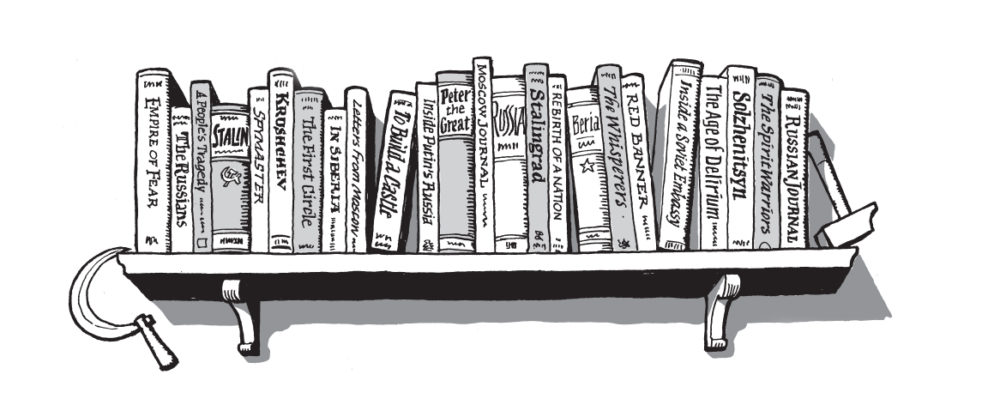

There is a long shelf in our house with 66 books on it. Nothing unusual about that. But every one of these books has a powerful story to tell. Every one contains a memory. They speak to me on those evenings when I relax in a comfortable chair, with music playing in the background, and think back over the past forty years.

You see, all the books on this shelf are about Russia and the Soviet Union. I began collecting them at university but really got into full flow before, during and after a three-year spell in the late 1970s when I lived and worked in Moscow as a foreign correspondent for an American news magazine. A bit of a hiatus ensued after my wife and I left the USSR in 1979, but eventually perestroika prevailed, I resumed visiting what is now Russia in the late 1980s and continued doing so until quite recently – all the while adding to my book collection.

Right at the centre of the shelf are two books that defined my first period in Moscow – The Russians by Hedrick Smith and Russia by Robert Kaiser. Smith worked for the New York Times and Kaiser for the Washington Post, and the two of them were based in the Soviet capital in the same years in the early 1970s. Each day they competed against one another and then, when they left Moscow, they did so all over again through their books. Both were published in 1976, when I was struggling to learn Russian. They remain brilliant evocations of a lost era.

Of the two, Smith’s is livelier and more vivid, Kaiser’s darker and more nuanced. At the time they appeared, people were sharply divided over which one they preferred. Yet even today, more than thirty years later, I can remember the frisson I felt on a beach in Pembrokeshire in the scorching summer of 1976 as I read Smith’s brilliant and affectionate portrait of a people and country kept in thrall by a calamitous political system. Milovan Djilas, the Yugoslav dissident and one-time friend of Tito, d

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThere is a long shelf in our house with 66 books on it. Nothing unusual about that. But every one of these books has a powerful story to tell. Every one contains a memory. They speak to me on those evenings when I relax in a comfortable chair, with music playing in the background, and think back over the past forty years.

