Ronald Blythe (1922–2023)

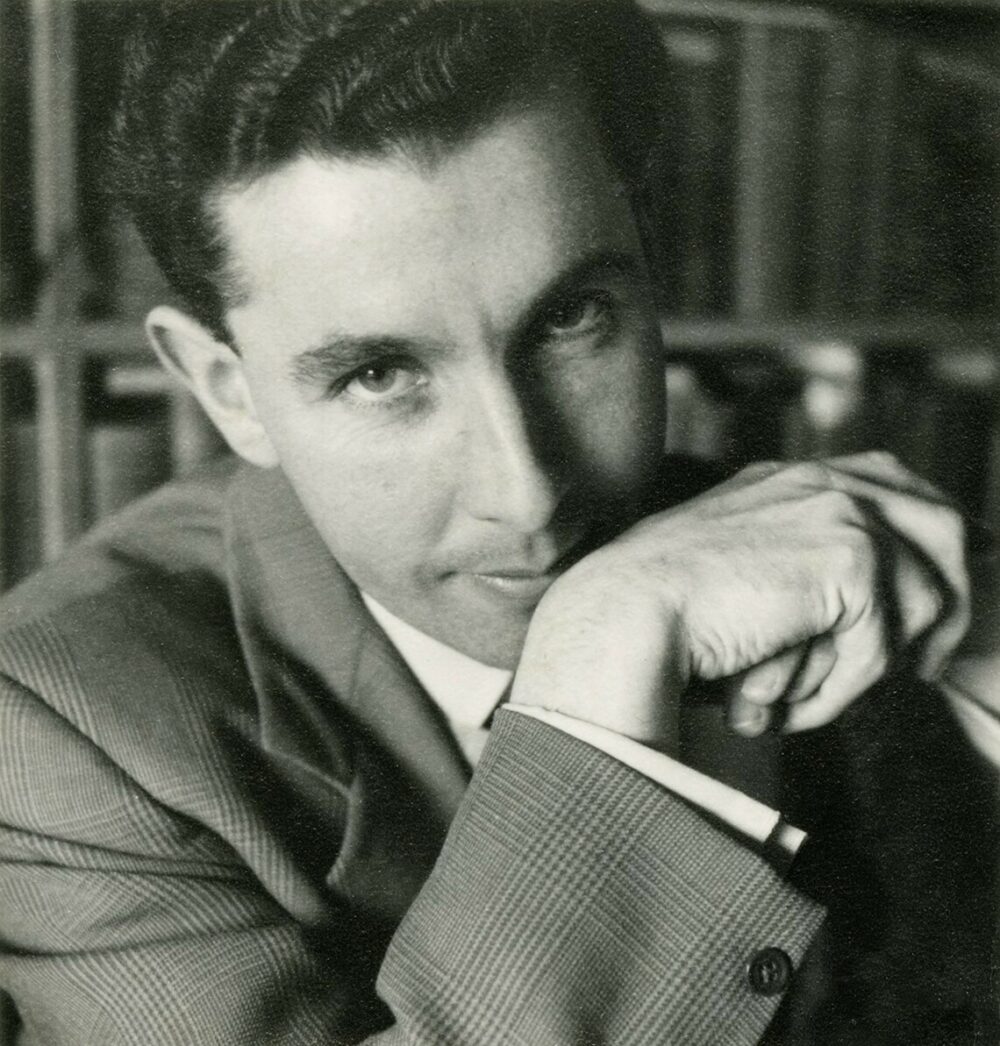

I’ll begin with a description of him. Whenever I sat facing Ronnie at his elegant little table in the corner of the room, close to the crammed bookcases, I was always startled by the way his face changed. At one moment I saw a fragile man growing older year by year and in the next I saw a boy, filled with the laughter and energy of youth.

And now a little story which says something of his approach to life and to people. I was having lunch with him at his house, the wonderfully named Bottengoms. He’d recently been to see a friend who was dying. As a gift he chose the most expensive bar of soap he could find. Guerlain. ‘She’ll enjoy washing her hands, day by day,’ he said. ‘She’s not got long to live.’

It’s odd how one gets to know someone better, or at least in more detail, after they have gone. Ronnie was often in my mind ever since I first met him in 1991, but it’s only now that I begin to see him in his entirety, as it were.

I watched a film made when he was in his 50s. The slight figure of a man with a shock of hair and very narrow hips, walking through the familiar streets of Aldeburgh and talking as he walks. ‘So many friends have died,’ he says, ‘but I have no sense of elegy. They are living because I am living. That must be it.’

And now he is living because we are living.

Last week I went back to Bottengoms, getting lost on the way as I always do and suddenly there was the big wooden post box with no name written on it and the anonymous, sandy and potholed track leading down and up and down again towards the house. You approach it across the garden with its perfect balance of the wild and the cultivated and here is the white painted front door to be pushed open.

The old house which had been his home, his island, since 1977. The paintings. The many books. The beautiful and precarious furniture that once belonged to John and Christine Nash – a flimsy multi-legged table looking as if it would collapse in a heap if you burdened it with the slightest touch . . . A bit of the ceiling bursting open to reveal a patch of wattle and daub, threatening to drop on your head . . . The tangle of copper heating pipes of which Ronnie was so proud that he insisted they ran above the mantelpiece like works of art.

But it was the floor that was most familiar and most moving. The wonderfully higgledy piggledy pale brick floor that you sometimes still find in old churches: each brick a slightly different colour and height and no cement to hold them steady – and, with any luck a family of Great Crested newts, sleeping peacefully somewhere underneath the layer of damp sand.

