Shortly after the end of the Second World War, the Royal Society of Literature took out a long lease on a white stucco Bayswater house, formerly the home of General Sir Ian Hamilton, leader of the Gallipoli Expedition. It was dilapidated but spacious, and a first-floor room roughly the size and shape of a tennis court became a library in which the Society’s Fellows could browse among one another’s works. All went well until, in the early Seventies, an elderly, light-fingered Fellow took to leaving the building with volumes secreted between two pairs of trousers, which he wore sewn together at the hem. The library was closed.

I began working for the Royal Society of Literature in the autumn of 1991, and it was on the shelves of this silent, abandoned room that I first discovered Akenfield: Portrait of an English Village. Published in 1969, it had become an instant classic, and, since then, it has never been out of print. From the first sentence – ‘The village lies folded away in one of the shadow valleys which dip into the East Anglian coastal plain’ – it was clear that this was a book to slow down for, and to relish.

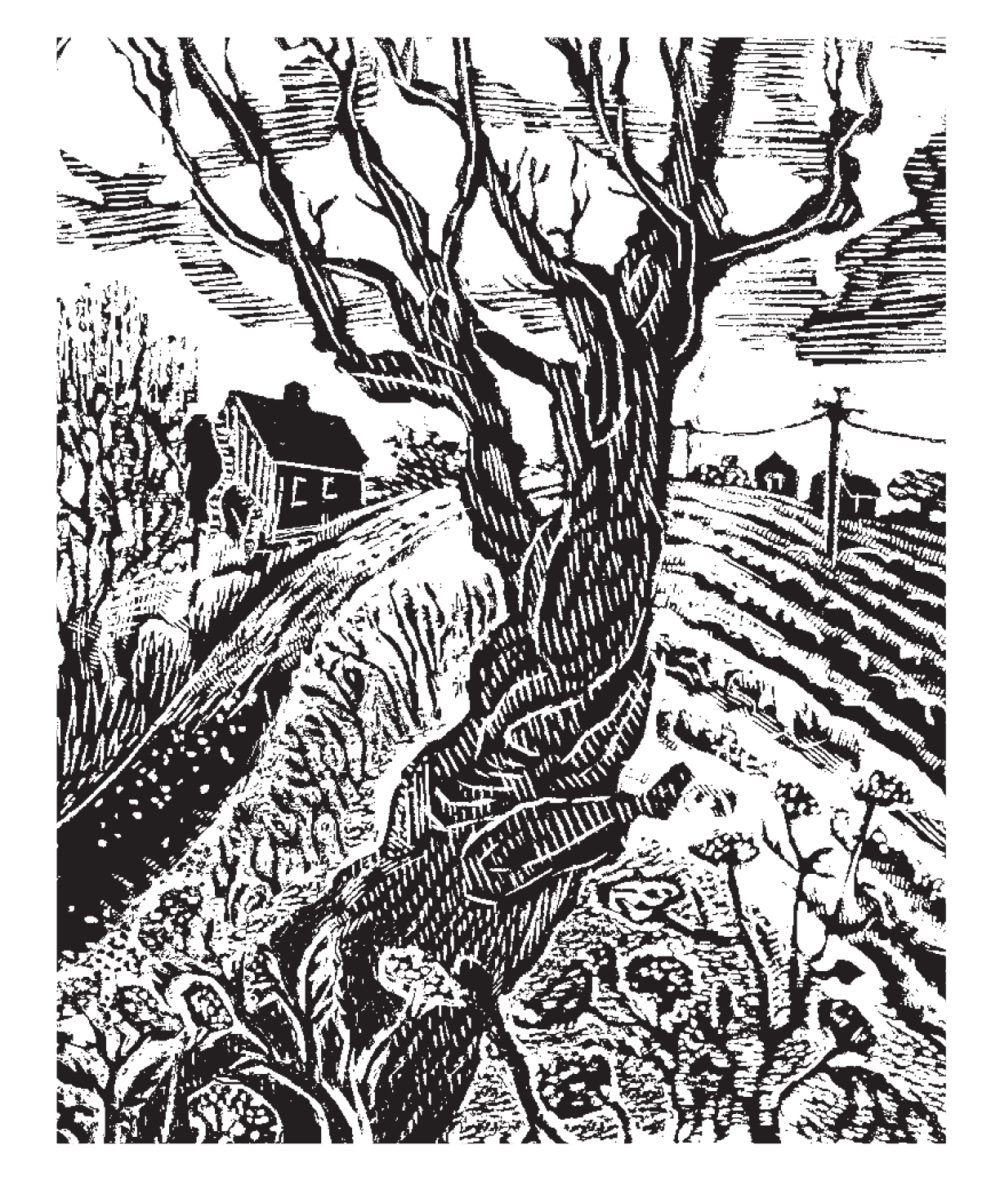

It is now nearly forty years since Ronald Blythe, equipped with a tape recorder and an old Raleigh bicycle, travelled around the Suffolk countryside he had known from boyhood, capturing the memories and reflections of three generations of a rural community, to which he gave the imaginary name ‘Akenfield’ (acen is old English for ‘oak’). These he transcribed, weaving them together with observations in his own precise, poetic prose.

