Up the stairs past the coloured 1850s lithographs of British sportsmen pig-sticking in India; into the room with the campaign chest and Grandfather’s medals on top, their clasps with names like Waziristan and Chitral, and the picture of the General, his half-brother, a Mutiny hero who eventually expired of apoplexy on the parade ground at Poona. There was no escaping the Raj – witness the fact that my first job when I joined John Murray in 1972 was to superintend an update of their Handbook to India.

In 1988 a typescript arrived at Murray’s from the elderly Janet Dunbar, a stalwart of the BBC in her time. It turned out to be a transcript of some illustrated journals kept in India by Fanny Eden while accompanying her brother George, Lord Auckland, the Governor-General from 1836 to 1842. They were lively, perceptive, full of shrewd irony, and worth publishing, but their editing and transcription left a lot to be desired. So off I went to the India Office Library to check with the originals, and for background I read Up the Country by Fanny’s sister Emily, covering the same period and events, since she was also out there with brother George.

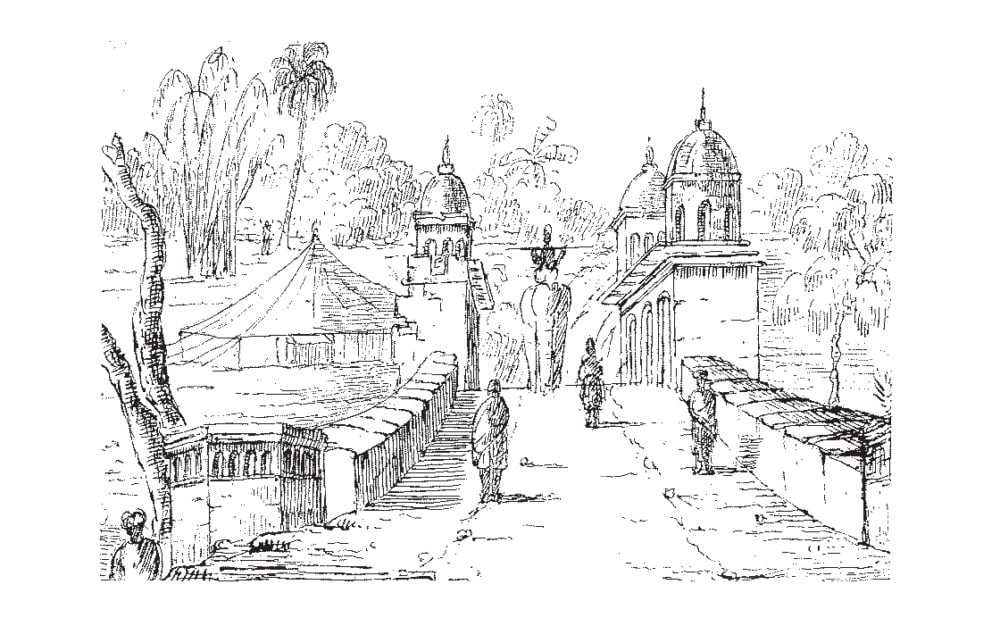

Up the Country had been published in 1866 with the subtitle ‘Letters written to her sister [another one back in England] from the Upper Provinces of India’. It gives a clue to the book’s subject – a journey out of Bengal following the Ganges beyond Benares towards Delhi. This is what the unmarried George did in 1837, accompanied by his youngest sisters Emily and Fanny, an entourage of 12,000, plus 140 elephants, 850 camels and innumerable bullocks and horses, only returning to Calcutta two and a half years later. The main object was for George to cement the treaty of friendship signed by his predecessor with Ranjit Singh, the ‘Lion of the Punjab’ and mighty King of the Sikhs, by paying him a state visit. He, it was hoped, would be so impressed by ‘the clinquant

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inUp the stairs past the coloured 1850s lithographs of British sportsmen pig-sticking in India; into the room with the campaign chest and Grandfather’s medals on top, their clasps with names like Waziristan and Chitral, and the picture of the General, his half-brother, a Mutiny hero who eventually expired of apoplexy on the parade ground at Poona. There was no escaping the Raj – witness the fact that my first job when I joined John Murray in 1972 was to superintend an update of their Handbook to India.