The first time I met Ronnie, we looked at the worn threshold to his house and at the floor, alive with the energy of time and he quoted a line from a Thomas Hardy poem, ‘Here the dead feet walked in’.

Before we started I was talking to Ian Collins and he reminded me that on his very last day, Ronnie asked to be lifted to his feet, his bare feet, and then he stood on those bricks to feel them. It’s such a wonderful last gesture of being.

We often sat and talked. He spoke of whatever he was currently working on, and he spoke about his friends, both the living and the no longer living, often telling vivid little stories about them that made me feel I knew them too. He was always a generous and enthusiastic critic of my books when they were still in manuscript form and he imbued me with a courage that I will always be grateful for. Of course he did the same for many other writers.

Usually I came for lunch and left after tea, but once I stayed overnight, the two of us in our pyjamas taking turns to brush our teeth at the little sink before retiring, me to a memorably lumpy horsehair mattress.

In spite of our many conversations, I realize now that he hardly ever spoke of himself, apart from the occasional drift of nostalgia for what he felt he had missed in life, even though he did not explain quite what that was. He never once mentioned his childhood.

Ronnie was the eldest of six siblings – all of them sleeping together in the one room. One night when it was very cold, his father fetched a big bundle of straw and scattered it over his children, to keep them warm like piglets in a barn.

His father was a farm labourer. Later he went up in the world and became a gravedigger. His mother had been born into the even more dire inner city poverty of Covent Garden and it seems that she and her husband had little in common. He was a drinker and a shouter, while she was a devout and teetotal Christian. There were no books in the house apart from the King James Bible, but she read those musical cadences, to her children from an early age and they became the foundation of Ronnie’s appreciation of the immense power of the Word.

He left school age fourteen and got a job in Colchester Library where he could devour as many books as he liked. You could say his early years were a disadvantage, but in a way they were the making of him. He did not study authors, he met them and they became his friends and never mind if they had died two thousand years ago or took a cup of tea with him only last week.

The poet John Clare was his greatest love. They shared a knowledge of poverty and a loneliness of being and Ronnie always referred to him with such an easy intimacy, it was as if he was talking about his favourite brother, albeit one who did not have the same good fortune. Clare ended his troubled life in the Madhouse, whereas Ronnie found peace and contentment and a sense of belonging, in the sanctuary that was Bottengoms.

If you look at the early photographs – and the later ones, right up to the party celebrating his one hundredth birthday – you can see why people were so drawn to him. As a young man he was as beautiful as a rather fragile matinee idol and throughout his life he had a quality of openness and innocence and a way of trusting the path of his own destiny, which was very attractive.

Christine Nash met him in the Library and recognized something in him at once. She took him under her clever and wise wing and he became like the son that she and John Nash had lost. He was welcomed into the circle of their friends who were quick to appreciate his particular charm and intelligence. He was charming, but he also had a steely determination. He wrote as if his life depended on it and once he had begun that task, he never relinquished it.

Nine years ago I went to see Ronnie after the death of someone I had loved. I was seeking comfort, but to my surprise he apologised and said he could not be much help: he had never loved anyone deeply enough to have experienced the real, heart-breaking grief of loss.

At first I was shocked, but later I realized that what he said was not only honest, it was also a clue to his nature. He was, in the very roots of his being, a solitary man. He loved everything and everyone with an equal passion. He loved the moon moving through the night sky; the first light of the dawn; the natural world in all its complexity. He loved landscapes and churches for the stories they held and told. And he loved people, all of them, equally, honestly and generously and yet with a certain detachment. Maybe that was the source of the nostalgia for what he felt he had missed.

Ronnie seemed to get younger as he got older. He celebrated his 100th birthday with a glass or two or three of sherry, and a cake made as a copy of his last book Next to Nature and I heard he was delighted to be told that 10,000 copies had already been sold, although he quickly forgot the fact. He let go of life not many days after the party, taking his leave with a quiet acceptance and an easy joy.

He is of course best known for Akenfield; a wonderful and often shocking book that speaks so eloquently of a way of life that had evolved out of the landscape he was born into; a long tradition of rural poverty that was harsh and romantic and on the brink of vanishing; but I do wonder if his most recent writing is his greatest achievement. Like the 16th century essayist Michel Montaigne, Ronnie had become able to follow the meanderings of his own thoughts as they moved from what he had for breakfast, to what Seneca said on hearing of his death sentence, to the cat, to the Holy Ghost, to a walk in the dark.

Like Montaigne, Ronnie was not afraid of dying and I think he would have understood his own death, in the words of John Clare’s poem ‘I Am!’. I remember him reading it to me at our first meeting.

I long for scenes where man hath never trod

A place where woman never smiled or wept

There to abide with my Creator, God,

And sleep as I in childhood sweetly slept,

Untroubling and untroubled where I lie

The grass below – above the vaulted sky.

Julia Blackburn’s eulogy for Ronald Blythe

Given at St Edmundsbury Cathedral, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk

1 March 2023

Ronald Blythe’s dear friend, Ian Collins, generously shared with us a number of wonderful images from Ronnie’s life. The photographs have been kindly provided by Christopher Matthews, David Holt, Meriel Sparkes and Anthony Stamp, with additions from the personal collection of Ronald Blythe, Kurt Hutten (Report/IFL), Anthea Sieveking, Fay Godwin, Jane Garrett and Ursula Hamilton-Paterson.