That particular moment in the mid-Sixties provided an extraordinary vantage point from which to look both deep into the past and well into the future. The older villagers – ‘The Survivors’, as Blythe calls them – are steeped in a lore and a way of life that reach back hundreds of years. They talk of the ancient bond between ploughman and horse, and of how they sang to their beasts as they worked the fields. They recall their grandparents hurrying to inform the bees when a villager died, and hanging the hives with black crêpe – ‘if you didn’t, the bees would die as well’. They regret the new prevalence of steel, and the passing of the old method of smelting iron with charcoal to make strong, bright nails such as would have been used at the Crucifixion.

Despite their huge skies and wide horizons, they are a private, circumspect people, and they deliver their memories with a guarded matter-of-factness which occasionally blossoms into poetry. ‘He walked smartly down the lane until his red coat was no bigger than a poppy,’ says one retired farm-worker, recalling his brother’s departure for the Boer War. ‘Then the tree hid him. We never saw him again.’ ‘We dreaded the rain,’ remembers Fred Mitchell, a retired horseman. ‘It washed our few shillings away.’ But the old speech and the old ways were dying fast by the summer of 1967. Farming had become ‘the agricultural industry’, and for those who chose to remain on the land – and many did not – Walls and Birds Eye were the new masters. The gentle, reassuring sounds of ‘larks, clocks, bees, tractor hummings’ are punctuated, as Blythe bicycles about, by automatic bird-scarers exploding across the pea fields like minute guns. The pressure to maximize the return from the land means that animals are no longer allowed to roam on their old pastures, but pass their short lives locked up in sheds. Dr Tim Swift, the vet, speaks chillingly of how boredom and bewilderment are driving battery pigs and hens to cannibalism. The pigs chew off one another’s tails; the poultry go further. ‘First they pick a feather and taste blood, and soon some poor hen is disembowelled. It is a frequent thing.’

Yet Akenfield is not exactly a lament for the past. ‘The Survivors’ describe a turn-of-the-century life of such unremitting toil that nostalgia seems a Marie Antoinette indulgence. Leonard Thompson, aged 71, tells how his father, a farm labourer, brought up ten children on 13s a week. They were always hungry, and almost always thirsty. The nearest drinking water was at the foot of a hill a mile’s walk away. He describes trying to slake his thirst one hot afternoon by swigging down the soapy water in which his mother had just done the week’s washing. Every minute that he was not at school, he and his siblings were required to help with stone-picking in the fields. As soon as he left school, at 13, he took a job with a local farmer singling mangolds: sixty hours’ work each week, for 3s. ‘I want to say this simply as a fact,’ Thompson states, ‘that village people in Suffolk in my day were worked to death.’

In 1914, with two other boys from the village, he fled the wretchedness of rural life for the army, and was sent to the Dardanelles. On the shore, as they landed, was a huge marquee. It reminded them of the annual village fête, so they rushed towards it. Inside were hundreds of dead Englishmen, laid out in rows, their eyes wide open. ‘I thought of Suffolk,’ Thompson comments, ‘and it seemed a happy place for the first time.’

Happiness, Akenfield illustrates, is relative, and rare. By the mid-Sixties, Akenfield is the kind of place weary urban dwellers dream of, with all the emblems of the English village idyll: ‘A tall old church on the hillside, a pub selling the local brew, a pretty stream, a football pitch, a handsome square vicarage with a cedar of Lebanon shading it, a school with jars of tadpoles in the window . . .’ Yet for all their ‘modern’ comforts – fitted carpets, central heating, deep-freezes, cars – most of the younger inhabitants of the village betray an unease quite unknown to their forefathers in the days of semi-feudal toil.

Some yearn for the past. Christopher Falconer, a gardener, spent the first fourteen years of his working life in service to Lord and Lady Covehithe in the big house on the borders of the village. He describes a set-up of Through the Looking Glass oddness, in which the indoor staff were required to turn their faces to the wall when their employers passed, and ‘her Ladyship’ would appear out of nowhere when he was at work in the garden and shout ‘Swing your arms!’ ‘We gave, they took,’ he states. ‘It was the complete arrangement.’ Yet, now that it is gone, he mourns it: ‘I am a young man who has got stuck in the old ways. I am thirty-nine and I am a Victorian gardener, and this is why the world is strange to me.’

