When I was about 9 or 10, my great passions in life were dogs, football, books, my grandparents’ farm, and a young man who lived in the house next door. I found him impossibly glamorous. He was seven years my senior, he went to pubs, he wore a leather jacket, he had daringly short black hair and sported an earring, he smoked, and he radiated a carelessness and confidence that I hoped might rub off on me – an awkward, shy, slight boy, ridiculously grave and perpetually worried, whose only notable similarity to his neighbour was that he shared his name: he was known as ‘Big Matt’, I was ‘Little Matt’. Still, he noticed me. He would talk to me about school and offer me spectacularly inappropriate advice about girls. He would play me records and make me compilation tapes. He would take me to play football and furnish me with the shirts of his favourite (and hence my favourite) club. Big Matt, it was said, could do no wrong. Until, one day, Big Matt broke Little Matt’s heart.

I can still see the expression, the lined concern, on my father’s face as he prepared to tell me the news. ‘No,’ I said, and cut off his attempt to repeat himself with a desperate restatement of my position: ‘NO!’ There followed a bewildering sense of incomprehension. How could Big Matt be leaving? How could Big Matt be leaving for another country? How could Big Matt be leaving for another country to take up a post in the army? All colour drained from my world.

When Big Matt did eventually leave, three indecently short weeks after my father broke the news of his departure, I took refuge in the company of my dog: we would brood together, walk together, read together, we would daydream together about what Big Matt might be up to. After a while I started to inflict my curiosity on my father. ‘Dad? What do you think Big Matt’s doing?’ ‘Dad? What’s it like being in the army?’ ‘Dad? What are wars like?’ In time my questions got a bit more sophisticated: ‘Dad? Why do we have an army?’ ‘Dad? How long have we had an army?’ ‘Dad? How many wars has Britain fought?’ ‘Dad? Are armies what make history?’ My father coped with my questions patiently, but I am sure he had at least one eye on his sanity when one day after work he said: ‘There’s a book on the table you might be interested in . . .’

I didn’t pick it up straight away but eventually I did settle down with it: Escape from France, by Ronald Welch . . .

I read it in two enraptured sittings. I loved Richard Carey, the hero of the novel: his charm and glamour reminded me of Big Matt, but he was thrilling on his own terms, too. And the action of the book, which takes place in the midst of the French Revolution, was equally seductive and electrifying. Bless my dad: I didn’t need to ask for the other books in the series. He would notice I had finished one and return with volume after volume, leaving each on the kitchen table with barely a word. Before long I had acquainted myself with the entire history of the members of the Carey family, from their activities in Knight Crusader, set during the Third Crusade, all the way up to Nicholas Carey, which ends in the Crimean War.

Revisiting the Carey novels today, I am struck by how fresh and magnetizing they have remained, and by how much there is in these books – as there is in all good children’s literature – that can be enjoyed by adults. It is common for readers of Welch to credit him with sparking a love of history (I know an Oxford scholar of medieval literature who says she owes her career to Welch); what we hear less often is how subtle and careful his use of history can be. Escape from France and Nicholas Carey work brilliantly as historical fiction because the history with which they are suffused is always given a human face.

History, here, is about people, and in focusing on people, these books remind us just how haphazard the evolution of the past can be: how events are determined not just by policies and ‘the subtly laid schemes of statesmen’, as another great historical novelist, George MacDonald Fraser, has his Flashman tell us, but ‘by someone’s having a bellyache, or not sleeping well, or a sailor getting drunk, or some aristocratic harlot waggling her backside’.