In 1988 a typescript arrived at Murray’s from the elderly Janet Dunbar, a stalwart of the BBC in her time. It turned out to be a transcript of some illustrated journals kept in India by Fanny Eden while accompanying her brother George, Lord Auckland, the Governor-General from 1836 to 1842. They were lively, perceptive, full of shrewd irony, and worth publishing, but their editing and transcription left a lot to be desired. So off I went to the India Office Library to check with the originals, and for background I read Up the Country by Fanny’s sister Emily, covering the same period and events, since she was also out there with brother George. Up the Country had been published in 1866 with the subtitle ‘Letters written to her sister [another one back in England] from the Upper Provinces of India’. It gives a clue to the book’s subject – a journey out of Bengal following the Ganges beyond Benares towards Delhi. This is what the unmarried George did in 1837, accompanied by his youngest sisters Emily and Fanny, an entourage of 12,000, plus 140 elephants, 850 camels and innumerable bullocks and horses, only returning to Calcutta two and a half years later. The main object was for George to cement the treaty of friendship signed by his predecessor with Ranjit Singh, the ‘Lion of the Punjab’ and mighty King of the Sikhs, by paying him a state visit. He, it was hoped, would be so impressed by ‘the clinquant figure of his Excellency’ and the ‘two interesting females caracoling on their elephants on each side of him’, as Fanny put it, that he would fall in with whatever plans Britain had for him. At the same time George could inspect the Upper Provinces and they could avoid the worst of the summer heat by retreating to Simla in the foothills of the Himalayas. Emily Eden was born in 1797, Fanny in 1801, the youngest of 14 children. Their father was a politician and diplomat while their mother, whose brother Lord Minto had been Governor-General from 1807 to 1813, was nicknamed the Judicious Hooker because of her skill at marrying off her daughters, though the expected match of one sister to Pitt the Younger did not materialize and she was dead before she could find husbands for the youngest two. Emily’s, Fanny’s and George’s natural habitats were the great Whig country houses such as Woburn, Chatsworth and Bowood, and it was the Whigs’ eventual return to power in the early 1830s that resulted in George being offered the Governor-Generalship. The sisters had all the patrician self-assurance of such a background, together with a Whig hatred of injustice to individuals. Evangelical fervour or a sense of imperial mission, so often to bear poisoned fruit as the century wore on, were no part of their makeup. They may have made little effort to master any Indian language and shown limited interest in Indian customs, culture or religion, but neither did they condescend to Indians. For Emily, ‘the Hindu religion has two merits – constant ablution, and the sacredness of their trees’. As for the Muslims, she felt ‘there is nothing absurd or revolting about their religion; it is only incomplete’. Emily’s book has all the same qualities as Fanny’s. The two of them turn a sharp, amused, Austenesque gaze on everything as they ‘stroll about on an elephant’, in Fanny’s phrase. They never cease to be amazed by the presence of the British in India in the first place – as Emily put it, ‘How people who might, by economy and taking in washing and plain work, have a comfortable back attic in the neighbourhood of Manchester Square, with a fireplace and a boarded floor, can come and march about India, I cannot guess.’ It is the combination of their amused, quizzical outlook with both the exotic, often excessive, sometimes barbaric, sometimes greatly refined worlds of Benares, Lucknow, Delhi, the court of Ranjit Singh or Agra, and the various British stations, unrelenting in their efforts to keep up the English way of life, that makes their letter-journals both so compelling and so entertaining. They were glad to leave Calcutta in October 1837, where the temperature reached 105 degrees in the shade before the breaking of the monsoon, causing furniture to crack ‘in all directions’ and horses to die waiting for their owners to emerge from church. The first stage of the tour was in houseboats drawn by steamers up-river to Benares, the view from them of ‘the most picturesque population, with the ugliest scenery, that was ever put together’. An on-board compensation was being able to read the parts of Pickwick Papers in the right order, all at once. At Benares, the routine began of camping interspersed with daily marches averaging ten miles, together with durbars for local princes, entertainments by their nautch dancers and the exchange of presents. The marches began at five or six in the morning to avoid the heat of the day, with the head of the cavalcade often reaching the next campsite before the tail had left the old one. The business of presents was complicated: there was a strict rule that those received had to be handed over to a special government official in the party, who was always anxious lest they might not be worth as much as the ones which the British party had to give in return. The climax of these exchanges came at the Rajah of Gwalior’s durbar, when his new 8-year-old wife loaded the two sisters with diamond necklaces and bracelets, pearl earrings hanging nearly to the waist and immense diamond tiaras, as well as a bale of shawls. ‘We must have looked like mad tragedy queens . . . and there was George, sitting bolt upright, a pattern of patience, with a string of pearls as big as peas round his neck, a diamond ring on one hand, and a large sapphire on the other, and a cocked hat embroidered in pearls by his side.’ When the Rajah paid his return visit the next day, the problem of what to give him was solved by presenting him with ‘a shawl tent with silver poles that Ranjit gave us [earlier in the trip] and in that was the gold bed inlaid with rubies, also Ranjit’s’. At Lucknow, the capital of Oudh, there was a visit to see the Thugs in prison. These were men who earned their living murdering travellers, the technique being handed down from one generation to the next. It was acted out for the visitors, with the victim invited to sit down and smoke and then have a bird or the sun pointed out to him: ‘when the traveller looked up a noose was round his neck in an instant’, and he would have been buried within five minutes in a grave already dug. In Delhi Emily found the palace of the descendant of the Mogul emperors a melancholy sight, surrounded by a garden ‘all gone to decay’. The inlaid floors were ‘constantly stolen, and in some of the finest baths there were dirty [beds] spread, with dirtier guards sleeping on them. In short, Delhi is a very suggestive and moralizing place . . . Somehow I feel we horrid English have . . . merchandised it, revenued it, and spoiled it all. I am not very fond of Englishmen out of their own country.’ Emily’s mood of disenchantment continued on the last stages before they reached the refuge of Simla, where they could stop marching and live in a house with surrounding vegetation, and hilly vistas. ‘Never was there such delicious weather, just like Mr Woodhouse’s gruel [in Emma], “cool, but not too cool”.’ Once they had recruited their strength in the hills, they were ready to face their biggest challenge, the visit to Ranjit Singh. Emily, an accomplished artist, had the important job of painting a picture of the new Queen Victoria, merely from the descriptions of her in the papers, to give to the King. He was delighted with it and it was given a 21-gun salute. She described him as ‘exactly like an old mouse, with grey whiskers and one eye’, and ‘a very drunken old profligate, neither more nor less. Still he has made himself a great king.’ The costumes, jewellery and entertainments at his court were an Arabian Nights fantasy, culminating in the parade of his stud, where one horse had trappings largely made of huge emeralds, another of diamonds and turquoises, another of pearls and coral. Mission apparently accomplished, it was back to Simla and the high point of the ball in honour of Queen Victoria in May 1839. ‘Twenty years ago no Europeans had ever been here, and there we were, with the band playing the “Puritani” and “Masaniello”, and eating salmon from Scotland and sardines from the Mediterranean.’ Emily had prophesied that when Ranjit died, his great kingdom, ‘which he has raked together, will probably fall to pieces again’. And when this indeed happened that year the disintegration was swift, as one ruler followed another, and their wives and slave girls processed to their funeral pyres, there to be burnt alive with their dead masters. In a desperate attempt to bring unity to their country the Sikhs were to invade British territory in 1845; by 1849 the Sikh Empire had been absorbed into the British. In October 1839 the Edens started out for Calcutta, reaching there in March 1840. They had another two years before they finally sailed for England, but Emily’s journals stop at that point – Fanny’s finish at the start of 1839. George’s term of office was to end tragically because he, like others who followed him, took the wrong advice over Afghanistan. He was told he should supplant its ruler, who was suspected of falling under the influence of the Russians. Ranjit Singh was eager for this and the British thought it was the Sikhs who would engineer the switch of rulers. In negotiation, Ranjit ran rings round them and, lo and behold, it was a British army that marched to its fate through the Khyber Pass, ending up massacred almost to the last man early in 1842, largely through the incompetence of its commanders. One can only imagine the anguish of the Edens on the long voyage home with this uppermost in their minds. However, once back, Emily was soon striking the old note: ‘I am getting on very well with England, thank you; fine climate, good roads, fair-complexioned people, language not difficult, costume rather unbecoming, but probably adapted to the feelings and wants of the natives; in short it all does very well.’ Both Fanny and George were to die in 1849, but Emily survived until 1869, publishing two novels, The Semi-Detached House and The Semi-Attached Couple, both regularly reprinted like Up the Country, appealing as they do to anyone partial to a strong flavour of Austen in their reading.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 30 © Roger Hudson 2011

About the contributor

After editing Fanny Eden’s journals roger hudson found himself making a selection from William Hickey’s largely Indian memoirs, and then compiling The Raj: An Eyewitness History of the British in India, both for the Folio Society.