You see, all the books on this shelf are about Russia and the Soviet Union. I began collecting them at university but really got into full flow before, during and after a three-year spell in the late 1970s when I lived and worked in Moscow as a foreign correspondent for an American news magazine. A bit of a hiatus ensued after my wife and I left the USSR in 1979, but eventually perestroika prevailed, I resumed visiting what is now Russia in the late 1980s and continued doing so until quite recently – all the while adding to my book collection. Right at the centre of the shelf are two books that defined my first period in Moscow – The Russians by Hedrick Smith and Russia by Robert Kaiser. Smith worked for the New York Times and Kaiser for the Washington Post, and the two of them were based in the Soviet capital in the same years in the early 1970s. Each day they competed against one another and then, when they left Moscow, they did so all over again through their books. Both were published in 1976, when I was struggling to learn Russian. They remain brilliant evocations of a lost era. Of the two, Smith’s is livelier and more vivid, Kaiser’s darker and more nuanced. At the time they appeared, people were sharply divided over which one they preferred. Yet even today, more than thirty years later, I can remember the frisson I felt on a beach in Pembrokeshire in the scorching summer of 1976 as I read Smith’s brilliant and affectionate portrait of a people and country kept in thrall by a calamitous political system. Milovan Djilas, the Yugoslav dissident and one-time friend of Tito, described Smith’s book as ‘the most complex and authentic account [of the Soviet system] that we have had so far’. What a compliment to a foreign correspondent from one of the world’s most acute interpreters of Communism! Smith, like a majority of the authors on my shelf, was writing from the outside at the height of the Cold War. He was no fellow traveller and, of course, he was a foreigner which makes his achievement all the greater. For insider accounts of the last decades of the Soviet era there are no better books than those written by Vladimir Bukovsky (To Build a Castle), Irina Ratushinskaya (Grey is the Colour of Hope and In the Beginning), and Vladimir Petrov (Escape from the Future). Today it is hard to get to grips with the sheer brutality and capriciousness of the Soviet gulag structure, the debasement of law which gave everything a veneer of respectability, and the official lies and deceit which underpinned it all. To measure how far Russia has come today, despite its many ambiguities and failings, books like these four should be reread now and again. They are truly sobering. More recently, Soviet archives have been opened to Western scholars and the result has been a cornucopia of revelations, first-person accounts and bitter exposés. Some of them are magnificent works of literature in their own right. In 1996 Orlando Figes produced his first great work, A People’s Tragedy. After it appeared, no one could be in any doubt about the intrinsic nature of the R Russian Revolution. In this wonderfully written book, Figes managed nothing less than to change the way people thought about Russia and Russians. His second book, The Whisperers (2007), built on this by describing in great detail the private lives of millions of Russians during the Stalinist era. Anne Applebaum’s Gulag (2003) movingly and unsparingly spelled out the existence of the 18 million people who passed through the prison camp network between 1920 and the early 1950s. Anotherbook of this genre well worth reading is Beria, Sergo Beria’s biography of his secret police chief father. Reviewing it for Time in 2001, I argued that it constituted ‘a head-on challenge to the fairy tales which Khrushchev concocted for posterity . . . That said, this remarkable memoir should be approached with care. Beria Jnr never disguises his admiration for his monstrous father.’ Too true. Biographies take up much space on my Russian shelf. Leading the way has to be Michael Scammell’s epic Solzhenitsyn, published in 1984 (there are also several novels by the Russian icon himself on the shelf, including The First Circle). No doubt other writers will revisit Solzhenitsyn in the future. But Scammell’s vast, definitive book (1,050 pages long) remains compelling reading. So does one of the earliest arrivals on my Russian shelf – Edward Crankshaw’s Khrushchev, which was published in 1966 before the maverick Soviet leader produced his own memoirs. Crankshaw was one of the wisest analysts of Soviet affairs in an era when Kremlinology consisted of little more than checking the positioning of leaders’ placards on Leninsky Prospekt. Robert Service’s biography of Stalin also deserves an honourable mention, although recently it has been overtaken by trendier, but not necessarily superior, models. Moving along the shelf I reach a number of oddities – books that only I might wish to read or keep. There is a slender volume by an American Communist called Phillip Bonosky, published in Moscow in 1981 and entitled Are Our Moscow Reporters Giving Us the Facts about the USSR? As this diatribe devotes half a dozen caustic chapters to my reporting from Moscow, it has a special place in my affections. The Moscow Correspondents by Whitman Bassow attempts to strike a better balance. Then there is Letters from Moscow by Jim Weir, the New Zealand ambassador in Moscow when we lived there and a staunch friend when the going got tough. Not many people today will