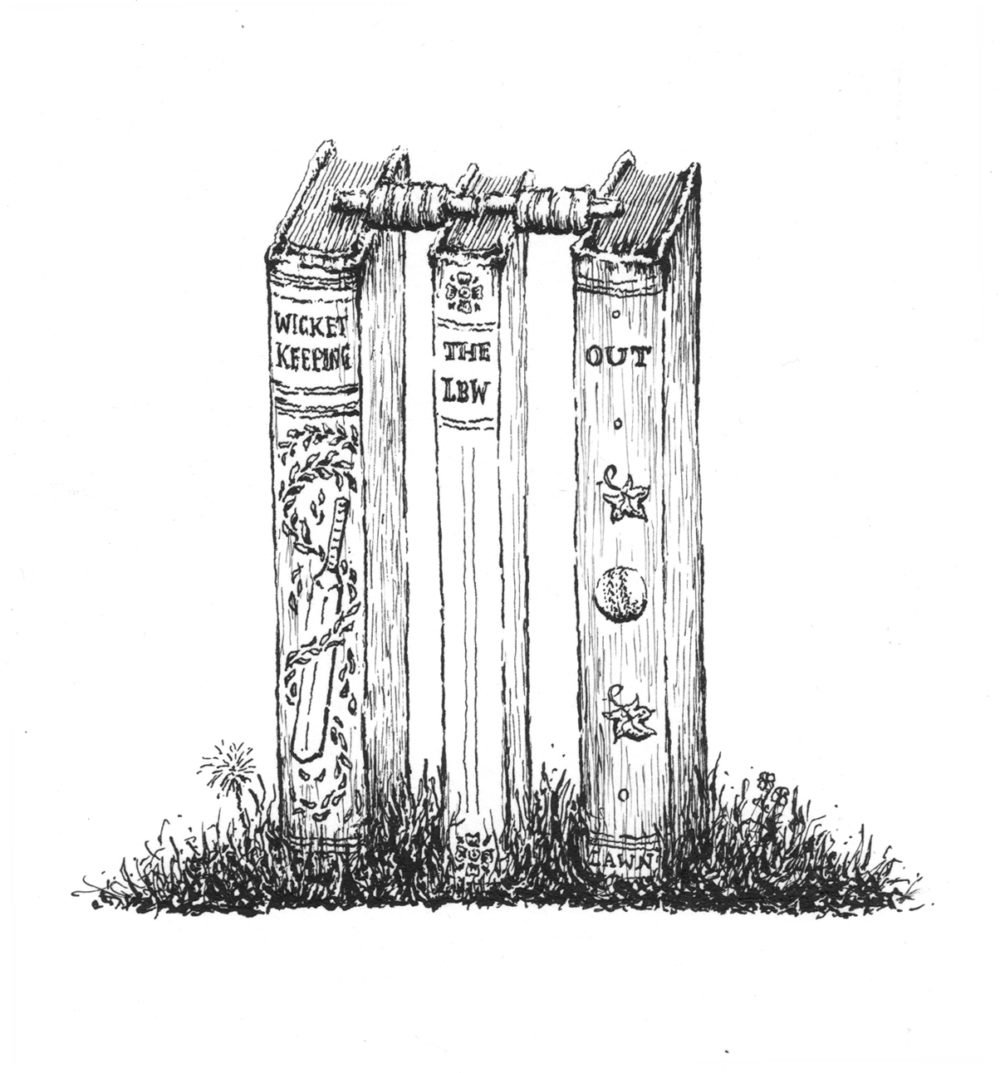

The sound of bat on ball. The smell of newly cut grass. The sight of players in whites crouching, waiting, hoping. Summer must be here. Yet for many cricket lovers there really is no close season. Come autumn, stumps may be drawn but a different type of pleasure replaces the ebb and flow of the physical contest. For the true enthusiast, those shelves stacked with old and (occasionally) new books on the game serve as the perfect antidote to winter.

No other sport can boast such a rich literature. Opinions vary as to whether cricket is an art form or not. But without doubt its leading practitioners deserve to be read widely, regardless of affection for the game. ‘Flight was his secret, flight and the curving line, now higher, now lower; tempting; inimical; every ball like every other ball, yet somehow unlike; each over in collusion with the others, part of a plot.’ So Neville Cardus wrote of the great Yorkshire slow bowler Wilfred Rhodes in Autobiography (1947). ‘Every ball a decoy, sent out to get the lie of the land; some balls simple, some complex, some easy, some difficult; and one of them – ah, which? – the master ball.’ Magic!

