The Folio Society was founded 65 years ago and has been gradually undergoing apotheosis into a National Treasure, to join Radio 4, the Proms, Alan Bennett and the London taxi. Like some hound of heaven, it is in unrelenting pursuit of quality, its books by the best authors old and new produced using the best methods old and new, and new illustrators too, striving to end up with the best that mind, hand and eye can do.

It is not surprising that members of Folio and subscribers to Slightly Foxed are quite often one and the same. Those for whom reading is an important part of life may well hanker after something more in the way of the book beautiful than an airport bookstall or the stickered stacks of three-for-two can offer. Not always, you understand: the motives of someone who only has Folio books on view might be suspect. Have they been bought as a short cut to cultivation, for display only? But for inveterate spine scanners who convince themselves that books are an indicator of character, it is always reassuring to spot some Folio titles mixed in on a person’s shelves, to know he or she has succumbed to their tactile and visual pleasures – the beautifully engineered slipcases, the proper cloth or buckram bindings, the paper that remains unfaded, the well-chosen typefaces, the attention to proportion and space. There is anticipatory pleasure reading the litany of specifications in each year’s catalogue: ‘Quarter-bound cloth with Modigliani paper sides’, ‘Bound in blocked buckram’, ‘Set in Bembo, in Adobe Caslon, in Palatino’, even ‘in Elysium with Clairvaux display’. It is like going to bed with an Elizabeth David cook book after dining off baked beans (four-volume boxed set, yours for £19.95 from Folio, as an introductory offer).

And then there are the pictures, and the designs on the bindings. Some people are snooty about illustrating grown-up fiction, vapouring on about how their imaginations will generate all the ima

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe Folio Society was founded 65 years ago and has been gradually undergoing apotheosis into a National Treasure, to join Radio 4, the Proms, Alan Bennett and the London taxi. Like some hound of heaven, it is in unrelenting pursuit of quality, its books by the best authors old and new produced using the best methods old and new, and new illustrators too, striving to end up with the best that mind, hand and eye can do.