want to read his diary entries but to me they resonate with examples of the small absurdities of life in the Soviet Union circa 1979. Books by friends and colleagues occupy a generous percentage of space on the shelf. Pride of place must go to David Satter’s Age of Delirium. David, an American, and I were contemporaries in Moscow – he represented the Financial Times while I, an Englishman, worked for US News & World Report. This caused no end of problems with the Soviets who had trouble thinking laterally. David left Moscow in 1982 and did not produce his masterpiece until 1996. Most of his friends had long since given up waiting for this cautionary tale of the disintegration of the Soviet system. But in fact the wait was well worth it and now the book ought to be required reading in places like Venezuela and Nepal that are flirting with Marxism. Another colleague in Moscow, Newsweek’s Fred Coleman, also produced a book in 1996 about the collapse of Communism entitled The Decline and Fall of the Soviet Empire. Since I helped to edit this one, perhaps I should declare an interest and leave it to Elena Bonner (Andrei Sakharov’s wife) to give her verdict: ‘Fred Coleman was not afraid to meet with the persecuted and write the truth about them. This is what makes his book significant.’ Russia: Broken Idols, Solemn Dreams by another New York Times alumnus of my era, David Shipler, came out in 1983 and hit the mark with some tremendously detailed case study-type reporting. More personal is Nicholas Daniloff ’s Two Lives, One Russia, written in Vermont in 1988 after Nick, a successor of mine in Moscow, had been arrested by the KGB and subsequently expelled. Other books, too, jump off my shelf. There is, for example, Colin Thubron’s superb travel book In Siberia, almost matched by Philip Marsden’s The Spirit Warriors, Robert Massie’s definitive Peter the Great, Richard Pipes’s riveting historical recreation of the early years of the Soviet era, Russia under the Bolshevik Regime, and Antony Beevor’s Stalingrad – surely one of the best battle books ever written. A specialist work by Christopher Donnelly about the Soviet military system, Red Banner, opens up a closed topic to non-specialists with remarkable facility. Spy books like John Barron’s KGB and Peter Wright’s Spycatcher – purchased in Washington DC in 1987 when it had been banned in the UK – capture the paranoia of the Cold War. Unexpected works by well-known 1940s writers, such as John Steinbeck’s Russian Journal and Harrison Salisbury’s Moscow Journal – both unearthed in obscure second-hand bookshops – are not without merit even today. More recent eye-witness books such as the British Ambassador Roderic Braithwaite’s Across the Moscow River and Andrew Jack’s Inside Putin’s Russia cover the chaotic Yeltsin interlude and the Putin era’s uncomfortably sinister regression. At one time or another many of these books were my travelling companions. I recall especially reading Alan Bullock’s magisterial Hitler and Stalin under an olive tree on a hillside in Tuscany as the Italian lira and the British pound crashed out of the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992. Some still need rather careful scrutiny, like the KGB’s Oleg Kalugin who wrote Spymaster in 1994 apparently with disinformation in mind. Only a few are by women – Irina Ratushinskaya, Elizabeth Pond and Nora Beloff. The last’s effort, No Travel like Russian Travel, is a bit of a curiosity, full of scatty misunderstandings offset by sudden shafts of light. Almost all the books on the shelf retain their original covers, many of them works of art in themselves as designers vied to represent ‘Soviet reality’. Two that stand out are David Satter’s Age of Delirium which has a lowering evening sky highlighting one of the Stalinist skyscrapers that ominously ring central Moscow; and John Lloyd’s Rebirth of a Nation. On the front cover of this book there is a photo of the rebuilt Church of Christ the Saviour under construction in Moscow on a gloomy winter’s day 67 years after the original cathedral was blown up in 1931 on Stalin’s orders. On the back cover there is a statue of Lenin floating down the Danube. Great literature is defined in many ways, and some of these books certainly cross the threshold and qualify for that accolade as well as being valuable studies and compelling, authentic records. Most of the books on my shelf seem to be standing the test of time. A few, inevitably, have already become relics of a bygone age – Inside a Soviet Embassy by Alexander Kaznacheev and Empire of Fear by two Soviet defectors, Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov, spring to mind. But all at one time or another added something to my understanding of Russia and the Russians, and for that I am grateful. Should I be marooned on a desert island and be able to select just one of these books to remind me of my past I would choose Hedrick Smith’s The Russians – for the way it still brings alive Soviet Russia and the Russian people, for its honest reporting, for its fluent writing, for showing me what was possible as a reporter in Cold War Moscow, and for pure enjoyment. What more can you want from a book?Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 25 © Robin Knight 2010

About the contributor

Robin Knight was a news magazine foreign correspondent for 28 years. Between 1976 and 1979 he travelled 50,000 miles in the Soviet Union but still was amazed when Communism collapsed within a decade of his departure. He says there is no connection.