My modest library is full of books on cricket – at least 500 of them – yet I can date the start of this collection with precision to the 1953 edition of the cricketer’s bible Wisden. It was my tenth birthday that June and I was already hooked on the game, so my parents responded by giving me this amazing window on to the adult world. Pencilled schoolboy comments litter its 1,015 pages. The spine is faded and the gold lettering on the brown cover is hard to decipher now. But what riches are to be found inside – a fine celebratory essay on the fast bowler Alec Bedser, an evocative advertisement for Brylcreem featuring the incomparable Denis Compton, a profile of fiery Fred Trueman, batting and bowling averages galore.

English cricket, and life, in 1952 (the year under review) was sharply

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe sound of bat on ball. The smell of newly cut grass. The sight of players in whites crouching, waiting, hoping. Summer must be here. Yet for many cricket lovers there really is no close season. Come autumn, stumps may be drawn but a different type of pleasure replaces the ebb and flow of the physical contest. For the true enthusiast, those shelves stacked with old and (occasionally) new books on the game serve as the perfect antidote to winter.

No other sport can boast such a rich literature. Opinions vary as to whether cricket is an art form or not. But without doubt its leading practitioners deserve to be read widely, regardless of affection for the game. ‘Flight was his secret, flight and the curving line, now higher, now lower; tempting; inimical; every ball like every other ball, yet somehow unlike; each over in collusion with the others, part of a plot.’ So Neville Cardus wrote of the great Yorkshire slow bowler Wilfred Rhodes in Autobiography (1947). ‘Every ball a decoy, sent out to get the lie of the land; some balls simple, some complex, some easy, some difficult; and one of them – ah, which? – the master ball.’ Magic! My modest library is full of books on cricket – at least 500 of them – yet I can date the start of this collection with precision to the 1953 edition of the cricketer’s bible Wisden. It was my tenth birthday that June and I was already hooked on the game, so my parents responded by giving me this amazing window on to the adult world. Pencilled schoolboy comments litter its 1,015 pages. The spine is faded and the gold lettering on the brown cover is hard to decipher now. But what riches are to be found inside – a fine celebratory essay on the fast bowler Alec Bedser, an evocative advertisement for Brylcreem featuring the incomparable Denis Compton, a profile of fiery Fred Trueman, batting and bowling averages galore. English cricket, and life, in 1952 (the year under review) was sharply structured so no less than 88 pages are devoted to university and public school cricket. As always with Wisden, there is room for the offbeat and quirky. On p. 671 we discover that a New Year’s Day match was played in Edinburgh in 1953. Lunch consisted of Scotch broth, haggis with neeps and mash, and whisky. Another entry reveals that eighteenth-century players wore ‘three-cornered or jockey hats, often with silver or gold lace’. In the obituaries section we learn that King George VI, as a prince, performed the hat trick (three wickets in three balls) when bowling on a ground below Windsor Castle. Addicted to the game, I quickly became addicted to its literature. Today Wisdens stretch out for yards on the shelves in our house. Not a full collection of 147, but nearly so; I have resisted (so far) paying £6,000 for the earliest edition published in 1864. It was the 1953 Wisden which introduced me to Cardus. Today, almost forty years after he died, he remains the gold standard against which cricket writing in English is judged, not for his command of facts (always shaky) but for his command of language and imagination – in the words of the radio commentator John Arlott ‘the first writer to evoke cricket; to create a mythology out of the folk hero player – essentially to put the feelings of ordinary cricket watchers into words’. How to convey these qualities succinctly? Close of Play, published in 1956, is one of more than fifteen books Cardus wrote on cricket. At the time, aged 67, he was contemplating retirement from writing about the game in order to devote his energies to music criticism. The result was an unashamedly nostalgic work, full of acute observation, juicy anecdotes and sharp commentary. And some memorable phrase-making: ‘His hatchet face and his hint of a physical leanness and an unsentimental mind were part and parcel of his cricket’; ‘The imagination yawns like a cavern of tedium’; ‘He became patience on a pedestal of modern concrete.’ As J. B. Priestley remarked, Cardus was ‘a superb all-round writer’. Rivals trailed in his wake for decades. Recently, however, two outstanding newcomers have popped up – Iain Wilton and Duncan Hamilton. Both have demonstrated the lasting appeal of good biography. That both focus on cricketers is incidental. Wilton’s substantive C. B. Fry: An English Hero appeared in 1999 and was an immediate success – a classic biography based on good detective work, balanced analysis and lively writing. That Fry was controversial throughout his life (he was born in 1872 and died in 1956) helped; it must be purgatory to give up a job (as Wilton did), spend years on research and unearth a boring character. Wilton’s great skill was to put the successes and failures of this complex, garrulous all-rounder into context and to do so with style and panache. This achievement was matched a decade later by Duncan Hamilton with his book Harold Larwood. This biography won the author the 2009 Sports Book of the Year only two years after his first attempt at the genre (on football manager Brian Clough) won the same award. Harold Larwood is nothing less than a literary tour de force – a model for any biographer. Larwood, the Nottinghamshire-born, fast-bowling, working-class hero or villain of the infamous 1932–3 Bodyline series between Australia and England, had been profiled many times before. Hamilton manages to take the story to another level through the clarity and flow of his prose, his research and his trenchant analysis of 1930s English society. And he can write. How about this on Larwood recuperating at the end of a long English season en route by boat to Australia: ‘He’d think about the chop of a sea so intensely blue it hurt your eyes to look at it, and the way in which the sun prickled your skin and regenerated your spirits so much that you soon forgot about the rain in England, the drabness of your own country.’ Still, for cerebral qualities in a book with cricket as its theme there is really only one contender – The Art of Captaincy by Mike Brearley. It was published in 1985 and I see I have inscribed my copy ‘purchased at Heathrow en route to cover a Mideast hijack’ – very apt, given the way it dissects extremes of human behaviour with a scalpel. Brearley, of course, is not just a well-regarded former captain of the England cricket team but also a renowned psychoanalyst and psychotherapist with a double first from Cambridge in Classics and Philosophy. It is a lethal combination. He wrote the book, he confides, as ‘a bridge between one career and another’ and it took four years to complete. So it is far removed from the forgettable instant histories favoured by too many retired players (and publishers). Instead what you get is a clinical dissection of leadership and motivation. What makes it so readable and fascinating is the insights it offers (supported by copious examples of real events) into cricketers’ mental processes – the place of aggression in the game, the importance of memory, the balance between orthodoxy and experiment, and so on. Paragraphs pose and juxtapose propositions one after the other in true therapist style. Typically, Brearley wanted his book to provoke as well as to entertain. At one point he memorably combines his intellectual and sporting disciplines when explaining why not every professional cricketer might wish to wear a helmet when batting. ‘In the company of starving people, it is indecent to complain that one’s steak is underdone. If the Greeks had had to play cricket under the walls of Troy, Agamemnon might well have unbuttoned his breastplate and doffed his helmet, however rough the pitch.’ ‘Games, like art, achieve their impact in the way they reflect and symbolize life outside the frame, the stage, the arena. Of all games, cricket embodies life’s passions most richly,’ Brearley asserts. It is a claim explored in depth in Beyond a Boundary written by the West Indian Marxist C. L. R. James in the early 1960s. To James, there is no doubt. Cricket is an art – ‘a dramatic spectacle that belongs with the theatre, ballet, opera and dance – visually powerful, beautiful to watch’. He adds magisterially: ‘We may some day be able to answer Tolstoy’s exasperated and exasperating question: What is art? – but only when we learn to integrate our vision of Walcott [the West Indies batsman] on the back foot [hitting] through the covers.’ As this quotation indicates, Beyond a Boundary stretches the definition of a ‘cricket book’ to the limit. James was a black political activist and intellectual, as well as a lifelong cricket devotee and a well-known author and journalist. He spent his adult existence fighting the class war, racism and colonialism. No one who has ever written at any length about the game has managed to place it more deeply in its social context – in this case, via the centrality he asserts for cricket in creating and moulding the values, attitudes and cultures of the diverse societies and peoples who inhabit the islands of the Caribbean. ‘Cricket had plunged me into politics long before I was aware of it,’ James notes almost in passing. ‘When I did turn to politics I did not have too much to learn.’ Beyond a Boundary has an intrinsic quality that is sufficient to arouse interest well beyond the cricket world. My copy was published in the US in 1983 and begins with ‘A Note on Cricket’ for its American audience. Such is the book’s wide appeal. But no one would describe it as having been written for the masses. Indeed, some have denigrated it by arguing that it is ‘difficult to read’. Maybe true – but it explores profound and enduring social and political themes around a single question: ‘What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?’ If there is one episode in the book worth sharing it must be James’s description of the contortions he went through before deciding to play for one club side rather than another in his native Trinidad in the 1920s. Every kind of racial and class distinction of the time was involved. One club was for the brown middle class, another for black ‘plebeians’ such as butchers. A third for the white ruling caste. A fourth for the constabulary. A fifth for Roman Catholics. Yet with one exception all these sides played on the same field and got along perfectly well. It is a brilliant vignette made sharper by the revelation that James allowed himself to be talked into joining the ‘wrong’ club, so cutting himself off from ‘the popular side, delaying my political development for years’. And you thought cricket was just about boring old batting and bowling! It may be trite to argue that sport mirrors life but where cricket is concerned surely it does – in all its complexities. As Duncan Hamilton, a book collector himself, reflects in Harold Larwood, ‘part of the reason there is so much good cricket literature, and why it endures on the shelf, is because of the flow of the game and the surroundings in which it is set. Place is very important in cricket.’Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 39 © Robin Knight 2013

About the contributor

Robin Knight was a foreign correspondent for nearly 30 years. His memoir A Road Less Travelled was published in 2011. Sales have been good but he is hoping for more. Further details appear on www.knightwrite.co.uk.