of the book, Morris’s awakening from his dream is more characteristic of its mood. Jennings might have ended on an up-note by highlighting the quasi-socialist discourse between Morris and Ball, or even with an extract from Morris’s hopeful essay ‘The Factory as It Might Be’. Instead we see the dreamer awakened by dawn ‘hooters’ summoning the factory hands to begin another day at the devil’s work. Humphrey Jennings never saw Pandaemonium in print. He was still collecting material and writing notes for the project in 1950 when, at the age of 43, he fell from a rock while researching a film in Greece, and died from the resulting head injury. The book was assembled and published thirty-five years later by Jennings’s old Mass Observation colleague Charles Madge and his daughter Mary-Lou Jennings. She writes in a preface that her father would quote the French writer Apollinaire’s insistence on the kinship between poetry and history: that only in the past can poets learn imaginatively who they are and what they might become. While some of the ‘images’ in Jennings’s book are indeed fine poetry, most are prose passages. But the final effect is that of a great poetic construction, a tour de force of the imagination. Jennings’s chosen writers do not so much ‘see it happen’ as feel it in their bones.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 67 © Robin Blake 2020

About the contributor

Robin Blake’s sixth mystery novel about eighteenth-century Preston, Death and the Chevalier, was published in 2019.