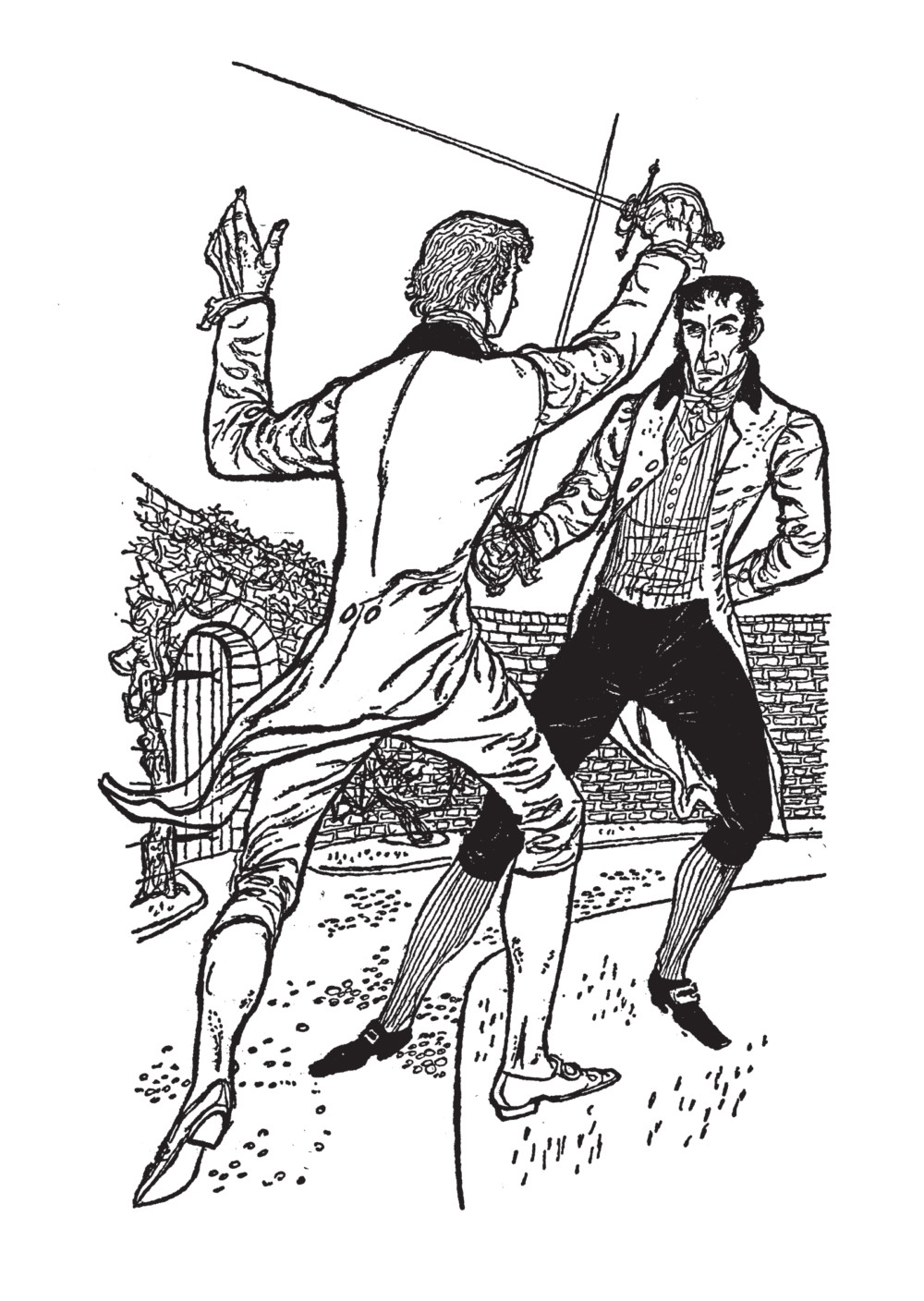

In both Escape from France and Nicholas Carey, much of the action is driven not by events but by accidents of character, reputation, social and familial connection: it is the ‘unwritten rule, that a Carey helped a Carey’, that comes to the rescue of the Emperor of France in Nicholas Carey, just as in Escape from France the safety of Quentin d’Assailly (head of the French side of the Carey family) depends not on Richard’s conscious application, but on his natural resilience and stoicism, and his unwitting brilliance as a swordsman.

When Welch does introduce the reader to major historical events or major historical figures, he tends to do so from the perspective of the street, so that both his heroes and his readers encounter them with the same kind of fleeting immediacy that an ordinary person of the period might have done. Here is Richard Carey, in the heart of Paris in the middle of the French Revolution:

Then he heard a different sound, the clip-clop of many hooves, and a squadron of cavalry trotted past; the crowds swayed and pushed, and fell silent. Richard craned his head out of the window. But there was little to see, except the dense masses of horsemen, and in the centre a large green coach that rumbled swiftly over the cobbles. Richard caught a brief glimpse of a brown-coated man inside, a calm, white face and a high forehead, and King Louis had passed.

This is just one instance of Welch’s remarkable understanding of restraint. How magical to find ourselves on the streets of Paris, afforded only a glimpse of the passing Louis; how tawdry a more prolonged encounter would be.

I remember feeling the frisson of this brush with history when I first read the book. Yet what appealed to me most at the time, and part of what I find most admirable now, is the human sensibility of these stories: what they have to say about what it is to be somebody who feels ill-equipped for the world, who feels he or she has no natural place, who feels forever on the brink of being found out – a perpetual Little Matt. Both Richard and Nicholas Carey are troubled by these emotions; Nicholas suffers particularly acutely. In the novel that bears his name, which begins in Italy in 1853 and concludes in the Crimea in 1855, Nicholas is presented as an officer in the army who has never seen combat; an artist with ‘a liking for solitude’ who has never exerted himself at anything. He feels lazy, and without a vestige of ambition. His childhood, we learn, had been a somewhat lonely one.

Yet as the novel progresses, we begin to see these feelings of insecurity and ineptitude subside. Thrust into a world of action, Nicholas begins to grow up. Not because he has decided to, but because the world has awakened in him qualities that were always there, and he finds himself filled with the exhilaration of a man who suddenly discovers he can lead.

This is the message that recurs throughout these wonderful nov els: that we are invariably better equipped than we believe ourselves to be. There may always be a part of us that feels, as Richard Carey does, ‘a mere child, a beginner, a sheer amateur’, assailed by the sense that we are in ‘the middle of a dream where you try to run, and your arms and legs refuse to move’. Yet in tandem with this truth, Welch reminds us that we are also, all of us, potentially remarkable beings, all deserving of admiration and affection, all capable of that which we fear is beyond us – all capable, in fact, of noticing the talents of ourselves and others, of venturing forth into the world, and becoming our own Big Matts.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 47 © Matthew Adams 2015

About the contributor

Matthew Adams writes and reviews for a number of publications, including the Spectator, the Literary Review, the Independent and the Guardian. He still feels he is on the verge of being found out – but he doesn’t let that stop him. He is working on a novel.