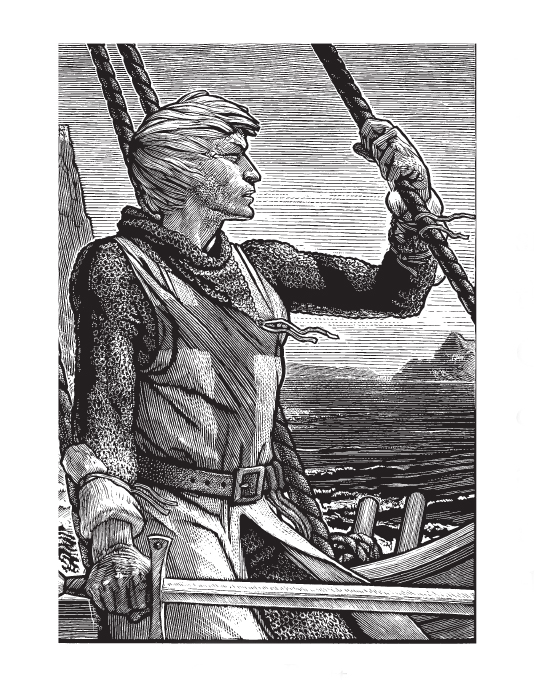

It is not surprising that members of Folio and subscribers to Slightly Foxed are quite often one and the same. Those for whom reading is an important part of life may well hanker after something more in the way of the book beautiful than an airport bookstall or the stickered stacks of three-for-two can offer. Not always, you understand: the motives of someone who only has Folio books on view might be suspect. Have they been bought as a short cut to cultivation, for display only? But for inveterate spine scanners who convince themselves that books are an indicator of character, it is always reassuring to spot some Folio titles mixed in on a person’s shelves, to know he or she has succumbed to their tactile and visual pleasures – the beautifully engineered slipcases, the proper cloth or buckram bindings, the paper that remains unfaded, the well-chosen typefaces, the attention to proportion and space. There is anticipatory pleasure reading the litany of specifications in each year’s catalogue: ‘Quarter-bound cloth with Modigliani paper sides’, ‘Bound in blocked buckram’, ‘Set in Bembo, in Adobe Caslon, in Palatino’, even ‘in Elysium with Clairvaux display’. It is like going to bed with an Elizabeth David cook book after dining off baked beans (four-volume boxed set, yours for £19.95 from Folio, as an introductory offer). And then there are the pictures, and the designs on the bindings. Some people are snooty about illustrating grown-up fiction, vapouring on about how their imaginations will generate all the images they need. The riposte to that is Dickens and Phiz, Surtees and Leech, Sherlock Holmes and Sidney Paget. In the past Folio has added to this roll of honour with such achievements as Joan Hassall’s wood engravings for Jane Austen, Simon Brett’s for a gamut running from Keats and Shelley to Legends of the Grail, Charles Keeping’s drawings for the 16-volume Dickens, Edward Bawden’s linocuts for Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. Folio threw a lifeline to illustrators as work for advertisers and magazines began to dry up from the 1950s, and it continues to be the one firm regularly commissioning pictures for something other than children’s books. The chances it offers young artists who have managed to survive the near-death in art schools of academic drawing and the bias towards the non-representational, if not the downright conceptual, are beyond price. Current and recent Folio lists are testimony to how these chances have been seized. Take for example Anna Bhushan’s drawings for The Bhagavad Gita, Michael Kirkham’s for Of Human Bondage or Matthew Richardson’s collage images for Albert Camus’ The Outsider. The latter was the winner of the inaugural Book Illustration Competition run jointly by Folio and the House of Illustration and has now won one of the 2012 V&A Illustration Awards for its cover. Any idea that Folio is wedded to the representational or conventional – except of course for non-fiction and history, where period pictures and photographs are the norm – will quickly be dispelled by a look at the current catalogue or website. There too the bindings for Clausewitz’s On War and for G. E. R. Lloyd’s Greek Science show what can be done with pattern and symbol to capture the overall theme of a book. There is something of the Apostolic Succession, of passing on the sacred flame, about the origins of the Folio Society. The Golden Cockerel Press had been perhaps the most distinguished of the inter-war private presses, and Christopher Sandford, one of the three founders of Folio, owned it in 1947. Not only that, but Folio began life sharing the Golden Cockerel offices in Soho. And it has recently reissued The Four Gospels, The Canterbury Tales and Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde in facsimile which, with their Eric Gill illustrations, many consider to be the Golden Cockerel at its best. The other Folio founders were Alan Bott, who had already created the Book Society and the paperback imprint Pan Books, so could bring book trade expertise, and Charles Ede whose idea it was. Ede claimed he could only bring enthusiasm, though in fact he ran the show, giving the firm much of its ethos and flavour. They had to cope with paper rationing but post-war there were many who felt starved of quality and were longing for anything that tried to raise standards above the ‘utility’ norm. In retrospect Folio can be seen as part of a high-minded Welfare-Stateism signalled by the founding of the Arts Council and the BBC Third Programme and culminating in the 1951 Festival of Britain. To begin with the books were sold via bookshops, but this did not work and it was only when members started to be recruited directly through press advertising in 1949–50, and were offered a incentive in the form of a free ‘presentation volume’, that things started to look up. The deal was much the same as today: you were asked to commit to taking four books a year. Early titles had jackets but the first slipcase came in 1954; almost from the start introductions were specially commissioned for virtually all books. The Society could not afford to gamble so stuck almost entirely to classic fiction and poetry, but gradually history and ancient history, travel and biography, humour, children’s books and modern fiction were added to the mix, and boxed sets were produced as well as individual volumes. Conventional publishers have always envied Folio for being able to sound out its membership about what future choices it favoured; what’s more, it could then establish a reasonably accurate number to print by getting advance orders once the yearly catalogue had been mailed out. They also used to assume that it could afford better production standards because it paid so little in royalties, since most of its books were old enough to be out of copyright. With more and more twentiethcentury authors and recent translations of foreign-language titles, this has long ceased to be the case. Charles Ede said he only wanted to work in a business where he could do everything himself, so in 1971 he gave up Folio and instead became a leading dealer in classical antiquities. One of the most noticeable trends over the next two decades was the move into history, which for years has been the Society’s biggest-selling category. This produced a number of books in which Folio’s editorial input was greatly increased: selecting material from different sources, ordering it, writing linking passages. A prime example was Macaulay’s History of England, where his original volumes covering 1685 to 1702 were extended backwards and forwards in time by Peter Rowland, using Macaulay’s essays and articles. Here I must declare a bias, because I compiled quite a number of such books for the Society, making a selection for the series called ‘Eighteenth-century Memoirs’ from the original four volumes of William Hickey’s, which was illustrated by the wonderful John Lawrence and bound using Ann Muir’s marbled paper; then selections from the journalism of the great war reporter William Howard Russell and from the copious literature of the British in India, for the ‘Epics of Empire and Exploration’ series, with brilliant pastiche Victorian blocked bindings by David Eccles. I was also let loose on Queen Victoria’s Jubilee years, the English Civil War through women’s eyes and the Grand Tour. What might be termed the Gavron effect started kicking in at the end of the 1980s. Bob Gavron, creator of the St Ives printing group, had bought Folio in 1982, and he was responsible for its major expansion. There were years when membership was well over 100,000 and the number of new editions over 80 (in 1987 the figures had been 36,000 and 25). The task of maintaining production standards under this pressure while absorbing the impact and possibilities of computerization and constantly refreshing the reservoir of artists fell to Joe Whitlock Blundell, who had arrived in 1986. As well as overseeing such enterprises as the 47-volume complete Trollope, the facsimiles of great late Victorian or Edwardian children’s books illustrated by the likes of the Detmold brothers and Arthur Rackham, and Andrew Lang’s Rainbow Fairy Books, Joe has also been behind the remarkable series of limited editions which have added another dimension to Folio: the William Blake Night Thoughts, with Gray’s Poems to come, reproducing his illustrations never published in his lifetime and subsequently scattered round the world’s museums, just as was done in Folio’s earlier Blake Inferno and Paradise Lost ; the ongoing Letterpress Shakespeare and the King James Version of the Bible, both uncluttered and eminently readable; medieval facsimiles such as the Hereford Mappa Mundi, its colouring restored, the Fitzwilliam Book of Hours, The Luttrell Psalter and a poignant modern one, The South Polar Times by the men of Scott’s two expeditions, published on the centenary of his death last year. With its membership somewhere a little below 100,000 now, about equally divided between Britain and North America, and the number of new editions around 60 a year plus some limited editions, the Folio Society must be well placed to benefit from the advent of the e-book. It can become one of the best comforts and recourses, not merely for those in (one hopes, irrational) dread of some bookless dystopia, along the lines of that in Fahrenheit 451 (Folio edition, December 2011), but also for the many who have become accustomed to the screen but want a regular treat, a reminder of the best of what reading can be.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 37 © Roger Hudson 2013

About the contributor

Roger Hudson compiled, selected or edited over a dozen books for Folio while also working for a number of other publishers, including his old firm, John Murray.

The Folio Society is at 44 Eagle Street, London WC1R 4SF, telephone 020 7400 4200. Its website is at www.foliosociety.com. The illustrations in this article have been substantially reduced in size from the originals.