Others are overcome with anxiety about the future, unable to shake off the twentieth-century compulsion to ‘get on’: 19-year-old Brian Newton has dreamed from boyhood of working on a farm, but now that he is doing so, he frets. What will he be doing when he is 30? Or even 40? The older men working with him tell him that they didn’t think like this – ‘But I must. At the moment I can’t see any climb or development however hard I work. If I stay I am already where I shall always be.’

Even in those for whom the present appears to be prosperous and full of promise, there is angst. Gregory Gladwell, the blacksmith, has managed to survive the great transition from horse to tractor which spelt ruin for most forges. Newcomers to the village, prepared to spend extortionate sums ‘re-garnishing’ their houses and recreating ‘original’ fireplaces, troop to him with orders for weather-vanes, copper canopies, firedogs, firebacks, brass and pewter ornaments, light-brackets. He is overwhelmed not just with work, but with a nagging guilt about the uses to which he is putting his craft. Is he breaking faith with ‘the old ones’, his ancestors who shod the old farmhorses and made ploughs ‘in the seventeen-somethings – and on this very floor?’ ‘I wasn’t born soon enough,’ Gladwell reflects, ‘that’s the trouble. By rights, I should be dead and gone. I think like the old people.’

When, half way through the book, we are introduced to Horry Rose, the saddler, and told that he is a ‘happy man’, it comes as something of a shock. Can it be so? Is anybody really happy?

Amidst this cast, Blythe maintains a discreet but sharp-eyed presence, able to evoke in two or three brisk brushstrokes a place, a situation or a character. When, for example, he introduces Marian Carter-Edwardes, 50, Samaritan, JP, Vice-Chairman of the Women’s Institute – ‘Surrounded by large dogs and good furniture. Nothing too much trouble. Racy, nothing could surprise her. Good-looking and moves with a girlish, tennis-court freedom. Drives a fast car with dogs looking out of the windows’ – we know immediately what we are dealing with.

Blythe can be wry, but he is also unfailingly sensitive, and he is at his very best dealing with the more vulnerable members of the community, those living friendless and on the fringes. Michael Poole works in the Akenfield orchards. At 37, he cannot read or write a single letter. ‘Simple’ is how local people describe him, emphasizing the word in such a way as to make it clear that he is in no way frightening. But ‘simple’, Blythe explains, ‘is exactly what he is not . . . There is no rest in that “simple” face, it has the alertness of a forest creature, eyes seizing at every object.’ Lana Webb, 23, is incontinent, and lives, unvisited by the other villagers, with her Gran. Their cottage is spotless – the lino ‘translucent, like sucked toffee, its pattern all licked off by the duster’. After Blythe has sat with them for some time, they agree to show him their secret. A door is opened to reveal a long, white room, with the windows open and the wind hurtling through. ‘It is blowing some twenty pairs of knickers. Pink, white, blue, flowered, plain, nylon, cotton, they jig happily above a galvanised zinc bath in which sheets are steeping. Gran closes the door and Lana, her expression faintly amused and challenging now, rises from her chair and goes off somewhere to change.’

Most movingly of all, in the final pages, we are introduced to ‘Tender’ Russ, the gravedigger. A widower, living alone with two budgies, ‘Boy’ and ‘Girl’, he inveighs so wildly against God and man, and against the uncertainties of life, that the other villagers give him a wide berth. His garden is a metaphor for the futility of his rages – ‘Rows of sprouts have rotted until they have become yellow pustulate sticks; potatoes have reached up as far as they could go and fallen back into faded tangles’. In his cottage, he has retreated into one cluttered room. Only among the dead does he feel at ease. He keeps the names of all those he has buried in an address book, and meticulous records of where and how they lie. But for himself he wants no such comforts: ‘I want to be cremated and my ashes thrown in the air. Straight from the flames to the winds, and let that be that.’

Returning to Akenfield fifteen years on, it is the balance between observation and compassion, epitomized in the meeting with ‘Tender’ Russ but running throughout the book, that makes it so memorable, and so moving. Blythe’s aim, as set out in the introduction, was to capture ‘the voice of Akenfield, Suffolk, as it sounded during the summer and autumn of 1967’. But he has achieved something more than this. As the final pieces of his mosaic are put into place, the village becomes a microcosm of the whole world, and one is left with feelings of tenderness, perplexity, wonder, not just for the inhabitants of a small corner of East Anglia, caught at a particular moment, but for the human condition.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 11 © Maggie Fergusson 2006

About the contributor

Maggie Fergusson is Secretary to the Royal Society of Literature. Her first book, George Mackay Brown: The Life, was published in April 2006.